FICTION BY GARRETT ROWLAN

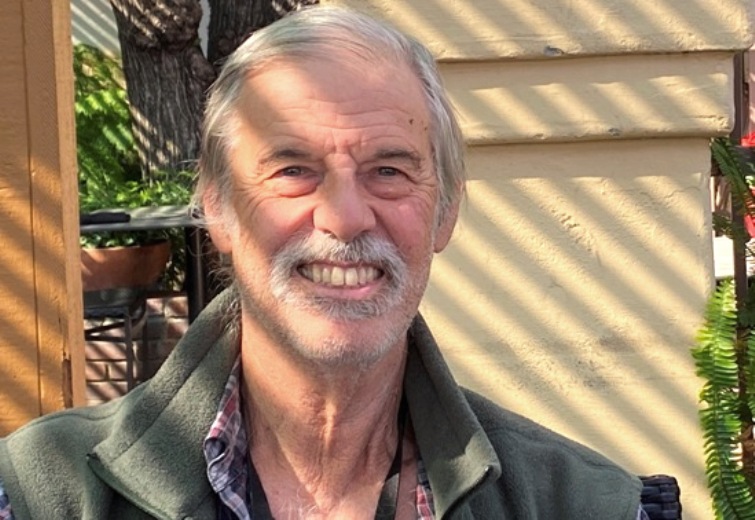

Garrett Rowlan is a retired teacher who lives in Los Angeles with two cats. He has work forthcoming in two anthologies and a magazine. His website is garrettrowlan@com.

THE LAST JOHN COLE

by Garrett Rowlan

Levin Osiris stepped off the bus where the road curled and the wealthy neighborhood disdained municipal transportation. He walked uphill past big houses and wide lawns. Halfway up, he stopped to catch his breath, turning and looking at the spread of the Los Angeles city lights.

How marvelous were real things, he thought, recalling those deluded writers—John Cole among them—who wanted to make reality “magical.” Reality was magical enough, and the real world had more magic—more complexity—than any truncated world of an author’s imagination, as Levin well knew.

And as his creator, John Cole, would soon find out.

The writer had made him a private eye, a being confined to the printed page until one day when Levin walked away from Cole’s traffic accident, leaving behind billowing smoke and cracked glass. He had been conceived on the page and birthed in distraction, a driver running a light, looking at his phone.

Crime writer John Cole, stunned, in shock, didn’t see an ectomorphic Levin leave the page, and Levin, feeling ever more solid, like a slowly filled cup, didn’t realized what happened until, minutes later, he saw his face in the windshield reflection. These were the features that Cole had described in novels. An ambulance wailed past him.

Begging, borrowing, and stealing, Levin survived and otherwise researched the reclusive John Cole, leading to his present arrival at the hill’s summit. This was the place, the last house on the right. Beyond, the hillside dropped off to produce a view that alone was worth six figures.

*****

The property was gated, and past the bars a wide, flat lawn led to the Doric columns that buttressed the porch. Pushing on an intercom button, Levin waited until he heard a voice from inside say, “Yes?”

“It’s me,” Levin said. For days, he had slipped notes inside the property, announcing his existence.

A curtain moved in the big house like a squinting eye. Levin wondered what Cole must be thinking, seeing how the character he created now stood at his gate, as if each time Cole had written the name Levin Osiris a little blood, bone, and skin had incubated somewhere, waiting to be birthed in the collision of metal.

At the sound of a click, Levin pushed on a wheezing, wrought-iron gate and entered the estate. Crossing a path where muted lights glowed in low shrubbery, he knocked on a door that remained closed, as if Cole had second thoughts about letting him in, but Levin pounded until the door opened.

The two men, creator and creation, regarded each other. Cole had created Levin in his own image, though the matching features were slightly younger in Levin’s case.

At last, as if stepping back from a canvas he’d painted, Cole wordlessly ushered Levin into a large front room of austere, shadowy illumination. Levin’s eyes went to the bookcase. Seeing the three first-edition novels that featured Levin Osiris, the Extreme Private Eye, Levin felt as if his own DNA were bound in buckram.

Cole cleared his throat and asked the magic question.

“Whiskey and water and two cubes of ice,” Levin said. “As if you didn’t know.”

Cole directed Levin to a high-backed recliner. While his host and creator poured, Levin looked around Cole’s lair, at the frowning portraits of antecedent Coles, stern men of hard eyes and downturned, thin lips. At the end of a hallway and a mullioned back door, he saw a garden with roses.

As Cole approached holding the drink, Levin watched him, sized up his slightly stilted walk—arthritis, perhaps, a malady Cole had not passed on. He made me younger, Levin realized, to recapture something of his own lost youth.

“The resemblance is remarkable,” Cole said, handing him the drink. Wearing a checkered suit and bow tie, his gray hair crew-cut and taut, he asked, “How did you find me?”

“The clues were in the books,” Levin said, “if you knew how to look. So I sent you a letter. It was a shot in the dark, I admit. But now that I’m here—”

Cole waved his hand, cutting him off. “Let’s talk about your letter. In it, you stated that reading my books woke up your memory. You remembered things, details. Do you recall that?”

