This Month's Special Page is a Tribute to Author John Gilmore who passed away on October 13, 2016. Learn about John HERE

John tells us all about Hollywood's dark side

....and the stars in it

IN THE "SPECIAL PAGE" ARCHIVES:

Brent Monahan

Joe R. Lansdale

Owen King

Dacre Stoker

Piers Anthony

Simon Clark

Lisa Morton

An article from someone who knew Elizabeth Short

and Marilyn Monroe personally

by John Gilmore

They called her the Black Dahlia the year before she was tortured, murdered and cut in half. Her name was Elizabeth Short, and I’d see Elizabeth in my dreams: she’d come in and out of my dreams like a song you keep hearing after its long-finished playing, just kind of floats around in your head. Since I’d never be able to marry her because she was dead, I remember squatting before my grandmother’s upright Underwood, typing a vow: I swore to whatever unseen spirit hovering over me that I’d never forget her or the kiss she gave me, no matter that I was only eleven years old.

But what could I do about the secret? I still had to keep it. My grandmother made me cross my heart and hope to die if I mentioned to my father that the murdered girl had visited the house that October afternoon just days before Halloween. She came accompanied by two guys, both gay-blade movie extras and friends of a boarder. Elizabeth was dressed all in black, a black veil from her black-feathered hat, cheeks rouged but her skin almost white as chalk. She wore very sheer black stockings, a stark seam down the backs of her legs, and high-heels with open toes showing the red nail polish through the dark nylon.

As though it was yesterday, I can see her standing by the dining room table, flexing her fingers in those black kid-leather gloves that went half up her arms, asking my grandmother about a cousin named Adel Short—something like that—a cousin she was trying to find. Half of the family on my grandmother’s sister’s side had produced a swarm of Shorts populating what seemed like half of Los Angeles.

My grandmother didn’t think she knew the girl Elizabeth was trying to get in contact with, and I remember my grandmother on the phone, calling her sister. “Adeline Short?” my grandmother asked. One of the Short girls, but no one named Adel—or whatever it was.

Elizabeth glanced at me as I stood by the dining room cabinets, actually admiring her, and she gave a smile that probably made me blush. Bright red lips, and her pale blue eyes seemed bright as lights. She was the prettiest lady I’d seen—even better looking than some of the movie extra girls often hanging around.

There were always movie people around because my step-grandfather was a head carpenter at RKO. Although my mother was never around because she’d been divorced from my father since I was six months old, my dad was a frustrated actor who instead become an important Los Angeles police officer. Even Adeline Short was pretty, and so were sisters Gladys and Sally who were blonde, but Elizabeth had a movie star sort of look, and told my grandmother she’d come to Hollywood to work in pictures. My grandmother mentioned that I’d done some radio work as well as giving a magic show. Elizabeth seemed impressed and I invited her to see the magic posters in my bedroom.

I showed her ones of famous magicians I’d seen performing at the Shrine Auditorium, like the great Harry Blackstone who’d made someone disappear right on the stage next to him. “Magic is fascinating,” I remember Elizabeth saying. “It lives in the shadows… It must be a thrill to know you can make somebody disappear right in front of your eyes…”

She told me she wanted to be an actress, but not just an “ordinary actress.” She said it was in her heart to become a star. I recall her saying, “That is the only thing that will make me happy.”

Smiling, she asked if I had ever seen a Barbara La Marr film? I hadn’t. She told me La Marr had been a silent screen star, and Elizabeth said she’d been told she looked like her. La Marr had died years ago, but very young, and Elizabeth said, “My birthday is almost the almost the same date as Barbara La Marr’s birthday,” though a number of years before Elizabeth’s own birth.

She sat on the edge of the bed and I showed her the little printed flyers for my few amateur magic performances. I showed her pictures taken of me in a police safety film made by my father’s LAPD group, and told her I too wanted to be an actor and be in the movies. I said my mother, who lived a couple blocks away, had worked in movies at MGM, and wanted to be a star. I remember Elizabeth’s soft, understanding laugh, and I could see her teeth.

I can still see her teeth. That was some sixty-five years ago, and I can still see her teeth.

She said something about having to find her cousin, stood up as if to gather herself and the black handbag that looked like braided material. She said, “Well, maybe we’ll all be movie stars,” and then leaned forward and kissed me on the forehead. It was like a gentle arrow going into my brain. They drove off in an old Packard, her in the backseat. She raised her hand to wave goodbye to me on the porch, but it wasn’t really a wave—she just placed the palm of her black-gloved hand on the glass.

