What do those carvings on old gravestones mean?

An independent folklorist tells (and shows) us!

IN THE "SPECIAL PAGE" ARCHIVES:

Simon Clark

Brent Monahan

Joe McKinney

John Shirley

Bentley Little

David Brin

Bill Hinzman by John Russo

Earl Hamner

ARTISTRY FOR THE DEAD: GRAVEYARD SYMBOLISM

By Gary R. Varner

Perhaps some of our most mysterious, impressive and artistic symbolism can be found in our cemeteries. Ancient pagan, classical Greek and Roman, and the eternal symbols of hope, love and despair appear in many of our older places of rest. Unfortunately, with the gradual demise of the hand carved headstone, which has been replaced by the flat, two-dimensional and plain metal plate, these ancient and mystical representations are becoming harder to find.

Researcher Douglas Keister noted that the majority of American cemetery architectural motifs can be divided into six categories:

1. Ancient pagan architecture

2. Egyptian architecture

3. Classical architecture

4. Gothic architecture

5. Late nineteenth and early twentieth century architecture, and

6. “Uniquely funerary architecture.”

Late nineteenth and early twentieth century architectural styles include Art Nouveau, Art Deco and modern classicism.

Humankind has marked the graves of its loved ones for hundreds of thousands of years. In many examples they were marked by upright stones, stone circles, dolmen or complex burial chambers. In others, images of beasts and monsters or the symbols of metaphor adorned the stone markers—and these have carried over into contemporary times. That is until very recently. Today it is more common to find flat slabs of unadorned granite or metal with only the name, birth date and date of death engraved to mark the final resting place of the body. It would appear that money and the lack of the stonemason’s talent has reduced our markers to a purpose that is more utilitarian than as a loving piece of art hand carved for the mourning family.

Like those anonymous sculptures of the gargoyle and grotesque, the craftsmen that created these exquisite carvings on old headstones utilized both approved religious themes and those of an ancient pagan past. “Much of the sculpture’s work,” wrote Potok, “is startling in its mastery; some of it goes beyond craft into the subtler realm of art. Variation and prodigality of symbolism and decoration abound, as if they were entirely without fear of condemnation for idolatry.”

However, what about those strange carvings of dragons and other mythical beasts that are found on tombstones around the world and among diverse cultures of differing religions? “Dragons, monkeys and griffins,” writes Chaim Potok on images found in Jewish cemeteries, “seemed to emanate from some primal apocalyptic bestiary.” Dragons have long been equated with the Devil in Christian lore, the supreme leader of the enemies of God. In other lands, however, the dragon “represents the highest spiritual power, strength, and supernatural wisdom.”

.jpg)

It is not uncommon for various symbolic representations to have the most opposite of meanings between cultures. Christianity is expected to find evil and the Devil in symbols that were, and still are, important among cultures of other faiths and ages as positive images.

St. John used the dragon, as a representation of Satan, in the New Testament chapter of Revelation: “And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angles were cast out with him.”

Griffins too suffer from this duality of meaning. Griffins have appeared in ancient art from Babylon to Greece, Rome and the Orient as a symbol of the sun and the guardian of treasures. The griffin symbolized dominion over the land and the sky and was used symbolically as a sign of power. In the East, the Griffin was symbolic of wisdom and enlightenment—just as the dragon. But, alas, in Christian tradition the griffin depicts evil. The image was used as a symbol of Satan flying away with the souls of those who persecute Christians, or, as Evans relates, demons that “flew aloft on the pinions of pride and fell from heaven into the abyss of hell for their misdeeds.”

Sometime in the 14th century, the griffin became a symbol of the dual nature of Christ rather than the evil of Satan. As is often the case with Christian symbolism, the griffin in its aspect as master of the heavens and the earth was absorbed in Christian iconography and eventually symbolized the Pope as head of spiritual and temporal power.

One of the most common symbols in 16th and 17th century graveyards in the United States is the skull. The skull is the most literal symbol of death. During the 16th and early 17th century Puritan influence dominated and was extremely dark and foreboding in its message. Many markers were adorned with grim skulls and often the wording “Here lies buried the body of…” indicating that the individual lived and died with nothing important between or after.

After Puritan influence began to wane in the mid-1700’s the markers still depicted skulls but skulls with a brighter and more innocent image:

Many of the symbols found on burial markers have even more obscure meanings and origins. Hands are one of the most common images found in pre-twentieth century cemeteries.

The hand pointing up acts as a road sign, telling visitors to this grave that the occupant no longer resides on the earth but has gone onward to heaven.

While hand images are common elsewhere, a hand pointing up appears only in Christian cemeteries.

