On this month's Morbidly Fascinating Page:

Where did the victims of the Titanic disaster end up?

IN THE ARCHIVES:

Time Travel

Mike the Headless Chicken

Disgusting Food Museum

Bat Bombs

Spanish Flu

Pompeii

The Titanic Graveyard

The Fairview Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia houses 121 victims of the Titanic sinking

Fairview Cemetery is a cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia. It is perhaps best-known as the final resting place for over one hundred victims of the sinking of the RMS Titanic. Officially known as Fairview Lawn Cemetery, the non-denominational cemetery is run by the Parks Department of the Halifax Regional Municipality.

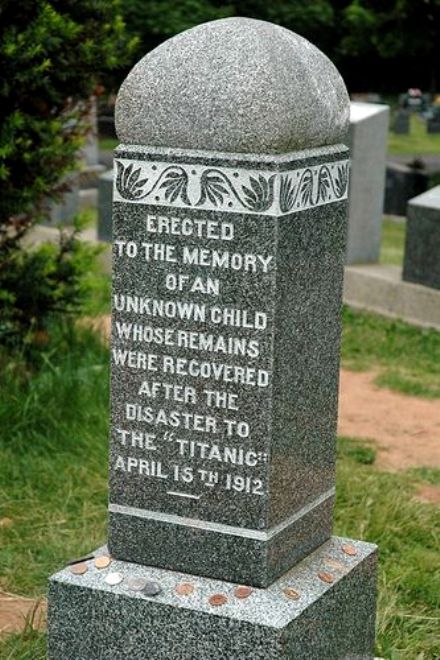

One hundred and twenty-one victims are interred at Fairview, more than any other cemetery in the world. Most of them are memorialized with small gray granite markers with the name and date of death. Some families paid for larger markers with more inscriptions. The occupants of a third of the graves, however, have never been identified and their markers contain just the date of death and marker number.

Surveyor E. W. Christie laid out three long lines of graves in gentle curves following the contours of the sloping site. By co-incidence, the curved shape suggests the outline of the bow of a ship.

When the RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and sank on April 15, 1912, search-and-rescue teams from Halifax, Nova Scotia were sent to assist with recovery. Many of the deceased (mainly crew members and third-class passengers) were laid to rest there following the sinking.

Fair Lawn Cemetery is the final resting place of 121 of these victims. Many of these names have become culturally significant. The most famous of these victims is The Unknown Child, a young boy who identity was a mystery for 90 years.

Graves of Titanic victims can also be found in nearby Mount Olivet and Baron de Hirsh Jewish Cemetery. Halifax is also home to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, whose Titanic exhibit features items including the log of the ship’s wireless messages as well as one of the only surviving deck chairs from the doomed vessel.

See more HERE

Who was the "Unknown Child?"

New DNA evidence and a toddler’s shoe kept in a drawer for decades have solved the mystery of the Unknown Child from the Titanic who lies buried in Halifax.

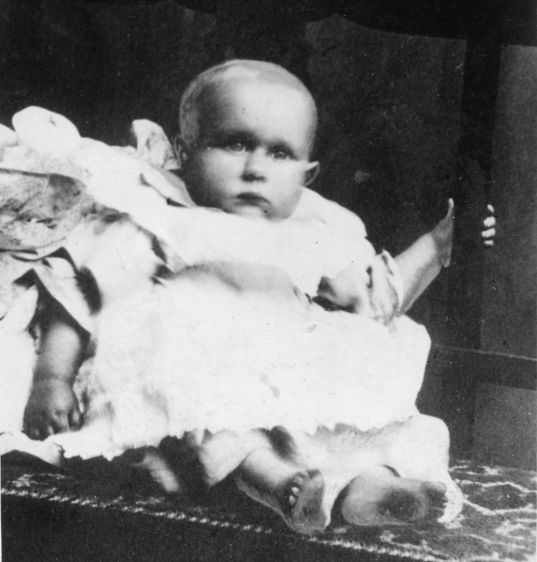

Sidney Leslie Goodwin, 19 months old, drowned when the “unsinkable” ocean liner sank off Newfoundland on April 14, 1912. With him were his mother, father and five older brothers and sisters, all third-class passengers bound for a new life in Niagara Falls, N.Y.