“Of course,” Levin said.

“There are things I need to ask you if you are who you say you are.”

“I’m Levin Osiris, Invest—”

“Yes yes,” Cole said, impatiently. “But you could be some deranged fan or an opportunist of some sort.”

“I’m not!”

“But if you are,” Cole said, and he reached inside his sports jacket and showed Levin a pistol, “just remember I’m holding this.”

Levin drew back.

“Only a precaution,” Cole said, sliding the gun back into place. “I’m going to ask a few questions. If, as you say, you read my books and that woke your memory, I’d like to know a few things that only the real Levin Osiris would know.” Without waiting for an answer, Cole pulled out a slip of paper. “What was Georgia’s original name in The Last Bloodsucking Wife?”

“How would I know that?”

“I wrote each version and rewrote them. You lived through each draft. What was her name?”

Levin closed his eyes. Drafts, he thought. I have lived through drafts.

He thought of an open window, shifting the molecules in a room, stirring shadows, and a puddle of clothes on the floor. The woman in bed slipped a gold chain around her neck. There was a name attached.

“Carla,” he said.

“Yes,” Cole said, as if surprised. He turned the paper in his hands, reading another question. “What were the office hours of the vampire scholar Rupert Miles in Vintage Blood?”

“What is this, some kind of game show?”

“Answer the question,” Cole said. He touched the gun in his pocket.

“The hours, I see.” Sitting in some library or bookstore, Levin had read and reread the books in which he had appeared. He recalled a sentence. Gabbing from the vantage of his tenure, Rupert Miles opined on the theory of vampire evolution.

“In the novel, the passages unpublished,” Cole said, waiting. “That’s what I want to hear.”

“Yes,” Levin said. It popped into his mind, like a flower pressed between pages. “He was a professor who only taught night classes. Who never attended faculty meetings, whose office hours in summer would begin at eight at night.”

“Right,” Cole said. Frowning, he put the paper aside. “By the time I finished the final draft, Zoom technology allowed him to consult remotely, though the killing was still done up close and personal.”

Cole looked at Levin with respect, or perhaps disdain. “Your existence…you said it began with the accident, the car that t-boned me.” He frowned. “I was stunned, I recall. On the front seat was the manuscript of my latest novel. I bled all over it.” Cole made a bitter rumble. “After my editor had shit all over it, claimed the writing was stale, uninspired.”

“Leaving the accident,” Levin said, “I felt alive, I felt…more solid. I can’t put it any better than that. I had existed before, I know that now, but it was a paper-thin consciousness. When you bled into me, you gave me weight, a new density.” As if to demonstrate, he rapped his knuckles against the table on which he’d set his drink. “I felt things in a new way. Later, when I saw my name in a library book, the words were like cracked eggshells from which I emerged.”

Cole nodded. “I projected myself into your fictional world. You returned the favor, projected yourself into mine.” Cole’s ruminative expression sharpened. “And now you want a better life, that’s what your letter said.”

“Yes, I want your help,” Levin said. He took a sip of whiskey. “But it goes both ways. I can help you, too.”

“You can?”

Levin said, “I read an interview you did a year or so ago. In it, you said you were burned out on the Extreme Private Eye; that you found another novel hard to do. I’m here to help. I conceived a new version of my character, of myself. I understand him now. I’ve even started to scribble a little in my spare time. What better person to tell the history of the Extreme Private Eye than myself?”

“I see. You have something to show me, a manuscript?”

“I have ideas,” Levin said. “I thought you could write them up.”

“Why don’t you write them yourself?” Cole said.

“I’ve tried,” Levin said. “It’s not as easy as it looks.”

“Tell me about it,” Cole said. He chuckled bitterly. “Just remember to change the name if you do. Otherwise, I might be tempted to sue.” Cole took a drink. “As for your birth, it was something that happened, an accident of the imagination, or something…I don’t know. Point is, I didn’t intend it. Don’t blame me.”

Levin saw Cole’s hand tremble and remembered that in the latter Osiris Levin novels, the detective had a problem with alcohol. In that moment, he felt a surge of contempt for his creator.

“You think you can create me and just leave me like this?”

“Oh honestly,” Cole said. “You’re free. You can do anything you want.”

“Anything I want? I’m stuck in a world I didn’t make.”

“Then make that world,” Cole said. He took a drink, his eyes glassy. “Anyway, you seem to be surviving on your own. That’s good; I’m proud of you.”

“Surviving is not living.” Levin came out of his chair. He looked at Cole who again touched the gun in his pocket. As if dissuaded, Levin walked back and forth like a sentry on duty. He stopped and turned. “I’ll give you ideas and you write them up!”

“It doesn’t work that way.” Cole stood. “It wasn’t my idea to invite you here. I said you could come over for a drink and you’ve had that drink.” He lowered his chin slightly. “I’d like you to leave.”

“I can make trouble for you,” Levin said.

Cole withdrew the pistol. “Will this make you leave?”

Levin stepped back. He had faced guns before in Cole’s novels, but seeing the weapon aimed at his gut produced a visceral reaction, an intestinal blushing that was new, and convincing. “Okay,” he said, backing up.

