The September Editor's Pick is Christian A. Larsen

Please feel free to email Christian at: christian@exlibrislarsen.com

BAST

by Christian A. Larsen

The fluorescent light flickered like the minds of the residents. Sometimes it lit up the entire breadth and depth of the hallway, and sometimes—most times—it only interrupted the peace of the darkness.

“I hate this place,” muttered Marty, counting off the room numbers. The patients, end-stage dementia sufferers and terminal cancer victims shambling past in flapping terrycloth robes, gave him the absolute willies. They looked like something out of a George Romero movie. He hated the smell worse, though—a mix of piss, disinfectant and ointment that made the nursing home stink like a giant litter box.

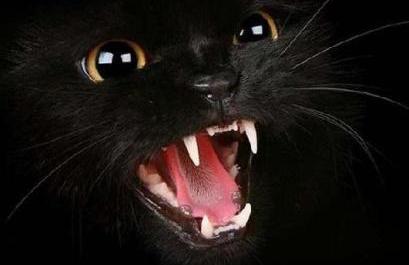

The woman at the nurse’s station smiled when he walked past, but never looked up from her Sudoku game. In fact, the smile never reached her eyes. “Can I help you, sir?” she asked automatically, scrawling numbers in a grid without pausing for an answer. A fat black cat lifted its head from a porcelain bowl where it had fallen asleep. It followed Marty with its good eye. The other was sewn shut and made it look like it was winking at him.

Marty mumbled a perfunctory no thanks to the nurse and shuffled into his grandmother’s room. The sun was a sinking tangerine and the lights were off, but he could hear her breathing raggedly—a faint snore repeating through her diminished frame.

“Grandma?” he asked and wondered why. He hadn’t had a real conversation with her in weeks. Not since a couple of months after she checked into the home, since the beginning of her great inexplicable—but not totally unexpected—geriatric decline.

“Hubert? Is that you? It's too bright. I can’t see.”

“Grandma, it’s me. Marty,” he answered, drawing a chair closer to her bed. With the faint purple coming in through the windows, he could see the outline of her face like a silhouette portrait cut from black construction paper.

“They were having a party outside, Hubert.”

“Who was?”

“The people in the white coats.”

“The doctors? Where? Out in the hall?”

“No, the people in the white coats were having a party, Hubert. Don’t you listen?”

Marty didn't know why he was bothering with the conversation, given that she thought he was his years-dead grandfather Hubert, but at least they were connecting, at least a little, and it might be for the last time, too. At least he hoped it might be. “Where was the party?”

“Across the river,” she sounded angry.

“Didn’t they invite you?”

“No, they wouldn’t stop inviting me!”

For a long time, he couldn’t draw anything else intelligible out of her. She moaned and groaned about the cat trying to kill her, how she was afraid to swim, that she wasn’t ready, and why did she have to go in the first place? Marty patted her hand. Her skin felt thin and loose, like it was ready to slide off of her bones in a pile, and it made him shiver. Willpower. Old-fashioned German bull-headed willpower. That was the only thing holding her together.

The doctors had said she had six months left in her, tops. That was thirteen months ago, and it beat Marty up every time he came back to see her, a little less there than the last time. But enough of her was left to fight that inevitable slide. How he wished that part of her was the first to go. He didn’t mind seeing her bruised from the IV lines, or feeding her a cafeteria version of Thanksgiving dinner. What he minded was seeing her living through these nightmares like they were real, and waking up meant dying. Maybe she would be better off really dying.

Marty slumped back in the chair and watched the sunlight drain from the twilight. His grandmother was sleeping, or some variant of it, but he told her about his day, anyway. The mundanities, the trivialities about his job, how his wife was handling grad school courses—whatever came to his mind. It was reflexive. He didn’t actually intend any of it. It merely came out as the room fell into nighttime, with only the flickering fluorescent trapezoid cut by the doorway casting any light.

Something brushed up against Marty’s leg and he reached down in that momentary panic—where the small unknown seems life-threatening—and barely missed the fluff of the cat’s tail. It sprang onto his grandmother’s bed, settled between her feet, and looked at Marty with its single, slitted, radioactive eye.

“Shoo, puss. Go on, go,” said Marty, waving his hands at the animal. It looked back at him with something akin to bemusement. “I said go!” he repeated, reaching for the cat. It hissed at him and bared its teeth. When it reared back, the light from the door caught a white splotch on its chest shaped like a swinging noose.

Marty settled back into his seat. It wasn’t doing him any harm. Yet. But then it started to crawl up toward his grandmother’s face, the blades of its shoulders pistoning higher than its sleek black head. Marty looked over his shoulder toward the nurse’s station.

“Can someone come in here and get this cat?”

When he turned back, the cat had settled on his grandmother's chest, where it proceeded to lick its paws. There was a faint wheezing noise coming from the bed, like a broken motor or an air-hose leaking from a pinhole. The sound drew Marty forward, and for a couple of seconds, he thought it might be the cat purring, but it wasn’t. The sound was coming from higher up, and then it shaped itself into words in his grandmother’s voice.

“I c-c-can’t breathe, Hube-b-b-bert-uhh.”

“Grandma!” shouted Marty, reaching for the cat with both hands. It stood its ground and glowered at him with its one chartreuse eye. Marty tried to pick it up, but it seemed to weigh more than a thousand pounds. It let out a long purr that sounded like a burp.

Then the room went quiet.

“Grandma? Grandma?” whispered Marty, suddenly and surprisingly very afraid that she might be dead when just a few minutes before he had hoped as much. He took her hand in his and he patted it. It felt cold. He fumbled around her wrist and couldn’t feel a pulse. “Nurse!”

“What’s the problem, sir?” asked the nurse sleepily as she entered the room.

“My grandma’s not breathing and I can’t get this cat off her chest!”

As he was saying that, the cat jumped off the bed and padded past Marty with its tail sticking straight up, flashing its anus at him. In the oddly cast shadows, the animal looked bigger than a small dog. The nurse called the staff physician and he declared Marty’s grandmother dead a few minutes later. “I’m sorry, Mr. Gustafson,” the doctor offered.

“Doctor, there was a cat in here…”

“That’s Bast, a shelter cat. She’s a favorite around here. Named after the Egyptian cat goddess.”

Marty didn’t know why any of that was important when they should have been talking about his grandmother. “Why does that cat have the run of the place? That cat sat on my grandmother’s chest.”

“Bast snuggles up to people when she’s feeling affectionate, and the residents seem to like her. She brings their spirits up.”

“You didn’t hear me. That cat, doctor, sat on my grandmother’s chest and squeezed the air out of her.”

“Now, Mr. Gustafson, I’ll admit she’s overfed, but old Bastie doesn’t weigh more than twenty-five pounds, give or take. She doesn’t weigh enough to do what you described. Besides, if you were so concerned, why didn’t you just pick her up?”

“I tried. I couldn’t move it.”

“I understand,” said the doctor. “Some people don’t like cats. I’ll talk to the director of the home about keeping the cat out of places she’s not welcome. And again, I’m very sorry for your loss. We’ll make the arrangements for you.”

Marty felt like arguing, but let it go because of the offer of arrangements. Still, he felt like pointing out that he didn’t have feelings about cats one way or the other—at least cats in general. But this Bast he didn’t like at all, from its one-eyed glare to the noose on its chest, to the way it squashed the tidal breath out of his grandmother’s dying body. Still, he was too numb to take it any further, so instead he worked with the home about the arrangements for his grandmother’s body, and afterward, he walked back down the flickering hallway. Most of the residents were asleep this time, but Marty still had the willies for some reason.

“Well, Grandma, I guess you won’t have to be afraid of being alone in the dark anymore,” Marty said out loud, feeling like he was whistling past a cemetery. He signed out at the visitor’s check-in, spun himself through the revolving door and out of that litter box smell.

But the outside didn't smell any better. Marty supposed it was either on his clothes or up both nostrils, and he’d have to shower when he got home. Hell, he needed a shower anyway, but it would have to wait until after he walked Freya. She was wagging her tail in the backseat. He waved at her with his free hand as felt the door handle catch with the other.

