The October Special Guest Writer is

Lisa Morton

Please feel free to visit Lisa HERE

HALLOWE'EN IN BLUE AND GRAY

by Lisa Morton

“The dead don’t come back, Nelly.”

It was after ten p.m. on October 31st, 1863 – Hallowe’en night. Johnny stood in the doorway to the parlor, eyeing his sister with a mix of anger and pathos. Nell sat by herself at a round table; before her was her childhood school slate, with chalk nearby. The room was lit by only a single candle on a sideboard, the curtains drawn so that no illumination entered from the street. Nell didn’t look at her brother.

“Give this up,” Johnny said.

“You can either join me or leave.” Nell’s voice was a soft monotone. She didn’t sound angry. She sounded determined. She sounded older than her eighteen years.

Johnny stepped closer but didn’t join her at the table. “Remember what happened a year ago?”

She still didn’t look up. “That was different. Everything was different.”

Johnny had to admit she was right about that.

*****

A year ago, they’d held a party on this night. The house had still known joy then, even surrounded by war.

Johnny and Nell’s parents had gone out to their own party, leaving their seventeen-year-old daughter, twelve-year-old son, and their children’s friends with old Nurse Janet, who’d looked after the children since Nell’s birth. The younger ones had started the evening with molasses pulling and bobbing for apples, a game which resulted in a shrieking argument when Willie Simpson accused Matthew Guild of pushing his head into the water just as he almost had an apple between his teeth. It had taken poor Janet five minutes, warm towels, and the promise of telling especially frightening ghost stories to calm them down.

Meanwhile, in the kitchen, Nell and her three friends Lulu Parks, Molly Evers, and Hannah Alexander were making a “dumb cake”. They moved about in silence, trying not to giggle as they formed small cakes out of flour, sugar, and butter. Once the cakes were made, they marked their initials in them, baked them, and set them on the kitchen table. Each took a chair nearby, waiting for apparitions of their future husbands to enter and claim a cake. When the girls had waited what they thought a sufficient amount of time and no such specters had entered, they’d exploded in talking and laughter as they’d eaten the cakes themselves while gossiping about boys.

About nine, Janet gathered both groups around her before the hearth, and while the older girls roasted nuts on the fire – naming them for various suitors and waiting to see which would pop first – the old Scottish woman entertained them all with the story of Red Mike.

“Red Mike was a strange one from his birth, an’ no wonder, for he first saw the light atween dusk an’ dark on a Hallowmas Eve. People thereabouts said that any bairn born on that night ran the risk o’ being possessed by dark fairies or worse.” Janet leaned forward for emphasis, and the listeners all clutched themselves, shivering in spite of the fire.

Red Mike, Janet went on, was a bad sort, causing all kinds of trouble to those around him. Finally, one Hallowe’en night he came to a party at the Flannigans’ house; he was courting Mary Flannigan, but she wanted nothing to do with Mike.

“Now,” Janet told her breathless listeners, “in those days they played a game on Hallowmas wi’ stalks of cabbage. They’d pull seven stalks from the garden and hand ‘em out to seven at the party while reciting this:

“One, two, three, and up to seven;

If all are white, all go to heaven;

If one is black as Murtagh’s evil,

He’ll soon be screechin’ wi’ the devil.

“Six got white stalks, but when it came time for Mike to reveal his, it was black an’ foul wi’ worms and slugs, and smelled like something dead. When all laughed, Mike said he carried special powers on account of being born on Hallowe’en, and he tried to curse the lot. But fortunately Father O’Connor was there, and when he stepped forward with a crucifix held before him Mike screamed like a banshee and ran off. The last anyone saw of him, he was still screamin’ and shoutin’ as he ran into a bog, and the bog just swallowed him up whole, so he was never seen again. To this day, that bog is still called Red Mike’s Rest.”

Finished with her story, Janet leaned back in her rocker, satisfied at the looks on the young faces gathered around her feet. None of them spoke a word until a knock at the front door made them all jump.