A similar symbol is a hand with the index finger pointing down which represents God reaching down for the soul, as seen below:

Hands carved on Jewish headstones are shown with the fingers separated “to form openings through which the blessed Shekhinah (radiance of God) streams down upon the congregants.”

Other hand motifs include hands that appear to be shaking. This normally represents matrimony if the sleeves shown appear to be masculine and feminine. If the sleeves are gender neutral the image may be that of a heavenly welcome or an earthly farewell. In Chinese symbolism, clasped hands represent friendliness and allegiance.

The dove is another common figure that has been used to decorate headstones. Perhaps the most common animal figure used in cemeteries, the dove is most frequently depicted as holding an olive branch in its beak. The meaning, of course, refers to the flood myth and the dove that Noah released which returned with an olive branch signifying that the flood waters had receded from the earth. The dove also signifies purity and peace. The symbol of the dove with an olive branch is universally representative of peace.

The dove is an appropriate symbol for burial markers as it also represents “the passing from one state or world to another.”

Across time, the sacred dove has been associated with funerary cults and was sacred to all Mother Goddesses, depicting femininity and maternity.

A double-headed dove, much like the double-headed eagle, signifies the dual nature of unity. The double-headed dove appears to be part of an older Masonic emblem which time has effectively erased. This symbol represents the dual nature of unity and is also an imperial emblem of power and protection. According to the Association for Gravestone Studies, it also symbolizes a 32nd or 33rd degree Mason. An example of a double-headed dove is below:

Other common symbolic motifs on grave markers include various forms of vegetation—both mythical forms and common species. As unlikely as it may seem, a sheaf of wheat is a popular Masonic symbol and is used on grave markers to indicate “someone who has lived a long and fruitful life of more than seventy years.” Other interpretations include the “divine harvest at life’s end” and a life fulfilled.

Wheat is symbolic of immortality and resurrection. Being a staple of life, wheat has been thought of as being a gift from God. Like other cereal crops such as corn and barley, wheat symbolizes the fertility of the earth, renewal, rebirth and abundance. In Christian symbolism, wheat represents the body of Christ, the righteous and the godly.

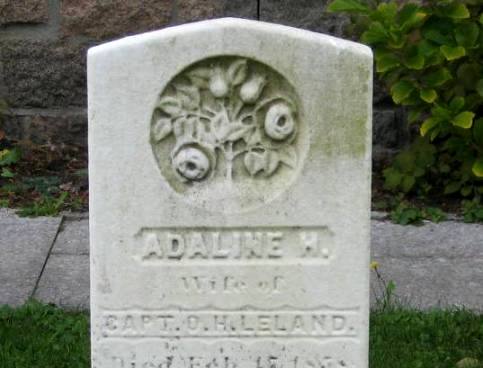

Flowers are often found in cemeteries not only as fresh offerings to departed members of the family or to friends but as carved images on headstones. Flowers are important symbols in many cultures, representing gods and goddesses, the soul and the spiritual flowering of the spirit, immortality and the brevity of life, and of course, rebirth. During the Festival of Rosalia in ancient Rome, roses were scattered over graves.

The rose has, as many symbols do, a dual nature. It has represented “heavily perfection as well as earthly passion.” It also symbolizes both life and death, immortality and the limits of Time. As used in association with funeral traditions, the rose symbolizes eternal life and resurrection. In Christian lore, the rose grows on the Tree of Life, signifying regeneration and eternal life. An example of a rose on a headstone is below:

Palm trees are rather rare as a graveyard symbol but they do occur. In the Mediterranean the palm was long regarded as sacred with the sun god Assure often depicted above the palm. The ancient Egyptians, Romans and Christians were fond of the palm as representative signs of victory both in war and over death. It also represented rebirth.

I recently visited a 300-year-old graveyard associated with St. Helena’s Episcopal Church in Beaufort, South Carolina. Originally established in 1712, the graveyard contains the remains of British troops killed when they attempted to take nearby Port Royal in the Revolutionary War, Civil War dead from the Battle of Port Royal and those who died in all the other 300 years of its existence. One grave is that of Capt. Paul Hamilton who at his death at 20 years of age had participated in 80 Civil War battles for the Confederate States.

Here is Capt. Paul Hamilton's marker that clearly shows a palm tree:

His marker not only has a palm tree carving representing victory over death, but continues to receive scalloped shells left at the foot of his marker as offerings to represent his journey through death and rebirth.

The shell represents a journey and regeneration or rebirth. And is one of the more unusual graveyard decorations—normally it is the scallop shell. Symbolically, the shell represents a pilgrimage or journey however it has also been used to symbolize baptism and fertility.

During the Victorian age, and its associated neo-pagan revivalist motif, other interesting pieces of symbolic art found themselves incorporated in cemeteries as well as on secular architecture.