Two and a half months later, her naked body was found in a vacant lot, gouged, cut in half at the waist, the two halves of her corpse displayed face up, legs spread.

My father and his partner in their black-and-white radio car, circled the vacant, weed-ridden blocks, then went on foot, going house to house, asking if anyone had seen anything strange or unusual, or had they heard any screams in the night?

I’d never said anything to my father about the girl visiting the house. He lived in an apartment behind my grandmother’s house with his second wife—someone I did not like—so for years I said nothing about the murdered girl, but upon my grandmother’s death, I told him. “That girl known as the Black Dahlia,” I said, “the victim in what the newspapers used to call L.A’s most sensational murder—yet to be solved… She was here at the house, but my grandmother asked me not to mention it.”

My father said he understood. See, he already knew. The movie-extra friends of the boarder who had brought her to assist in locating her relative had told him about her visit.

Those two guys have long since vanished or died. I look back to the photo slides of those years and check off all that have disappeared. How many funerals have there been? And still that music circles slowly in my head, but I no longer dream about the suicide bridge in Pasadena, or about Elizabeth approaching me slowly over a hump in the center of the bridge—some hinge that didn’t really exist. I’d be walking towards that hump, in slow motion, getting nowhere. The dream would then crumble, disintegrate like old newspaper falling off a plaster wall.

Most people who’d been vital to me in some way are gone—maybe dead, like Elizabeth had said about disappearing…right in front of your eyes. Way back, I sometimes accompanied my father to dinner at Rudy’s Italian Restaurant on Crenshaw by 39th and Norton. I remember us walking across the boulevard at night, the headlights almost blinding us, then climbing through weeds in the vacant lot where her body had been found. I’d felt hollowed, scared that I’d see her blood on the ground. I didn’t want to see any blood, but there wasn’t blood underfoot. Just every so often there’d be a crunching of the spent, blackened flashbulbs from police and news photographer’s cameras.

The next six or so years, long after Elizabeth’s body was fitted into a coffin and buried in Oakland, her unsolved murder was as cold as when the ice man pushes the big chunk into your ice box. I’d become the young actor—a nightclub hopper from Chasen’s to the Trocadero, to Mocambo and Ciro’s—a potential star dressed white on white, but with empty pockets. I had mentors in Ida Lupino and John Hodiak, and though I’d done some movies and tested at Fox, both mentors suggested I hit out of Hollywood—get a Broadway play and be brought back a success. Hodiak also introduced me to a neighbor, an odd, young angel named Marilyn Monroe, who told me the same thing: “Go to New York.”

I met Marilyn Monroe again one of Wynn Rocamora’s party. He was my agent at the time, a very powerful figure in the industry. Though had a few years on me, both of us had been born in L.A.’s General Hospital Charily Ward, both estranged from family situations, and lonely despite the flash of the fast lane racing past. She was like finding a kindred spirit in a pile of busted wood washed ashore. Marilyn told me that if she had the chance—laughed and said maybe if she had the guts—she’d skedaddle her butt straight to Broadway and land a play.

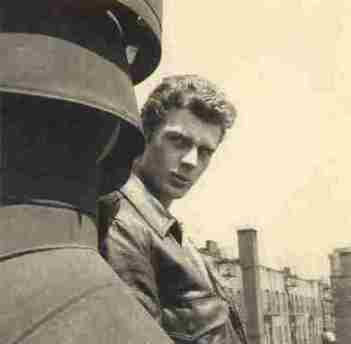

Within a parade of faces back and forth between Hollywood and New York, I found another kindred friend in a young actor named James Dean. We hung out all over New York, and within a year he on his way to Hollywood to make a move that’d shake the city. He’d make two more pictures and then die at twenty-four, racing a sports car half across the desert.

Back in New York, Tennessee Williams told me I should be a writer. He gave me a weird pair of lizard-skin shoes from Cuba that he said hurt his feet. At this same time, Marilyn Monroe was in New York after walking out on a movie. She holed up at the Actors Studio where I was transcribing Lee Strasberg’s obtuse lectures for a book he planned to published.

Marilyn told me the same thing that Tennessee had told me: “You should be a writer,” then followed it with, “I wish I could really write…”

A mutual friend was Susan Strasberg, daughter of Lee, the so-called “guru,” but a failure as a father to Susan. Gore Vidal’s close friend, my theatrical manager. Vidal said the same thing: I should write instead of “waltzing past the footlights.”

After doing theatre and television, I wound up at the Beat Hotel in Paris. William Burroughs introduced me to his publisher who wanted a novel I’d written. I got to know François Sagan—a busy mind, then Brigitte Bardot—busy in other ways.

