On this month's Special Page:

Award-winning British writer Simon Clark gives us five tips on writing

IN THE "SPECIAL PAGE" ARCHIVES:

Dale Kaczmarek

Owl Goingback

Paul Tremblay

Joe R. Lansdale

Ramsey Campbell

John McLoughlin

Ray Garton

Jonathan Maberry

MAKE ME FRIGHTFUL

Five Devilishly Good Tips for Writing Horror as Revealed by Simon Clark

In 1915 Howard Philips Lovecraft sat down in his mother’s home, amid the dark winding streets of Providence, with their ancient Georgian houses peering from swarming thorn bushes. Then he filled a fountain pen with his favourite velvety black Skrip ink and, as a thunderstorm broke over the city, he wrote this sentence: ‘I wish I could write fiction, but it seems almost an impossibility.’

This self-doubter went on to craft some of the most striking fiction of the 20th Century. So what made Lovecraft revise his low opinion of his own literary talent? I suspect he began to examine the likes of Poe, Le Fanu and Blackwood and painstakingly learnt the techniques of the eerie tale, figuring out the ingredients, extracting the secret of how to send a shiver down the reader’s spine. Just like buildings obey the principles of architecture so supernatural horror fiction requires certain rules relating to how the thing is actually constructed. Just two years after Lovecraft voiced his inability to write fiction he produced ‘The Tomb’ and ‘Dagon.’ A little while later he expounded his literary theory in the tones of one who knew, without a shadow of a doubt, what he was talking about: ‘such things as the maintenance of a single mood and achievement of a single impression in a tale, and the rigorous paring down of incidents to such as have a direct bearing on the plot and will figure prominently in the climax.’

Ever since the writing bug got its barbed teeth into me as a teenager and wouldn’t let me go I’ve worked as hard as I could to scrutinize the mechanics of story-telling. In truth though, if the piece caught hold of me I often enjoyed it so much that I forgot I was supposed to be taking notes and underlining passages in books, and had to start all over again. Stephen Kings’ The Shining is one such novel. I revisit certain passages and think, ‘Damn, that’s good.’

Other terrific examples that have me drooling like a vampire in a blood bank are Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan, William Hope Hodgson’s The House on the Borderland and basically everything by Shirley Jackson. It’s tricky to analyse a story when you’re enjoying it so much. As one of my old teacher’s perceptively uttered when I was ten, ‘Simon loves to read, and he does read a lot, but he doesn’t take notice of spelling or punctuation.’ Yup, I was terrible speller. Sorry, Mr. Offord, I’ve tried hard to improve (although I make full use of the spell-checker, too).

So: to cut to the chase. What follows are five tips that should prove useful if you are tempted to write horror. I can’t guarantee commercial success; after all, learning the techniques of horror isn’t like learning the three-times table: there’s no mathematical correct way to calculate the scare ratio of a scene, where, for example, the young widow sees her hanged husband walking up the garden path with the noose around his neck.

Whether this scene chills the reader depends not only on the use of horror elements but inspiration drawn from the depths of the writer’s soul. I think of the combination of ‘inspiration’ and ‘craft’ something like this. Inspiration is the wild river that gushes down the hillside. Craft is the waterwheel that captures and controls (to a certain extent) that chaotic yet powerful flood. It certainly isn’t easy, and if it does come easily I fear that you might not be doing it right. After all, Arthur Machen, one of the greatest exponents of the fantastic ever, sighed regretfully, ‘We dream in fire, yet we work in clay.’

Inspiration without control, or at least a degree of control, will probably result in a block of words on a page that will fail as a coherent story. Lovecraft experienced this early in his writing career. His first short tales were more like recollections of dreams -- okay, they were beautifully written visionary fragments of prose, but they just didn’t make the grade as a fully-fledged story. A reading of ‘The Tree’, ‘The Other Gods’ and other youthful works bear this out. Not that I can add loftily that I knew better than Lovecraft as a young writer. Far, far from it.

