Who else is buried in Richard III's Leicester car park graveyard?

Richard's body was found last year, and now we know he had a roommate

IN THE ARCHIVES:

Arm Bones

Amelia

Robobees

Tarantula

Meteorites

Coffin Therapy

Strange Street Signs

Catfish Hunt on Land

See a film clip HERE

The medieval stone coffin at the Greyfriars site in Leicester was buried close to the body of Richard III. Photograph: University of Leicester/EPA

The Guardian, August 1 -- The Leicester municipal car park that, amid much fanfare, yielded the remains of King Richard III has yet to give up all its long-buried secrets. Barely a year after archaeologists from the University of Leicester uncovered a skeleton confirmed in February as that of England's last Plantagenet monarch, they have exhumed a second body.

But whereas Richard's remains, hastily buried by members of the Greyfriars monastic community after the king's humiliation on Bosworth Field in 1485, lay in a humble hole in the ground, these are in a sealed lead casket within a limestone coffin. The Leicester team in fact uncovered the coffin last summer but left it where it was, preferring instead to focus their efforts on the excavation of Richard III's remains, which captured the world's imagination.

They have now returned to it, and speculation as to the possible identity of the mystery body inside has predictably been fevered, not least on Guardian comment threads: Lord Lucan? Jimmy Hoffa? Richard's long-lost horse, his horse, his kingdom for a horse? But while laboratory analysis, to be carried out later this year, may not necessarily positively identify the body (and positive identification isn't necessarily the point anyway), the archaeologists think they have a good idea of who it may be.

Records exist of a medieval Leicestershire knight called Sir William Moton who was buried in the Greyfriars church in 1362 – well over a century before Richard's demise. Sir William, believed to have been born in nearby Peckleton, where he also lived, is recorded as having married twice, to Joan, with whom he had a son, Robert, and to Elisabeth. There are other candidates, but few likely to have been interred in such grandeur. Peter Swynsfeld, who died in 1272, and William of Nottingham, who died in 1330, both leaders of the English Franciscans, are known to be buried here.

The team are also hoping they may find the headless remains of three Franciscan friars hanged and then beheaded for treason in 1402 on the orders of Henry IV. Roger Frisby, Walter Walton and John Moody were accused of spreading rumors that the deposed King Richard II was still alive and planning to retake the throne. The men's decapitated bodies, after being displayed in Oxford and London Bridge, were subsequently lost, but it is thought possible they were claimed and eventually buried by sympathizers at Greyfriars.

See the entire article HERE

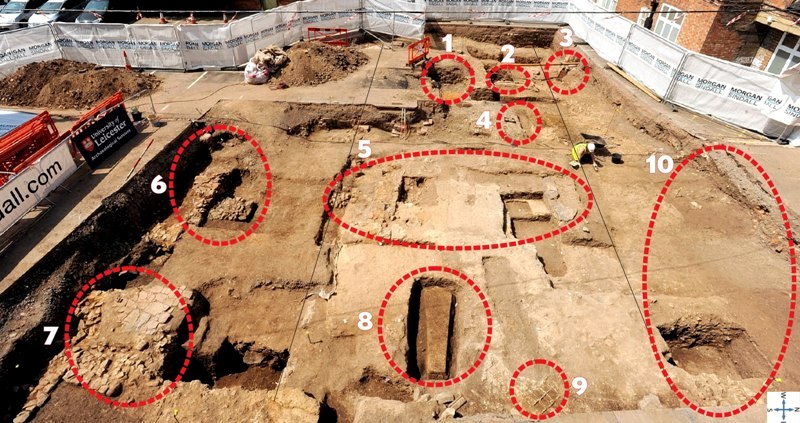

1) Richard III – discovered during the first dig in August 2012: This is the spot where the last English monarch to be killed in battle was unceremoniously buried following his death at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

His grave was discovered by the same team of archaeologists who are now working on this site.

The spot has been covered in a protective sheet and filled with sand to preserve it temporarily until a long-term solution can be found. It will be the main attraction at the Richard III visitor centre.

A glass ceiling will be placed over it so people can look down and see the 528-year-old grave for themselves – before exiting through the gift shop.