I went to Egypt on a movie deal—not acting, but writing the script. I met a beautiful Egyptian actress who showed me mummies and monuments, and the back streets of Cairo. The movie became one of many I’d be paid to write—a rollercoaster familiar to many writers: you’re paid but the movie is never made. Their cup doth not runneth over.

Hollywood again and I did TV shows back-to-back, a couple of moves at Fox, then starred in the L.A. production of the William Inge play, A Loss of Roses. Jerry Wald was producing the film—calling it A Woman of Summer. Via William Morris, I was up for a lead opposite Marilyn who was back in the midst of another picture. We’d meet in the back of a tiny coffee shop in Beverly Hills and talk, then have a conference at Fox with Wald and his associate, my good friend Curtis Harrington. Martin Ritt was supposed to direct the movie.

The film ran against into a temporary dead-end the day Marilyn died. She was only thirty-six and disappeared from a drug overdose. Her spirit just vanished. Another friend, Joanne Woodward, did the movie as “homage” to Marilyn, but the production stalled, then revamped and Martin Ritt wasn’t doing it, and I was out of it.

It was the last straw, as they say. You’re almost at the top of the mountain when the landslide hits. I figured that maybe I had better start listening to people’s suggestions about becoming a writer.

I wrote quickie novels to get off the mountain. Didn’t call them fine literature, but I was inside my own head, no longer “waltzing past the footlights.” I’d started working on a big novel set in those Cairo backstreets, when novelist Bernie Wolfe asked me to do legwork for him on a piece for Playboy. A young guy, Charles Schmid, had murdered three girls and buried their bodies in the Arizona desert. They said he’d also murdered a teenage boy cut off his hands and buried him as well. We were on our way to cover the first murder trial—for two of the girls, while Schmid was being held in Pima County Jail. Bernie knew I had ways of worming into people, and said he’d pay for whatever I dig out of Schmid’s friends. He said, “Promise them anything—just get a scoop.”

We flew to Tucson where I wormed into the killer’s pals and a legion of young girls who were Schmid’s “fans.” Many things were told to me in confidence, especially from his almost teenage wife. Their Mexican wedding had come after the murders. So I had to skirt some issues when I laid the stuff out for Wolfe. I told him there were things I couldn’t reveal as I’d sworn silence. I said it wouldn’t have been ethical.

He fired me.

I flew back to Hollywood, scraped up enough to complete the job on my own and caught the next plane back. Schmid, labeled “the pied piper of Tucson” in Life magazine and almost every media in the country, had refused to testify. His trial ended with two death sentences. I’d made inroads into Schmid during the trail, and next was a post-trial meeting at the jail. He was to make me his personal manager and gave me his story on a platter—not blood-stained since his victims were strangled.

Soon as the Pied Piper was sent to sit on Death Row in Arizona State Prison, awaiting murder trial number two, I moved temporarily to Tucson and spent the next two months involved, at the killer’s request, in piecing together his life story—more a task of sorting the fact from the fiction. Again at his request, I brought F. Lee Bailey into the case. Bailey did a lot of fussing over money with Schmid’s parents, but the bucks weren’t to be had. He nonetheless took the case, gave a good show since the body of the third girl had never been found, but bailed out soon as he realized the prosecutor wasn’t the “desert hick” he’d imagined. Bailey saw himself headed nowhere, not a pretty picture, and since Schmid already had two death sentences, a fight wasn’t going to make a whole lot of difference. They’d gas him anyway.

When it was all over, Schmid showed the law where he’d buried the third body—a beautiful teenage girl. He even helped dig up her skeleton. A kind of good will gesture. The rumored fourth body was never found, and Schmid was shanked in prison. Despite being stabbed repeatedly in the chest and head, one thrust directly into an eyeball, it took Schmid ten days to die.

I began on work on the book, slithering and slipping in a legal swamp and a killer’s wild flights of imagination. And then it happened. Tom Neal, star of the noir classic, Detour, called me about the Black Dahlia.

My stomach twittered. She rushed back into my head. He had “a sweet deal,” Tom said, to do a movie with himself as the lead detective on the case, and with connections via my father’s LAPD bigwigs, we’d “cinch it up” and “come out smiling.”

Elizabeth was once again in my life, once more in my dreams. I could smell the same perfume, hear that rustle of her stockings when her legs brushed together. I didn’t like the idea of writing a movie about her, seemed wrong, but once I read the autopsy report that pointed up her inability to bear children or fulfill herself sexually, and after I got to know a couple girls she’d roomed with briefly, the lure to know more drew me in so deep I wondered if I’d ever get out. I just didn’t want it to turn to quicksand.

