The January 2010 Special Guest Story is by Graham Masterton

Please feel free to visit Graham at:

UNDERBED

by Graham Masterton

As soon as his mother had closed the bedroom door, Martin burrowed down under the blankets. For him, this was one of the best times of the day. In that long, warm hour between waking and sleep, his imagination would take him almost anywhere.

Sometimes he would lie on his back with the blankets drawn up to his nose and his pillow on top of his forehead so that only his eyes looked out. This was his spaceman game, and the pillow was his helmet. He travelled through sparkling light-years, passing Jupiter so close that he could see the storms raging on its surface, then swung on to Neptune, chilly and green, and Pluto, beyond. On some nights he would travel so far that he was unable to return to Earth, and he would drift further and further into the outer reaches of space until he became nothing but a tiny speck winking in the darkness and he fell asleep.

At other times, he was captain of a U-boat trapped thousands of feet below the surface. He would have to squeeze along cramped and darkened passageways to open up stopcocks, with water flooding in on all sides, and elbow his way along a torpedo tube in order to escape. He would come up to the surface into the chilly air of the bedroom, gasping for breath.

Then he would crawl right down to the very end of the bed, where the sheets and the blankets were tucked in really tight. He was a coalminer, making his way through the narrowest of fissures, with millions of tons of carboniferous rock on top of him.

He never took a flashlight to bed with him. This would have revealed that the inside of his space-helmet didn’t have any dials or knobs or breathing tubes; and that the submarine wasn’t greasy and metallic and crowded with complicated valves; and that the grim black coal-face at which he so desperately hewed was nothing but a clean white sheet.

Earlier this evening he had been watching a programme on pot-holing on television and he was keen to try it. He was going to be the leader of an underground rescue team, trying to find a boy who had wedged himself in a crevice. It would mean crawling through one interconnected passage after another, then down through a water-filled sump, until he reached the tiny cavern where the boy was trapped.

His mother sat on the end of the bed and kept him talking. He was going back to school in two days’ time and she kept on telling him how much she was going to miss him. He was going to miss her, too, and Tiggy, their golden retriever, and everything here at Home Hill. More than anything, he was going to miss his adventures under the blankets. You couldn’t go burrowing under the bedclothes when you were at school. Everybody would rag you too much.

He had always thought his mother was beautiful and tonight was no exception, although he wished that she would go away and let him start his pot-holing. What made her beauty all the more impressive was the fact that she would be thirty-three next April, which Martin considered to be prehistoric. His best friend’s mother was only thirty-three and she looked like an old lady by comparison. Martin’s mother had bobbed brunette hair and a wide, generous face without a single wrinkle; and dark brown eyes that were always filled with love. It was always painful, going back to school. He didn’t realize how much it hurt her, too: how many times she sat on his empty bed when he was away, her hand pressed against her mouth and her eyes filled with tears.

“Daddy will be back on Thursday,” she said. “He wants to take us all out before you go back to school. Is there anywhere special you’d like to go?”

“Can we go to that Chinese place? The one where they give you those cracker things?”

“‘Pang’s? Yes, I’m sure we can. Daddy was worried you were going to say McDonald’s.”

She stood up and kissed him. For a moment they were very close, face-to-face. He didn’t realize how much he looked like her -- that they were both staring into a kind of a mirror. He could see what he would have looked like, if he had been a woman; and she could see what she would have looked like, if she had been a boy. They were two different manifestations of the same person, and it gave them a secret intimacy that nobody else could understand.

“Good night,” she said. “Sweet dreams.” And for a moment she laid a hand on top of his head as if she could sense that something momentous was going to happen to him. Something that could take him out of her reach forever.

“Good night, Mummy,” he said, and kissed her cheek, which was softer than anything else he had ever touched. She closed the door.

He lay on his back for a while, waiting, staring at the ceiling. His room wasn’t completely dark: a thin slice of light came in from the top of the door, illuminating the white paper lantern that hung above his bed so that it looked like a huge, pale planet (which it often was). He stayed where he was until he heard his mother close the living-room door, and then he wriggled down beneath the blankets.