Parents had arrived to take the younger children home. Nell’s friends soon departed, Janet retired to bed, and Nell and Johnny were alone. Johnny had promised Janet that he’d go to bed, too, but he crept downstairs for one last bit of molasses candy. He was surprised to find his sister slumped over the kitchen table, looking glum. Even his attempt to frighten her with a covert tap on the shoulder was met with little beyond a heavy sigh.

“Didn’t you like the party?” Johnny asked.

“Oh, I liked the party well enough, but…Ned…”

He should’ve known. Ned. Of course. It was always Ned.

Nell was in love with their neighbor Ned Graham, and Johnny didn’t doubt that Ned loved his sister in return – he’d seen their furtive glances and smiles, so obvious that even a twelve-year-old could tell. He’d once spied them on a moonlit night in the garden kissing; when he’d teased his sister about it, she’d turned a glorious red and threatened him should he ever reveal what he’d seen to their parents. Johnny had enjoyed her huffing as he’d refused to agree, but they both knew that he had no intention of saying anything. The Barlowes had known the Grahams for ten years, ever since they’d arrived in the Ohio town from their native England – a land Johnny no longer had any memory of – and both families had commented on what a fine pair Ned and Nell made. Johnny found girls in general repulsive and hoped to never marry, but he liked Ned and would be happy to call him brother-in-law some day.

When Ned had enlisted in the Army two months ago, both sets of parents had been irate. “But Ned,” Johnny’s mother had argued, “you’ve got a fine future ahead of you taking over the Graham business.”

“I understand, Mrs. Barlowe,” Ned had answered, with his usual courtesy, “but there’s a war on. My country needs me. I have a duty to defend the Union, and besides – the Graham wood mill will still be here when I return.”

Nell had been even more vociferous in her opposition. “How could you, Ned Graham?”

But if his sister didn’t understand why Ned had signed on, Johnny did.

He thought being a soldier fighting a war on behalf of your nation must be the most splendid thing in the world. He read newspaper accounts from the front lines, of great battles and grand charges, and he imagined himself there, rifle held resolutely before him as he ran at the enemy, firing, bayoneting them, surviving fierce fights to emerge victorious. He would stand before President Lincoln, perhaps still healing from a wound or two, to accept his medals. The great man would shake his hand and thank him, and Johnny would answer, “I was honored to serve, Mr. President.”

Of course they’d all told him he couldn’t enlist at twelve. But he heard of other young boys who worked with the regiments. “Orphans,” his mother had said. “Nothing but boot-shiners, Ned,” his father had added.

Left with no alternative, he would live through Ned’s adventures, at least until he was old enough to join. Ned had written to Nell twice a week, telling her all about his training and his commanding officers and the other soldiers and the marching, the endless marching that made Johnny wonder when Ned would get to experience anything else.

“What time is it?” Nell abruptly looked up from the table, eyes darting for the kitchen clock.

“A few minutes before twelve.”

“There’s still time, then,” Nell breathed out excitedly as she rushed from the kitchen, “still time to see Ned tonight!”

Curious, Johnny followed as Nell ran to her bedroom, grabbed a mirror and a candle, and went to the cellar door. She opened the door, stepped onto the top stair, then turned around and held the mirror before her.

“You’re off your chump,” Johnny muttered, watching her in perplexity.

“No,” Nell answered, “don’t you remember what Janet said about Hallowe’en? She told us it’s the one night of the year when the veil between worlds lifts. All sorts of amazing things can happen on Hallowe’en. You can see ghosts, or meet a fetch.”

“A fetch?”

“The ghost of someone still alive. I read in a magazine about this old Hallowe’en charm: at exactly midnight, you descend the cellar stairs backward while looking in a mirror, and you’ll see the fetch of your beloved.”

Johnny was about to tell Nell that just confirmed his opinion of her mental state when the grandfather clock in the hallway began to strike.

“That’s it,” Nell said. She took a deep breath, hefted her skirts, and stepped backward.

Johnny waited on the landing, expecting to hear his sister cry out and tumble any second. What he did not expect was a deafening shriek as the clock struck twelve. As he stood paralyzed in shock, his sister exploded into the kitchen, her breath hastened by fear.