I liked Tom—he could’ve been truly a big star, along with Barbara Payton. But the heady indulgences between the two somehow birthed a third form like a kind of freak shadow that destroyed them both. She became a wino whore after washing out a $5,000 a week movie contract, though Tom at least began managing a Palm Springs hotel restaurant, and had married a pretty girl with class.

I was way into it with cops and cops’ pals and those living in L.A.’s gopher holes who wouldn’t even give you a name, when Tom got all wired, said it had nothing to do with me or the project, and raced off to shoot his pretty wife in the head with a .45.

Prison, of course. His so-called backer who no longer wanted to make a movie, was a reclusive wacko sitting on three-million bucks in Barstow, California. I visited him. He wanted to touch the bottoms of my feet because I’d walked on the ground where the Black Dahlia’s body had been found. He said, the Black Dahlia murder was a dead issue—an “antique” unsolved that nobody cared about. Nobody’d want to see a movie about Elizabeth Short, and nobody’d read a book about her.

I went on to publish The Tucson Murders by Dial Press in New York, my first major hardcover, following an commitment with another publisher to explore the life and crimes of Charles Manson and his so-called ‘Family.’ That resulted in The Garbage People.

Apart from talking to Manson himself, though crazy as he seemed, and others in the case, it was pin pointedly Susan Atkins who sort of telescoped into the heads of these walking or crawling monsters. Susan was only too eager to talk murder—the bloodier it was the better she liked it. She gave me a sense of true horror the way her eyes glowed, and that slow-motion flickering of a smile as she spoke about of her desire to cut the unborn baby from Sharon Tate’s womb for a barbeque with Charlie.

No sooner was The Garbage People published than Manson’s right-hand killer, Bobby Beausoleil, the handsome ex-star of Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising, contacted me to visit him on San Quentin’s Death Row.

We spent two days skirting the details of the smothering and stabbing murder for which Bobby’d received a death sentence. His strange tale served me to rewrite for a later, updated edition: Manson: The Unholy Trail of Charlie & the Family.

Next, my Hollywood literary agent contracted for a novelized book on the Zodiac murders. It was signed for hardcover but the publisher decided to rush it in paperback. I opted out. I wouldn’t have done if I knew they were going for a mass-market paperback instead of a hardcover. I didn’t return the advance—no waltzing past footlights.

I settled back to work on the Egyptian novel, but my agent had a deal for a memoir on James Dean. A publisher had a book on Dean by another writer, but hadn’t contracted yet. They’d throw that out and do mine because I’d been a friend of his. I didn’t want to write it. I’d never even wanted to talk about Jimmy. But the offer was good: I was married, I had a daughter. I did the book and it sold one-hundred-fifty-six-thousand copies.

The money didn’t sew up a tear in the marriage. We divorced and I realized I had nowhere to go, except to get out of L.A. Head back to New York? San Francisco? Cairo?

I took an apartment briefly behind Grumman’s Chinese theatre, thumbed through offerings from art colonies and decided once again to “Get the Fuck out of Hollywood.” Years would go by before I’d appreciate the stupidity of that point-of-view.

I’d been born and raised in Hollywood, a native son with the bitch goddess forever offering me the sweet nectar of her Jayne Mansfield-like bosom.

It would take a while to go home. In fact, two more marriages, another child—a son, a heavy two year live-in romance with a stand-in Marilyn; a life in Louisiana and gathering all I could about Clyde and Bonnie (her middle name Elizabeth, and like Marilyn and Elizabeth Short, Bonnie could never have children). another life in New Mexico with a third wife and after that divorce, the journey home—to Hollywood, but then to find the love/hate relationship I’d carried for Los Angeles was missing.

I could say to myself I no longer have to say I yearn to be home but there isn’t any home to go to. I am home. Doesn’t matter whatever else, and not to look at all that’s passed in some light other than is bright. The memories are delicious.