“It was the shoe that tipped it,” genetics researcher Ryan Parr, vice president of Mitomics Inc. in Thunder Bay, told the Staron Wednesday.

Clarence Northover, a Halifax police sergeant in 1912 kept the shoe after helping guard the bodies and clothes of the few recovered Titanic victims. The idea at the time, said Parr, was to burn the clothing to thwart souvenir hunters. But Northover didn't want to burn the tiny shoe, so he put them it in his drawer at the police station.

After his death, his grandson donated it to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax.

An examination of the tiny leather shoe sent the team of American and Canadian researchers back to the mitochondrial DNA samples.

The samples narrowed the choice to Panula and Goodwin. The U.S. Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory in Maryland found another marker that pointed, with 98 per cent certainty, to Goodwin.

The lad’s aunt was Carol Goodwin’s grandmother, and Carol had grown up listening to stories of the Goodwin family perishing on the Titanic.

They had switched to the Titanic from the SS New York after it became possible for the eldest child, 16-year-old Lillian, to join them. They switched to third class from second to save money “and give themselves a faster start when they arrived,” she told the Star from her home in Wisconsin.

A retired child advocate, Goodwin, 77, sees the grave of her first cousin once removed as always representing not just Sidney Leslie but all of the 50 children who died on that voyage.

Sidney’s body, she said, was found floating, without a life-jacket, five days after the liner hit an iceberg. Rescuers were so moved, they decided to bring the body ashore and bury him as a reminder of the children whose bodies they couldn’t recover.

“Grass has never grown around that tombstone,” she said.

See more HERE

Is the marker (below) the resting place for Jack Dawson of the John Carpenter movie fame?

People have flocked to the small headstone for years, leaving flowers and love notes at what they believe is the final resting place of the man who inspired Leonardo DiCaprio’s doomed character, Jack Dawson, in the 1997 film “Titanic.” And you can see why: The inscription reads “J. Dawson died April 15, 1912.”

Not quite, though. While the grave does belong to a victim of the world’s best-known shipwreck, he was not a handsome artist named Jack who won his passage in a poker game, but an engine-room worker named Joseph who probably had little time for onboard dalliances. The producer of the film denies any connection between the crewman and the fictional heartthrob.

DID ANYONE SUE WHITE STAR LINE (TITANIC)?

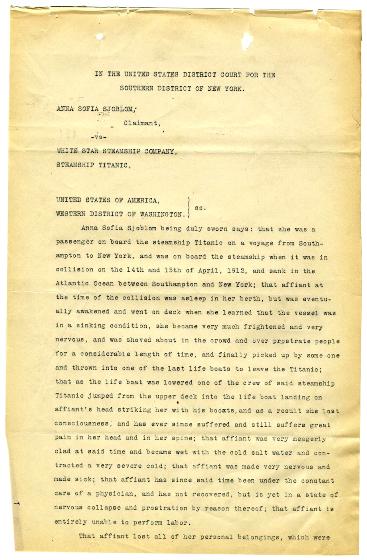

The sinking of the Titanic, on April 15, 1912, was just the beginning of a protracted transatlantic legal battle, in which those who had lost cargo and loved ones when the ship went down sought to get some compensation from the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company (parent company of the White Star Line).

This document, prepared for Titanic passenger Anna Sofia Sjöblom, is one of many claims jointly filed against the ship’s owners by people who made it through the disaster.

Sjöblom, a Finnish immigrant, was bound to Washington State to join her father. She was a third-class passenger on the ship, and spent much of her time during the journey seasick in her bunk. Her claim, which describes her experience of the ship’s sinking, reflects the terror of an eighteen-year-old girl who spoke no English:

She became very much frightened and very nervous, and was shoved about in the crowd and over prostrate people for a considerable length of time, and finally picked up by some one and thrown into one of the last life boats to leave the Titanic.

While this narrow escape might have seemed like a stroke of luck, Sjöblom claimed that a crew member then jumped into the boat and landed on her head, “striking her with his boots,” and as a result she had “ever since suffered and still suffers great pain in her head and in her spine.”

The British owners of the Titanic successfully petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court in 1914 to be allowed to pursue limitation of liability in the American court system. Many of the factors leading to the loss of life on board the ship were judged to have been unforeseeable, or else the damages would have been even higher.