As he walked toward the front, Levin realized that if he walked through that door, he would cut himself away from his chance to escape homelessness, poverty, scorn.

As he’d done in books, he spun and knocked the gun from Cole’s grasp. It fell to the floor. The two men grappled for the gun, resulting in one muffled shot.

Later, well past midnight, hidden from the high walls that Cole had built to discourage prying neighbors and even the occasional fan, Levin worked at midnight. He dug around the roses, and when he had a pit well more than deep enough, he threw in a body and covered it up as a new day dawned.

*****

The upstairs’ section of the bookstore was crowded, so much so that the store’s Community Rep, in introducing the author, made some remarks about the Fire Marshall, and what he’d say about the room conditions if he happened to arrive. With that, she introduced John Cole.

Cole stood, bowed to applause, and read from the fourth installment of the Extreme Private Eye. The book was called Lightning Strikes Twice. Levin Osiris now had to infiltrate a criminal organization whose secret weapon was a machine capable of duplicating humans, making mindless, destructive zombies.

A brief Q and A followed. Hands were raised, and Levin pointed at a blonde-haired woman who asked him how he got into his characters’ heads.

“Ventriloquism, disguises, playacting,” Cole said. “I have to feel that each character is a part of myself, before I can put him or her down on the page.”

A man in middle-age asked, “Why have you decided to have a book tour, after being considered a recluse all these years?”

“I felt the need to circulate,” Cole said. “I had become too solitary; I needed to get out, to meet my public.” He chuckled. “I needed to sell, which made my publisher happy.”

Someone else said, “I had heard you were giving up on writing.”

“I reread my previous novels. I broke them down, and only then did I feel capable of writing again.”

“This is not a question,” a woman said. “But you look much younger than the jacket photograph on your first book.”

“I didn’t like that photograph,” Cole said. “And to be honest, I’ve had a little work done.”

The audience chuckled, relieved in a way that the author had a human, vulnerable side.

“When can we expect the next book in the series?” someone asked.

“I don’t know. They get harder and harder. Someone once described writing as writing a line and then taking it out. How true that is. I almost had to recreate myself as I wrote this one. I had to reach inside myself and examine the psyche of Levin Osiris until c’est moi. Frankly, I’d like to get rid of him, if he’ll let me. I don’t think he likes being on the sidelines.”

Later, he signed. A female admirer said she was a writer herself. “Though hardly on your level,” she added. She was leaning forward, the top of her blouse sagging and revealing her breasts. “I’d really like to pick your brain.”

“If you feel that way,” John Cole said. “Perhaps we could meet.” When she nodded, he said he was staying at a prominent hotel chain, located a mile down the street. “I’ve been to three cities today,” he added, “I’d love to have someone to unwind with.”

“What’s your room number?”

He was going to say they could meet in the lounge, but cleavage made him want to cut to the chase—why not? He mumbled three digits.

“I’ll be there in an hour,” she said. “I’ll knock three times.”

She left him with a wink. The next customer set down her newly-bought hardbound book.

“Who should I sign it to?”

*****

The blonde left the bookstore and hooked the top two buttons on her blouse. She walked into the parking lot, all the way to its far edge where John Cole waited, a year after he died in his own home.

“He took the bait,” she said. She told him the room number. “Wow,” she added, “you do look like him. Only older. And frankly a lot worse for wear.”

What if you were buried for almost a week? Cole thought.

“Good,” was all he said. He glanced at the book the woman held. “And you can keep that if you want.”

“Hell no.” The woman tossed the signed book into the trash. “Reading is for losers.”

“Maybe,” he said, “but writing is for those who want to stay alive, well, sort of alive.”

“What does that mean?”

“Nothing,” he said. It would be hard to explain, to tell how as his corpse began to decompose, the splash of blood that came from Levin in the struggle gifted him with some kind of life-in-death volition, as if Levin had repaid the circumstances of his creation. Slowly he somehow managed to burrow up through the deep hollow that Levin took all night to dig.

She made the money sign, and he slipped bills to her.

She walked away. He watched her with a faint tinge of lust. That was good. He was becoming more human. He recalled how his body, freed from the rose garden dirt, and plagued with rigor mortis in some parts, rotted tissue and oozing sores in others, made him cry before the sliding glass door.

After crawling over a back fence, he moved among the detritus of Los Angeles, his walk still slightly lurching: the reconstruction of himself had not been perfect. He hid in abandoned homeless encampments, under bridges, dumpsters. It gave him a new perspective.

He found a way. Once his sores healed to something like a mild case of leprosy, he found work at a gas station, his ID had been kept in the wallet that he used to get employment, being paid under the table. He didn’t want to surface yet. This alternate version of himself required a phased rollout. His face in the mirror slowly cycled back to something he recognized. Only when the new John Cole novel was published was he, in a sense, prepared to self-publish himself.

Now he was ready. The van to transport the body ready and gassed. The grave in the desert already dug, waiting for Levin the impostor. Cole watched him leave the parking lot and soon followed. The motel was a mile down Colorado. He would knock three times, wait for the door to open, and strike.

And once it was done, the body buried, he would resume his old life and perhaps even write again. He had plenty of new material.