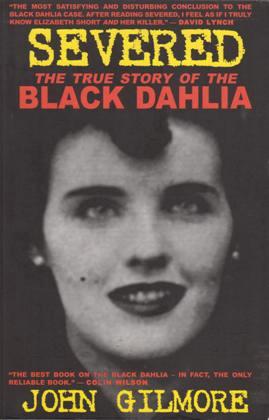

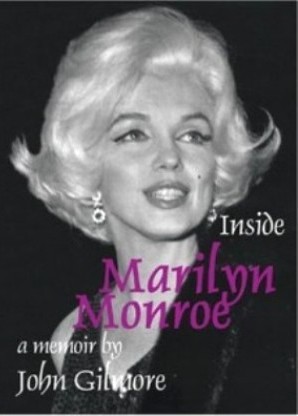

Seventeen years ago I finished my book on Elizabeth: Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia, the first ever book on the real case, about the real person. The hack Bandwagon followed (of course), and since then the world has become decorated with the Black Dahlia. There are many editions of my book, translations, and it has never gone out of print. I do not have an exact count of how many copies have sold. Severed is one of more than a dozen I’ve written, including one I said I’d never write—Inside Marilyn Monroe. Too close to the belt, and so, so radically different from the general mindset on anything “Marilyn.”

Movie star Mamie Van Dorn, who I've known since the late 50’s at Universal, once asked me if I was in love with a dead woman. I was so "locked up with it," said she, the same as she thought about my "forty year silence over Marilyn...after she died.” Mamie said she loved the book I'd written on the Black Dahlia, and then the memoir about Marilyn, but said both were "heavy with implication..." Of course I said no, no, that wasn't it. But I didn't believe myself, and had to ask, if Mamie's wrong, then what was it?

I’m a guest speaker at the Marilyn Memorials, and have been the past four years. The 49th Memorial was August 5th, in Westwood. Next year’s the big one: the 50th. Everybody is coming from everywhere, can you believe that Marilyn will be dead fifty years? I will not be doing any more Memorials after that. My outward participation will have come to an end. So now, it’s back to the Egyptian memoirs, to the mummies and monuments and the backstreets of Cairo…

John Gilmore

Hollywood, California

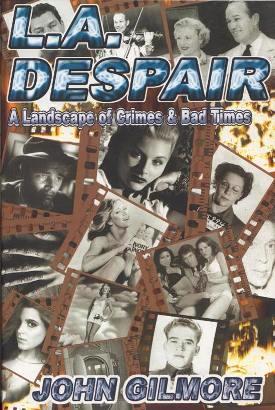

Described by the Sydney Morning Herald as the “quintessential L.A. noir writer,” and “one of America’s most revered noir writers,” John Gilmore has been internationally acclaimed for his hard-boiled true crime books, his literary fiction and Hollywood memoirs. LAID BARE: A Memoir of Wrecked Lives & the Hollywood Death Trip, has been called, “one of the best books ever on Hollywood,” (Marshall Terrill). His memoir, Inside Marilyn Monroe, based on his friendship with the screen legend, candidly reveals her unhappy background and her struggle to the pinnacle of movie stardom, while laying the groundwork for her premature demise.

Gilmore’s following spans the globe from London to Tokyo, from Hong Kong to Hollywood. Son of a former actress, and a Los Angeles police officer father, Gilmore was born in Los Angeles and raised in Hollywood. He has traveled the road to fame in many guises: kid actor, stage and motion picture player, painter, poet, screenwriter, low-budget film director, journalist, true crime writer and literary novelist. He has headed the writing program at Antioch University, and has taught and lectured extensively, having made an incomparable contribution in true crime literature. Married and divorced three times, Gilmore now lives in the Hollywood Hills where he is at work on two more books.

About Mamie Van Dorn (with John above)

John says: Mamie Van Dorn, who I've known since the early days at Universal, once wanted to know if I was in love with a dead woman. I was so "locked up with it," said she, the same as she thought about my "forty year silence over Marilyn...after her death." She loved the book I'd written on the Black Dahlia, and then the memoir about Marilyn, but she said both were "heavy with implication..." Of course I said no, no, that wasn't it. But I didn't believe myself, and had to ask, if Mamie's wrong, then what was it?

Elizabeth Short alive:

Elizabeth short in death:

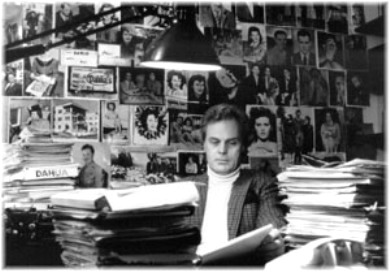

John Gilmore in his acting days:

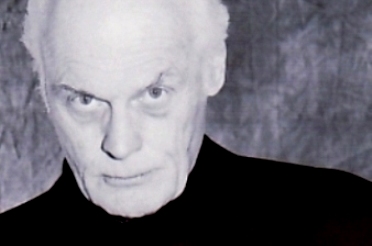

Studio Head Shot of John Gilmore:

John Gilmore researching The Black Dahlia: