On this month's Morbidly Fascinating Page:

How dinosaurs evolved into modern birds

IN THE ARCHIVES:

Ghosts of Alcatraz

Hansen’s Disease

Accidental Photos

Deaths on Mt. Everest

Titanic Graveyard

Time Travel

How Dinosaurs Shrank and Became Birds

From Scientific American Magazine

Modern birds descended from a group of two-legged dinosaurs known as theropods, whose members include the towering Tyrannosaurus rex and the smaller velociraptors. The theropods most closely related to avians generally weighed between 100 and 500 pounds — giants compared to most modern birds — and they had large snouts, big teeth, and not much between the ears. A velociraptor, for example, had a skull like a coyote’s and a brain roughly the size of a pigeon’s.

For decades, paleontologists’ only fossil link between birds and dinosaurs was archaeopteryx, a hybrid creature with feathered wings but with the teeth and long bony tail of a dinosaur. These animals appeared to have acquired their birdlike features — feathers, wings and flight — in just 10 million years, a mere flash in evolutionary time. “Archaeopteryx seemed to emerge fully fledged with the characteristics of modern birds,” said Michael Benton, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol in England.

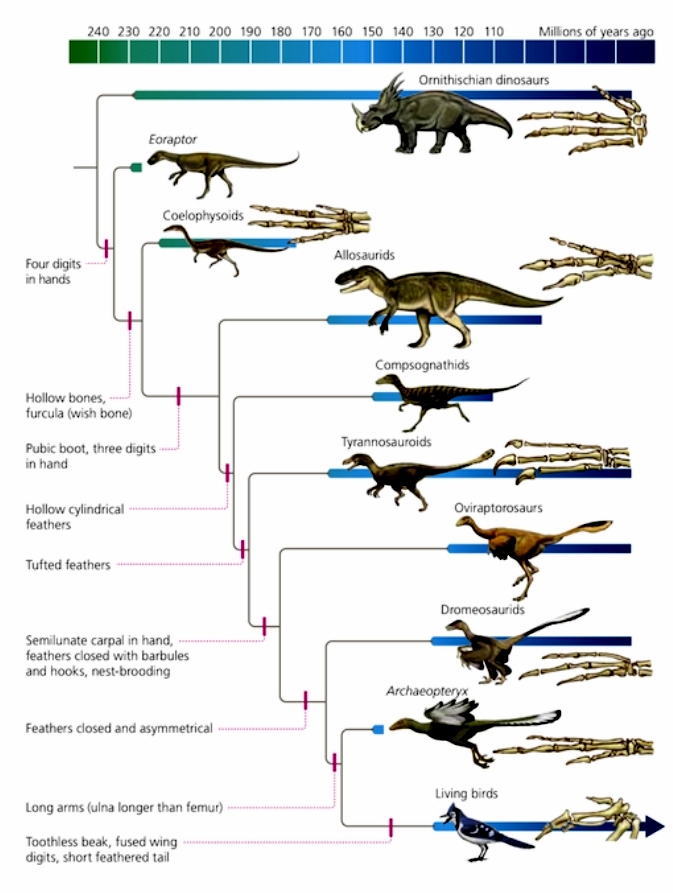

In the 1990s, an influx of new dinosaur fossils from China revealed a feathery surprise. Though many of these fossils lacked wings, they had a panoply of plumage, from fuzzy bristles to fully articulated quills. The discovery of these new intermediary species, which filled in the spotty fossil record, triggered a change in how paleontologists conceived of the dinosaur-to-bird transition. Feathers, once thought unique to birds, must have evolved in dinosaurs long before birds developed.

Sophisticated new analyses of these fossils, which track structural changes and map how the specimens are related to each other, support the idea that avian features evolved over long stretches of time. In research published in Current Biology last fall, Stephen Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, and collaborators examined fossils from coelurosaurs, the subgroup of theropods that produced archaeopteryx and modern birds. They tracked changes in a number of skeletal properties over time and found that there was no great jump that distinguished birds from other coelurosaurs.

“A bird didn’t just evolve from a T. rex overnight, but rather the classic features of birds evolved one by one; first bipedal locomotion, then feathers, then a wishbone, then more complex feathers that look like quill-pen feathers, then wings,” Brusatte said. “The end result is a relatively seamless transition between dinosaurs and birds, so much so that you can’t just draw an easy line between these two groups.”

Yet once those avian features were in place, birds took off. Brusatte’s study of coelurosaurs found that once archaeopteryx and other ancient birds emerged, they began evolving much more rapidly than other dinosaurs. The hopeful monster theory had it almost exactly backwards: A burst of evolution didn’t produce birds. Rather, birds produced a burst of evolution. “It seems like birds had happened upon a very successful new body plan and new type of ecology—flying at small size—and this led to an evolutionary explosion,” Brusatte said.