One of these items is the stone ball. Keister wrote that stone balls in cemeteries are “almost always purely decorative.” A cluster of three such stone balls, however, connotes a gift or money. However, there are other meanings behind this symbol as well. Cooper notes that balls may represent either the sun or the moon and symbolic of the power of the gods to hurl comets from the heavens. Carved stone balls have appeared in widely diverse areas of the world and apparently represent mystic and archaic meanings. According to the Association for Gravestone Studies, these balls may represent the endlessness of time, or eternity, which would be very appropriate for cemetery symbolism.

Victorian influence also was responsible for the introduction of ancient Egyptian motifs into secular architecture and graveyard decoration. The “rebirth” of ancient architectural styles during the neo-pagan revivalist period resulted in some of the more interesting changes to American homes and buildings. This style also came to be used on the tombs of our more wealthy citizenry, who, according to some researchers, did not know the ancient symbolic meaning the image but chose the design due to the popularity of anything Egyptian.

Many of the headstones in our cemeteries also commonly show fraternal symbols. The Masons, also known as the Free Masons, have left their symbols throughout American burial grounds. The primary symbol used is that of the square and the compass, normally shown with a “G” inside the symbol. According to Keister, the square, or carpenter’s square, and the compass represents the interaction between mind and matter, or rather “the progression from the material to the intellectual to the spiritual.” Below is an example:

Biedermann elaborates on this, stating that the square, as it indicates a right angle, stands for what is right, justice and the true law. The compass symbolizes the ideal circle of “all-embracing love” for humanity. The “G” which is centrally located in the image either stands for Geometry or God—or both. The exact meaning is clouded by the organizations reluctance to define their symbols and their meanings.

Other meaningful graveyard symbols include the obvious symbols of patriotism, loyalty and political association. The flag is perhaps the most meaningful and obvious symbol which not only identifies the deceased with his homeland and participation in certain wars but with regional and philosophical values as well. National cemeteries are stark reminders of what we value and what we give up for those values.

Finally our heroes often have significant or historical events depicted on their monuments—not often based on reality but on National Mythology. George Washington is often depicted in full uniform next to God in heaven or armed with the angels to fight evil.

In parting all I can say is that I love cemeteries. They have their own allure filled with history, with the images that were important to or defined the individual. These are placed where people were buried 100, 200 or 300 years in the past and sums up the entire history of our nation—both the heroic times and our times of shame. While not artistic in their form, at times simple words are the most profound.

See other cemetery art HERE

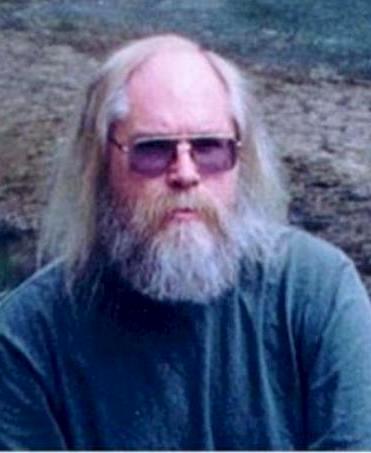

About Gary R. Varner

Gary R. Varner is an independent folklorist who also has a background in archaeology and anthropology. A member of various sections of the American Folklore Society, he has over twenty books in print on such diverse subjects as the Green Man, witchcraft, the Owens Valley Paiute, sacred sites, rock art, cultural diffusion and a cultural history of Ethiopia. He has traveled extensively to research and photograph the subjects he writes about.

References and resources:

Keister, Douglas. Stories in Stone: A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography. New York: MJF Books 2004, 13.

Potok, Chaim. “Forword” in Graven Images: Graphic Motifs of the Jewish Gravestone by Arnold Schwartzman. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1993, 14.

Potok, op cit., 13.

Keister, op cit, 93

Revelation 12:9, King James Version

Evans, E. P. Animal Symbolism in Ecclesiastical Architecture. London: W. Heinemann 1896, 39.Schwartzman, Arnold. Graven Images: Graphic Motifs of the Jewish Grave Stone. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1993, 22.

Cooper, J.C. An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols. London: Thames and Hudson 1978, 54.

AGS Field Guide No. 8: Symbolism in the Carvings on Gravestones. Greenfield: The Association for Gravestone Studies (AGS) 2003, 5.

Keister, op cit., 60.

AGS, op cit., 7.

Cooper, op cit.,141.

Keister, op cit., 110.

Cooper, op cit., 17.

Keister, op cit.,191.

Biedermann, Hans. Dictionary of Symbols: Cultural Icons & The Meanings Behind Them. New York: Meridian 1994, 321.