“Nell, what –”

“Something touched me! I thought I saw a face in the mirror, and then I felt a hand on my shoulder.”

Janet appeared from the main hallway, still pulling a dressing robe around her. “What is it?”

“I –”

Nell was about to answer when a young, masculine voice called from the cellar, “Nelly?”

She gasped, turned to the doorway – and Ned Graham stepped into view, grinning, looking dapper in his dark blue uniform.

They all called his name and rushed toward him. He hugged all three then looked at Nell’s shocked face. “I’m sorry, darling, that was a mean trick to play, but I couldn’t resist when I peeked through the cellar window and saw you on those stairs.”

“How did you get here?”

Ned wiped tears from her face, his own eyes brimming. “They gave us a few days’ furlough. I caught the first train back and just arrived.”

Janet took Johnny by the shoulder and guided him from the kitchen. “Come on, these two have a lot to catch up on.”

Johnny protested, “But I want to hear about the war!”

“Tomorrow.”

*****

The next day, Johnny was disappointed to hear that Ned had seen no fighting. Ned thought that might change soon, though, and promised to write down all the details for Johnny.

He also asked for Nell’s hand in marriage when he left the Army. The Barlowes agreed. Nell cried and promised to wait for him.

Two days later, Ned left on the train, leaning out the window for a last kiss from Nell before the train pulled out.

“He’ll be fine, dear,” Mrs. Barlowe said, her hand on her daughter’s arm.

Nell didn’t answer.

*****

Ned continued to write twice a week. He was unable to return home for the holidays, but assured them that the men in his regiment had made “a very merry Christmas eve.”

By the turn of 1863, Johnny was thrilled to read that Ned had been involved in a few skirmishes. In March, he finally fired his rifle for the first time, but confessed that he couldn’t be sure he’d hit anything.

In late April and May, the Confederates gained ground with their victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville, and in June the Northern soldiers were unsuccessful in repelling the South as they crossed the Potomac and pushed into Maryland.

On June 25th, Ned told them he was being sent to some place in Pennyslvania called Gettysburg. It was the last letter they received from him.

Nell grew increasingly frantic as newspapers filled with accounts of the fierce fighting at Gettysburg. Casualties ran high for both the blue and the gray. There was no word from Ned.

Johnny imagined Ned, stalwart and bold in his uniform, leading his men to take out entire squadrons of the rebels. He wished he was by Ned’s side, even if it was just to keep his guns loaded and sword oiled.

On July 6th, the train arrived with a new list of those lost in battle. The list was posted on the wall of the telegraph office. Nell was there with Ned’s parents.

She crumpled when she saw his name.

Mr. and Mrs. Graham, nearly as distraught as Nell, pulled her with them as they returned to a house that would be forever empty of a son’s voice. Mr. and Mrs. Barlowe carried Nell to her room.

Johnny didn’t believe it.

“It’s a mistake,” he insisted. “They got the names wrong.”

But a few days later the Grahams received a letter that they shared with the Barlowes. It was from a young man who had served with Ned, but had escaped injury. It said Ned had been near a cannonball strike and had been blown nearly to bits.

Over the next four months, Johnny watched helplessly as his sister retreated from the world. On the rare occasions that she left her room, she moved listlessly, the light in her eyes dull. She read Ned’s letters over and over until the writing on the sheets was blurred by tears.

Johnny spent his time imagining terrible revenges enacted on rebel soldiers. He loaded and fired the cannon that destroyed an entire squadron. He charged into their midst, killing any still left alive. He ground his foot into one man’s wound, smiling grimly when the gray shrieked for mercy.

Summer became fall, and then October, and then Hallowe’en.

Johnny attended Willie Simpson’s Hallowe’en party, but mostly sat in a corner by himself, barely noticing the festivities. He knew the others whispered about him, but he didn’t care.

At nine, Janet collected him. “Don’t you like Hallowe’en, my boy?” she asked.

“Not so much,” he said.