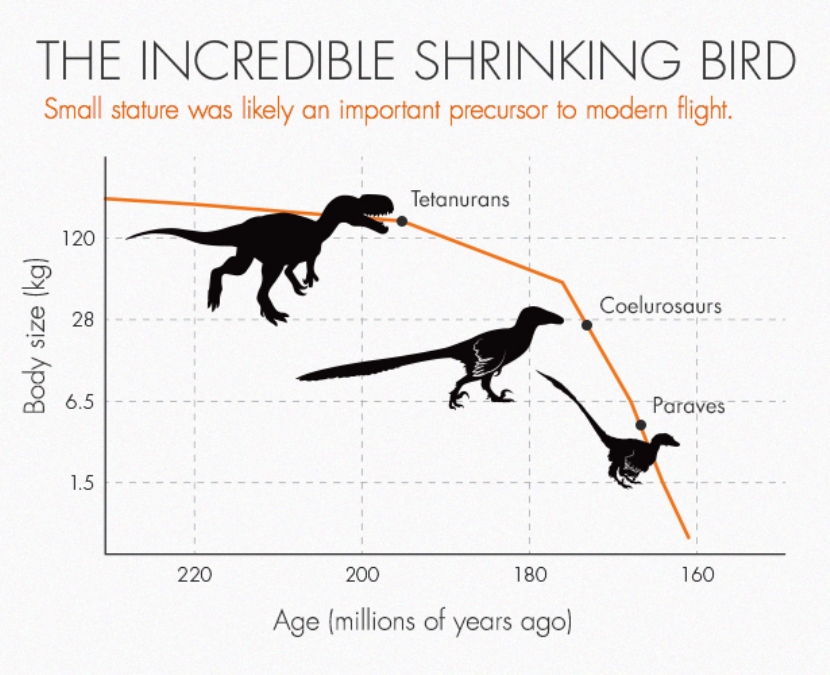

“Miniaturization is unusual, especially among dinosaurs,” Benton said.

That shrinkage sped up once bird ancestors grew wings and began experimenting with gliding flight. Last year, Benton’s team showed that this dinosaur lineage, known as paraves, was shrinking 160 times faster than other dinosaur lineages were growing. “Other dinosaurs were getting bigger and uglier while this line was quietly getting smaller and smaller,” Benton said. “We believe that marked an event of intense selection going on at that point.”

Over time, they discovered, the face collapsed and the eyes, brain and beak grew. “The first birds were almost identical to the late embryo from velociraptors,” Abzhanov said. “Modern birds became even more babylike and change even less from their embryonic form.” In short, birds resemble tiny, infantile dinosaurs that can reproduce.

This process, known as paedomorphosis, is an efficient evolutionary route. “Rather than coming up with something new, it takes something you already have and extends it,” said Nipam Patel, a developmental biologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

See the entire article HERE

What is the first known bird-dinosaur?

Archaeopteryx (whose name means "old wing") is the single most famous transitional form in the fossil record.

The reputation of Archaeopteryx as the first true bird is a bit overblown. True, this animal did possess a coat of feathers, a bird-like beak, and a wishbone, but it also retained a handful of teeth, a long, bony tail, and three claws jutting out from the middle of each of its wings, all of which are extremely reptilian characteristics that are not seen in any modern birds. For these reasons, it's every bit as accurate to call Archaeopteryx a dinosaur as it is to call it a bird. The animal is the perfect example of a "transitional form," one that links its ancestral group to its descendants.

In 1859, Charles Darwin shook the world of science to its foundations with his theory of natural selection, as described in "The Origin of Species." The discovery of Archaeopteryx, clearly a transitional form between dinosaurs and birds, did much to hasten the acceptance of his evolutionary theory, though not everyone was convinced (the noted English curmudgeon Richard Owen was slow to change his views, and modern creationists and fundamentalists continue to dispute the very idea of "transitional forms").

See the entire article HERE

What were pterodactyls?

The dinosaur popularly known as a pterodactyl was a reptile called a pterosaur, which is Greek for flying lizard. It had the "wings" of a bat (a membrane) connected to an extended finger, and no feathers.

Although pterosaurs may often be grouped with dinosaurs in children’s picture books, they were not dinosaurs. “Dinosaurs are characterized by a set of anatomical features pterosaurs don’t have,” explains Mark Norell, the curator of the exhibition and chair of the Division of Paleontology, including a hole in the hip socket.

Today’s scientific consensus is that pterosaurs are nonetheless more closely related to dinosaurs, whose living descendants are birds, than to any other group, including the next-closest, crocodiles.

Are Birds Really Dinosaurs?

Coelurosaurian dinosaurs are thought to be the closest relatives of birds, in fact, birds are considered to be coelurosaurs. This is based on Gauthier's and others' cladistic analyses of the skeletal morphology of these animals. Bones are used because bones are normally the only features preserved in the fossil record. The first birds shared the following major skeletal characteristics with many coelurosaurian dinosaurs (especially those of their own clade, the Maniraptora, which includes Velociraptor):

- Pubis (one of the three bones making up the vertebrate pelvis) shifted from an anterior to a more posterior orientation (see Saurischia), and bearing a small distal "boot".

- Elongated arms and forelimbs and clawed manus (hands).

- Large orbits (eye openings in the skull).

- Flexible wrist with a semi-lunate carpal (wrist bone).

- Hollow, thin-walled bones.

- 3-fingered opposable grasping manus (hand), 4-toed pes (foot); but supported by 3 main toes.

- Reduced, posteriorly stiffened tail.

- Elongated metatarsals (bones of the feet between the ankle and toes).

- S-shaped curved neck.

- Erect, digitgrade (ankle held well off the ground) stance with feet postitioned directly below the body.

- Similar eggshell microstructure.

- Teeth with a constriction between the root and the crown.

- Functional basis for wing power stroke present in arms and pectoral girdle (during motion, the arms were swung down and forward, then up and backwards, describing a "figure-eight" when viewed laterally).

- Expanded pneumatic sinuses in the skull.

- Five or more vertebrae incorporated into the sacrum (hip).

- Straplike scapula (shoulder blade).

- Clavicles (collarbone) fused to form a furcula (wishbone).

- Hingelike ankle joint, with movement mostly restricted to the fore-aft plane.

- Secondary bony palate (nostrils open posteriorly in throat).

- Possibly feathers... this awaits more study. Small, possibly feathered dinosaurs were recently found in China. It appears that many coelurosaurs were cloaked in an external fibrous covering that could be called "protofeathers."

See the entire article HERE