My early compositions were twenty-line fragments of ‘feeling’ and part-formed ideas. Just to home in on one particular example, which also turned out to be a break-through piece for me, was when, aged around twenty, I was struck by a story idea. A work day morning, I sat on the bus for my forty-minute journey to the office when, through the rain clouds, I saw a shaft of brilliant sunshine casting a pool of golden light on the fields; it was like a spotlight skating across crops and pasture. For some reason I found myself wondering what kind of person might become obsessed with such a shaft of sunlight and follow it; only for it to continue skating across the countryside for years, so eventually the young man, who chases it, becomes an old silver-beard doggedly following it to the end of his life. These ideas came as a white-hot blast of inspiration.

At the earliest opportunity, I wrote down a great splurge of words, raw sentences, vivid impressions; a welter of uncontrolled passion. What a piece of writing! What exuberant description! What lyrical lines! What a story! Was it hell! To be gracious to my younger self I can describe it as an unusual prose poem. But there was no plot. It was like someone shouting out an account of a potentially interesting incident over a telephone but the recipient only catching odd phrases here and there -- certainly nothing that amounted to a coherent narrative.

A few weeks later, I came across my excited scribblings about the man who followed a shaft of sunlight all his life. Then I applied some self-discipline. I worked out that there was a basis for a ‘real’ story here. One with plot, characters, setting, but it needed hard work to shape it, to make sense of a welter of jumbled impressions.

Eventually, I teased this chaotic jumble into a coherent, if decidedly strange, plot. I liked the idea of the old man’s obsessive pursuit of the light shaft and his belief that there was something magical in its ability to enchant him. He would, I decided, describe his quest to another character. This character would be an ordinary guy who falls overboard in stormy seas. Eventually, he struggles to a rocky outcrop where he encounters a bizarre figure who recounts his life-story as a light chaser. This became ‘A Trip Out For Mr. Harrison’, my first real story. I sent it to a local radio station, they liked it, and bought the broadcast rights for fifteen pounds; I was amazed, elated, vindicated. My first professional sale. It was broadcast to the population of Yorkshire one Sunday lunchtime.

If anything here, I’ve strived to emphasize that knowing how to craft a story is important. Is it more important than natural talent, out-of-the-blue inspiration, artistic impulse?

Well, that’s up for debate. But if this essay helps guide you toward writing stories that sell then I can derive satisfaction from that. Here, I want to focus largely on creating and sustaining atmosphere. We’ll summon the master once more when I quote Lovecraft: ‘Atmosphere is the all-important thing, for the final criterion of authenticity is not the dove-tailing of plot but the creation of a given sensation.’ While not wanting to disagree with a brilliant author I’d suggest that character, plot and craft are important, too. Without further ado here are those five tips:

ATMOSPHERE: Like background music for a film, or its setting, ‘atmosphere’ should be almost a subliminal message to the reader that strange events lie ahead. In fiction ‘atmosphere’ is often conjured from the page by descriptions of place. For example, the sinister look of the house that the honeymooners approach after their car has broken down on a stormy night. Or the forbidding attic room the boy sleeps in at his uncle’s house. Or the gloomy forest the school party are lost in. If you create the right kind of atmosphere then the reader will happily accept whatever baleful monster springs forth in a few pages time.

A wonderfully powerful example can be found in Poe’s ‘A Descent into the Maelstrom’. Instead of Poe glibly announcing ‘a stretch of dangerous coast’ we are confronted with a fabulous vista; this is a monumental riff on what that meeting between ocean and dry land can be: ‘To the right and left, as far as the eye could reach, there lay outstretched, like ramparts of the world, lines of horridly black and beetling cliff, whose character of gloom was but the more forcibly illustrated by the surf which reared high up against it, its white and ghastly crest, howling and shrieking for ever.’ Here cliff and sea become raging monster that has a single mission; to make you its victim -- or at least that’s the subliminal message I get in this powerhouse of writing.