Later, he found himself wandering down to the kitchen, believing the rest of the house to be in bed, when he saw Nell in the parlour, with slates and chalk. He knew that his sister had recently acquired – as had many others grieving over a loved one lost in the war – an interest in Spiritualism, which taught that spirits were real and helpful and could be contacted. Certainly there was no better night to contact the dead than Hallowe’en, that night when veils lifted.

“You can either join me or leave.”

Johnny stepped closer but didn’t join her at the table. “Remember what happened a year ago?”

She still didn’t look up. “That was different. Everything was different.”

Inwardly sighing, Johnny took a seat next to her. “So what do we do?”

Nell took both of his hands in hers. “We call out to him.” She looked up into the shadowed high corners of the room. “He’s here. I’m sure of it. I can feel him.”

Johnny shifted uncomfortably in his chair. He didn’t feel anything except a little scared by the look on his sister’s face.

Nell closed her eyes and tilted her head back. “Ned Graham, we are asking you to join us. We call out to you, Ned, to cross over and speak to us.”

The candle flame flickered.

Nell opened her eyes. “Darling, are you here? It’s me, Nelly. Johnny’s here, too. We’ve left a slate and chalk for you to write on.”

Johnny was surprised to find himself staring at the slate, expecting to see writing appear there any instant.

When several seconds went by, Nell called out, “Ned, I know you’re out there. Give us some sign, please. Anything.”

The glass in the nearest window thudded as if something had been slapped against it. Johnny jumped, but Nell held fast to his hands. “Yes! I knew it, darling – you are here!”

Johnny saw nothing but black night outside the window; even the moonlight was obscured by a thick blanket of clouds.

“Talk to us, Ned.”

There was a pounding on the outer wall of the house, to the left of the window, as if something was moving around the side of the house toward the front.

Nell began to cry. “Ned, I’ve missed you so much, and now you’re here –”

Johnny yanked his hands from Nell’s. “Somebody’s outside the house, Nell.”

“Yes, it’s Ned –“

Johnny didn’t believe ghosts could pound that solidly on walls and windows. He lit a lantern, stood indecisively for a few seconds...

There was a single huge knock on the front door.

Nell leapt from her chair, excitedly, but Johnny placed himself between her and the door. “Nell, don’t –”

The knocking came again, and again – now a slow, ominous, repeated sound.

Nell pushed past Johnny, ignoring him. All Johnny could do was run after her. “Nell –!”

“I’m coming, Ned!”

Nell reached the door, grasped the knob, twisted it, and threw the door back as Johnny joined her.

Ned Graham stood there…or at least most of him stood there.

He was four months dead by cannon blast. His left side was a wasteland of flesh, bone, and tattered blue uniform. The lower jaw hung partly loose, held to his head only by the right joint. The left eye socket was shattered, leaving nothing but a viscous mess. The arm on that side was gone. Ribs and organs protruded from the left side of the torso.

But the skin might have been the worst part, for it had turned the color of the Confederates.

“Ned,” Nell said as she reached out.

Instinct claimed Johnny, the instinct to defend a loved one. He leapt forward, pushed his sister back, and slammed the door just as Ned thrust his right hand forward. Johnny pushed hard, fighting the hand that kept the door from closing. He mustered all his strength, heard a sickly crunching sound, the hand was withdrawn and the door clicked shut. Johnny threw the lock, falling against the door in exhaustion as the dead man on the other side pounded against it.

Nell regained her footing and rushed forward, staring at Johnny with wide eyes. “What are you doing?”

Confused, Johnny couldn’t form an answer.

“That’s Ned out there,” she continued.

Still panting, Johnny could only stare at his sister for a moment, at the madness in her. “That thing is dead, Nell.”

“I don’t care. I brought him back, my Ned. Move away from the door.”

On the other side of the door, Ned continued to hammer, slow blows powerful enough to rattle the door in its frame.

When Johnny refused to move, Nell said, piteously, “But he wants me.”