It was in that last split second that she growled and bared her teeth, too late to be an effective warning. He thought—as quickly as only such thoughts can be—how odd she looked, and then something hit him like the sweet spot of a baseball bat, right between the shoulder blades and knocked him down to the pavement.

The dog was going nuts inside the car, a million miles away. There was a terrible weight on his back and another noise, breathing just above his ear, the hissing of a cat. He felt it curl its claws between his shoulder blades and start to press the air out of his lungs, just like he’d watched it do to his grandmother, and he couldn’t even gather the breath to shout for help. His eyesight was graying out, and the last thing he would ever see was his bald tires. I guess I didn’t need that alignment after all, Marty thought.

Freya, though, tested the door with her weight and it gave. Marty heard her scramble out, her claws and jaws snapping and scrambling onto the pavement. Marty felt her weight on his legs and hips, but even for a dog her size, it was reassuring. The cat hissed and dug its claws deeper into Marty’s back—this time a move not of predation, but of desperation. One cat paw moved off of Marty’s back and Freya whimpered, drawing back. Marty’s hopes went up in smoke. The cat got Freya. There goes my last chance.

But he was wrong again. Freya leaped back, snapped at Bast, got a hold of something, and pushed her weight against Marty’s side, peeling the cat off of his back. Bast mewled pitifully, raked its claws across Marty’s back, and then was gone. He managed to look up. Freya’s teeth were red with cat blood, her lips curled in a feral snarl.

Marty dragged himself off the pavement and sat against the side of the car. “Good girl, Freya. Good dog.” Freya dropped Bast’s wrung and punctured corpse in front of Marty and sat down, panting like her master. Marty reached up and scratched the deep pile under the dog’s throat. His arms trembled, a nervous reaction to his near-death experience with a house cat, but he’d be okay to drive home if he just gave himself a minute.

Bast was a mess, the cat’s tail and hind leg braided together at disturbing angles, its throat mangled, and its innards draped over its wounds like the pulsing bodies of coiled nightcrawlers.

Marty watched the heat from the cat’s body seep into the spring night air. It smelled like his own rejuvenation and rebirth. Finally he felt strong enough to stand, brush the asphalt off his jeans, call the dog into the car, and put this night behind him. “Come on, Freya.”

But the dog was investigating something under the car next to him—the car he had been sitting against. The cat was nowhere to be seen, but there was a track of gore leading from where Bast had been to the underside of that other car, and he could hear an obscene yowling coming from there.

“Freya, get into our car…now!” said Marty, shooing her inside. Jumping into the driver’s seat, it wasn’t until he pulled onto the highway that he took another breath. “That cat—that damned cat—it still has a couple lives to work through. I don’t want to be there when it does.”

The lights from the highway rolled over the glass of the windshield and Marty flicked on the radio. Ted Nugent was singing “Cat Scratch Fever” and Marty laughed a laugh out of relief more than amusement. “Hey, Freya, how’s that for serendipity?”

But when he looked into the rear view mirror, he could see that Freya’s ears were flat and her tail was down. Anxiety rimmed the dog’s wide eyes.

Marty felt his smile fade under the weight of that stare, dreading the sinister yowl coming from the car’s undercarriage—the dead giveaway of a feline stowaway. He checked his gas gauge and calculated in his head how long he could keep the car moving. Not long enough.

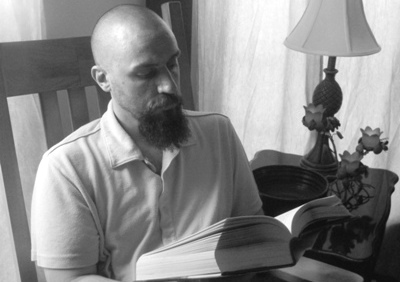

Christian A. Larsen grew up in Park Ridge, Illinois and graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He has worked as a high school English teacher, a radio personality, a newspaper reporter, and a printer's devil. His work has appeared in magazines such as Golden Visions, Lightning Flash, An Electric Tragedy, Eschatology, Indigo Rising, and Aphelion. He lives with his wife and two sons in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

Visit him online at www.exlibrislarsen.com and follow him on Twitter @exlibrislarsen.