In my own work, I try to evoke feelings of unease, if not downright fear. In Lucifer’s Ark I aimed to prepare the reader for some extremely gruesome scenes by having the character gaze at the ocean. I hope I’ve done two jobs here. Firstly, to provide a description of the place; secondly, to suggest this is the kind of setting where bad things happen: ‘She shivered, and as she peered through the porthole she felt the coldness of that icy world reach into her to lay its deathly fingertips on her heart. The Baltic Sea was little more than a grave - one very large, very sodden, very wet grave. Hundreds of wrecked ships lay on the seabed. Aircraft by the score had plunged into it, never to be seen again.’

This is where I long to add more and more examples from the likes of Blackwood, Shirley Jackson, King, Joel Lane, Mark Samuels… writers who can create and sustain atmosphere … but although an examination of the subject could easily fill a whole book it’s time to move onto:

LOCATION: Where a story is set strongly influences atmosphere, plot and character. One set in the Arctic will evolve along different lines from one in a tropical city even if the plot is largely the same. If you are a new writer here is one tip: Have your story unfold in a place you know very well. Perhaps your old school, your local park or even in your own house. An intimate knowledge of location can make a story really come alive in ways that you couldn’t have anticipated.

THE CRAFT. Musicians perform the work of other composers before they try their hand themselves. Writers are expected to ‘compose’ their own fiction from start of their career. It’s worth taking time to study the craft of the story. Read books on literary theory. Also, one thing I found extremely useful was to pick a story by a great writer then sit down and copy it out. No, I’m not advocating theft here. Copy out the story line by line then put the copy in a drawer. For learning the craft of writing, the balance between description and dialogue, the deployment of techniques, and so on, this will be an invaluable lesson.

MOOD. For me horror fiction has to be serious: no gags, no funny one-liners if the hero falls into a huge lens grinder (‘Oh my gosh, I’ve made a spectacle of myself’ See? It falls short of hilarious anyway). You can have horror-comedy, agreed, especially in films, but in books it tends to be a one-off novelty. Witty one-liners in scenes of high tension are a sure way to deflate the drama.

HELP ME, I’M STUCK! A common problem is the writer hitting an arid patch when the words dry up and they think ‘What happens now?’ The hero has had exciting adventures in the opening pages now he’s back home, had a shower, made some supper but suddenly the plot stops. My tip is the ‘unexpected visitor.’ This could be the arrival of figure at the door. It could be a stranger saying ‘You don’t know me but I have an important message for you.’ Or a brother in need of urgent help. Or a bad guy with a gun. It needn’t be human, of course, it could be a monster. Or even a storm, or an object falling from the sky to crash through the roof. What the ‘unexpected visitor’ does is kick-start a story.

That’s all for now. I hope these are of use to you if you plan to become a horror author, and even if you don’t, these techniques should give you an insight into how a writer works. One thing to remember about the rules of fiction technique is to learn how to use them, and once you have don’t be afraid to break them. As a writer your goal is not only to explore worlds of imagination, but to create them, too. And, to my mind, it’s the best possible job in the world.

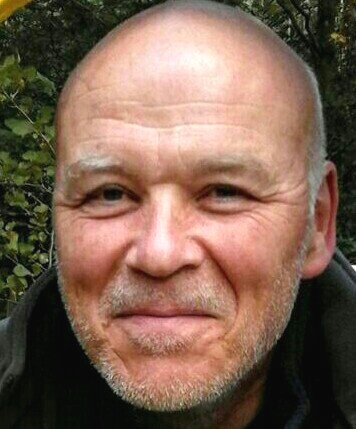

Simon Clark is the author of many novels and short stories, including Blood Crazy, Vampyrrhic, Darkness Demands, Stranger, Bastion and the award-winning The Night of the Triffids: his adaptation of the novel has been broadcast as a five-part drama series by BBC Radio. He has also edited two anthologies of Sherlock Holmes stories for Robinson books, The Mammoth Book of Sherlock Holmes Abroad and Sherlock Holmes' School for Detection.

A short film based on his short story 'The Gravedigger's Tale' can be found on YouTube. Made by Joel Champ, the film has some striking special fx and delivers enjoyable chills aplenty to the spine.

Coming soon from Simon, an eerie Sherlock Holmes novel Lord of Damnation, published by Weird House