Ned struck the door again, strongly enough to make Johnny stagger, and he feared the door would soon give way, trapping him between his sister and the dead man. He thought furiously then remembered what was in the closet just a few steps away.

He rushed forward, pulled open the closet door, and retrieved his father’s old shotgun. Father had taken him hunting with it just last month. Johnny had cried when they’d shot a rabbit, and Father had asked him what kind of soldier he’d make if he cried over animals. Later, Johnny went hungry rather than take a single bite of the rabbit stew Janet had made.

But he knew how to use the gun. He cracked it open, pulled down a cartridge from a shelf nearby, shoved it in, snapped the gun closed, and turned back to the front entry.

Nell was fumbling with the door lock. She finally managed it, threw it back, flung the door open, and reached for Ned.

Their fingers met just for a second – withered gray flesh and pink, living skin.

Then Johnny ran forward, again pushed his sister aside, and fired at Ned.

The buckshot collided with Ned’s head, creating an explosion of pulp and bone. Ned collapsed.

Nell screamed.

Johnny, deafened from the sound of the blast in the house, stumbled forward, past his sister, to see that Ned hadn’t simply collapsed – he’d vanished. Nothing remained but dust the color of an autumn storm.

Johnny jumped as a hand reached around him to take the shotgun, but he saw it was only Janet. The old Scotswoman set the gun aside and put an arm around Johnny. He fell into her, grateful, uncaring about his sister’s madness or his own sobbing. When he was able to form words, he asked, “Did you see it, too? It was Ned, come back.”

Janet shook her head. “No, child – it was a Hallowe’en boggart. A bogey, nothing more.”

Nell stopped screaming and slid to the floor, her eyes hollow, defeated. Johnny knew that even if she regained her sanity, she would never forgive him.

With that realization came another: he saw the lies behind the façade of courage, sacrifice, honor; he saw the death and ruination that defined war.

He pulled away from Janet, took the shotgun from her, and returned it to the closet.

“Are you all right, boy?” his old nurse asked.

Johnny offered her a wan smile. “I’m fine, but…I’m not a boy.”

With that he went to help his sister back to her room.

Photo credit: Seth Ryan

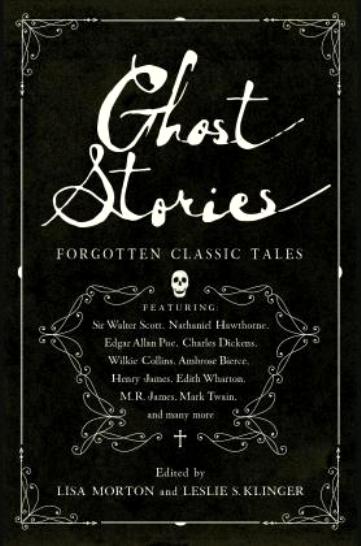

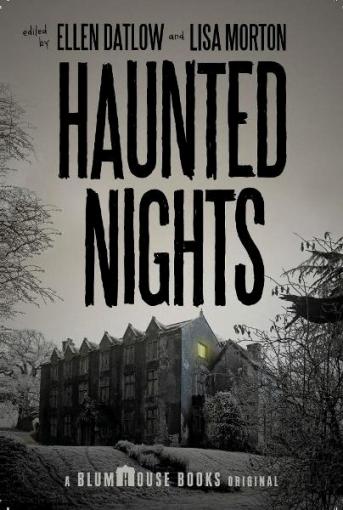

Lisa Morton is a screenwriter, author of non-fiction books, Bram Stoker Award®-winning prose writer, and Halloween expert whose work was described by the American Library Association’s Readers’ Advisory Guide to Horror as “consistently dark, unsettling, and frightening.” She has published four novels, 150 short stories, and three books on the history of Halloween. Her most recent releases include the anthologies Haunted Nights (co-edited with Ellen Datlow) and Ghost Stories: Classic Tales of Horror and Suspense (co-edited with Leslie Klinger), both of which received starred reviews in Publishers Weekly; forthcoming in 2020 is Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances.

She lives in the San Fernando Valley, and can be found online at www.lisamorton.com