2) Intact floor tiles: A rare section of friary floor which survived the Dissolution of the Monasteries and 500-years of being buried and the mattocks of the university dig team.

Examples of these tiles can be found scattered throughout the site, but this is the only place where they can be seen in situ.

Other tiles were found in graves, used as backfill, such as the one at location 9.

3) Victorian well and leaky sewer: Not part of the friary or Herrick's garden, but an example of the wealth of archaeology from different periods found at the Greyfriars site.

Victorian builders were responsible for destroying Richard III's feet after they built foundations for a wall on top of them.

However, as Mat Morris said: "It could have been a lot worse!"

The leaky sewer is part of the council offices and not archaeology, although it does add an authentic medieval whiff to the site.

4) Peter Warzynski's trench: Full of broken tiles and dirt. Read more about my attempts at archaeology in Monday's Mercury.

5) Choir of the church and high-status burials (shown in the artist's impression): This part of the church would have included wooden choir stalls and had a resonant floor – which meant the friars' hymns and chants would have reverberated and echoed beautifully throughout the building.

The small pit (centre left) is a high-status burial, which was placed in the choir and can be seen on the artist's impressions.

It is not known who the grave belongs to. Two burials (centre right) have been discovered here, but not yet excavated.

They might be removed for their protection as the new Richard III visitor centre will occupy this spot when it is constructed later this year.

6) Wall and buttress: A new feature of the friary not found on any maps or in records of the site.

The remaining foundations of this medieval wall, built to the south of the abbey complex, might have been an extension to the church, or could have been unconnected and used simply as a boundary wall.

7) Herrick's path: This small section of pathway in Herrick's garden was made from re-used Roman tiles, as was the norm in past years.

Many of the buildings which were constructed throughout Leicester's historical periods were built from the remains of earlier structures, which makes archaeologists' lives a little harder when it comes to dating buildings.

8) Stone coffin: The final resting place of either Sir William Moton (a 14th century knight), Peter Swynsfeld (one of the friary's founders, who died in 1272) or William of Nottingham, who died in 1330.

This would have been located within the presbytery of the church, behind the choir and would have been reserved for a high-ranking member of society. The tomb is due to be opened on Tuesday.

9) Tile impressions: A surviving section of floor with the imprint of medieval tiles.

However, the tiles are long gone.

10) Graveyard (outside): This section of the friary would have been outside the walls of the building and most probably used as a graveyard.

It extends underneath the viewing platform and to the road, with potentially hundreds of graves.

See more HERE

King Richard III

Notice the curved spine (so history was correct: Richard III did have a curved spine):

About King Richard III

Richard was born on 2 October 1452 at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire. His father was Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York and his mother Cecily Neville. Richard was King of England for two years, from 1483 until his death in 1485 in the Battle of Bosworth Field. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat at Bosworth Field, the decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses, is sometimes regarded as the end of the Middle Ages in England. He is the subject of the play Richard III by William Shakespeare.

Richard had a claim to the English throne through both parents. We now know that Richard had a curvature of the spine, but the withered arm and limp of legend are almost certainly either fabrications or greatly exaggerated.

When Edward died in April 1483, Richard was named as protector of the realm for Edward's son and successor, the 12-year-old Edward V. As the new king travelled to London from Ludlow, Richard met him and escorted him to the capital, where he was lodged in the Tower of London. Edward V's brother later joined him there.

A publicity campaign was mounted condemning Edward IV's marriage to the boys' mother, Elizabeth Woodville, as invalid and their children illegitimate. On 25 June, an assembly of lords and commoners endorsed these claims. The following day, Richard III officially began his reign. He was crowned in July. The two young princes disappeared in August and were widely rumoured to have been murdered by Richard.

In August 1485, Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, who was a Lancastrian claimant to the throne living in France, landed in South Wales. He marched east and engaged Richard in battle on Bosworth Field in Leicestershire on 22 August. Although Richard possessed superior numbers, several of his key lieutenants defected. Refusing to flee, Richard was killed in battle and Henry Tudor took the throne as Henry VII.

Read the entire article HERE

See more HERE