Hundreds of claimants had joined the suit, asking for more than $16 million in damages. In the end, the company paid a total settlement of $664,000 to be divided among them.

While it’s unclear whether Sjöblom received the full $6200 she asked for, she did make it to the Northwest, succeeded in reuniting with her father, and lived to the age of 81.

See more HERE

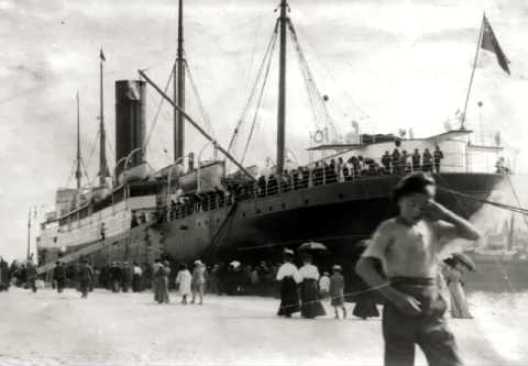

RMS Carpathia at port (below). This ship was first on the scene and was able to rescue over 700 passengers of the Titanic.

History

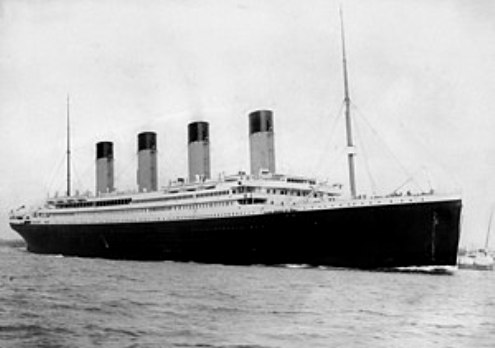

Considered one of the greatest marine disasters in recorded history, the story of RMS Titanic begins in Southampton, England on April 10, 1912, when the vessel left on her maiden voyage. For some of those who lost their lives aboard the ill-fated ship, Halifax, Nova Scotia is where the story ended.

On Sunday, April 14 at 11:40 pm, the Titanic struck a giant iceberg and by 2:20 am on April 15, the “unsinkable ship” was gone. The first vessel to arrive at the scene of the disaster was the Cunard Liner RMS Carpathia and she was able to rescue more than 700 survivors. On Wednesday, April 17, the day before the Carpathia arrived in New York, the White Star Line dispatched the first of four Canadian vessels to look for bodies in the area of the sinking.

On April 17, the Halifax-based Cable Steamer Mackay-Bennett set sail with a minister, an undertaker and a cargo of ice, coffins and canvas bags. She arrived at the site on April 20 and spent five days carrying out her grim task. Her crew was able to recover 306 bodies, 116 of which had to be buried at sea. On April 26, the Mackay-Bennett left for Halifax with 190 bodies. She was relieved by the Minia, also a Halifax-based cable ship.

The Minia had been at sea when the Titanic sank, but returned to Halifax in order to collect the necessary supplies before sailing from the Central Wharf on April 22 for the scene of the disaster. After eight days of searching, the Minia was only able to find 17 bodies, two of which were buried at sea.

On May 6, the Canadian government vessel CGS Montmagny left Halifax and recovered four bodies, one of which was buried at sea. The remaining three victims were brought from Louisbourg, Nova Scotia to Halifax by rail. The fourth and final ship in the recovery effort was the SS Algerine, which sailed from St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador on May 16. The crew of the Algerine found one body, which was shipped to Halifax on the SS Florizel.

The majority of the bodies were unloaded at the Coal or Flagship Wharf on the Halifax waterfront and horse-drawn hearses brought the victims to the temporary morgue in the Mayflower Curling Rink.

Only 59 of the bodies placed in the morgue were shipped out by train to their families. The remaining victims of the Titanic were buried in three Halifax cemeteries between May 3 and June 12. Religious services were held at St. Paul's Church and at the Synagogue on Starr Street. Burial services were held at St. Mary’s Cathedral, Brunswick Street Methodist Church, St. George’s Church and All Saint’s Cathedral.

Various individuals and businesses expressed their sympathy by donating flowers and wreaths. The coffins of the unidentified victims were adorned with bouquets of lilies.

Most of the gravestones, erected in the fall of 1912 and paid for by the White Star Line, are plain granite blocks.

See more HERE