He cupped his hand over his mouth like a microphone and said, “Underground Rescue Squad Three, reporting for duty.”

“Hello, Underground Rescue Squad Three. Are we glad you’re here! There’s a boy trapped in Legg’s Elbow, 225 metres down, past Devil’s Corner. He’s seventeen years old, and he’s badly injured.”

“Okay, headquarters. We’ll send somebody down there straight away.”

“It’ll have to be your very best man . . . it’s really dangerous down there. It’s started to rain and all the caves are flooding. You’ve probably got an hour at the most.”

“Don’t worry. We’ll manage it. Roger and out.”

Martin put on his equipment. His thermal underwear, his boots, his backpack and his goggles. Anybody who was watching would have seen nothing more than a boy-shaped lump under the blankets, wriggling and jerking and bouncing up and down. But by the time he was finished he was fully dressed for crawling his way down to Devil’s Corner.

His last radio message was, “Headquarters? I’m going in.”

“Be careful, Underground Rescue Squad Three. The rain’s getting heavier.”

Martin lifted his head and inhaled a lungful of chilly bedroom air. Then he plunged downwards into the first crevice that would take him down into the caves. The rock ceiling was dangerously low, and he had to crawl his way in like a commando, on his elbows. He tore the sleeve of his waterproof jacket on a protruding rock and he gashed his cheek, but he was so heroic that he simply wiped away the blood with the back of his hand and carried on crawling forward.

It wasn’t long before he reached a tight, awkward corner, which was actually the end of the bed. He had to negotiate it by lying on his side, reaching into the nearest crevice for a handhold, and heaving himself forward inch by inch. He had only just squeezed himself around this corner when he came to another, and had to struggle his way around it in the same way.

The air in the caves was growing more and more stifling, and Martin was already uncomfortably hot. But he knew he had to go on. The boy in Legg’s Elbow was counting on him, just like the rest of Underground Rescue Squad Three, and the whole world above ground, which was waiting anxiously for him to emerge.

He wriggled onwards, his fingers bleeding, until he reached the sump. This was a 10-metre section of tunnel which was completely flooded with black, chill water. Five pot-holers had drowned in it since the caves were first discovered, two of them experts. Not only was the sump flooded, it had a tight bend right in the middle of it, with rocky protrusions that could easily snag a pot-holer’s belt or his backpack. Martin hesitated for a moment, but then he took a deep breath of stale air and plunged beneath the surface.

The water was stunningly cold, but Martin swam along the tunnel with powerful, even strokes until he reached the bend. Still holding his breath, he angled himself sideways and started to tug himself between the jagged, uncompromising rocks. He was almost through when one of the straps on his backpack was caught and he found himself entangled. He twisted around, trying to reach behind his back so that he could pull the strap free from the rock, but he succeeded only in winding it even more tightly. He tried twisting around the other way, but now the strap tightened itself into a knot.

He had been holding his breath for so long now that his lungs were hurting. Desperately, he reached into his pocket and took out his clasp knife. He managed to unfold the blade, bend his arm behind his back and slash at the tightened strap. He missed it with his first two strokes, but his third stroke managed to cut it halfway through. His eyes were bulging and he was bursting for air, but he didn’t allow himself to give in. One more cut and the strap abruptly gave way.

Martin kicked both legs and swam forward as fast as he could. He reached the end of the sump and broke the surface, taking in huge grateful breaths of frigid subterranean air.

He had beaten the sump, but there were more hazards ahead of him. The rainwater from the surface was already beginning to penetrate the lower reaches of the cave system. He could hear water rushing through crevices and clattering through galleries. In less than half an hour, every pot-hole would be flooded, and there would be no way of getting back out again.

Martin pressed on, sliding on his belly through a fissure that was rarely more than 30 centimetres high. He was bruised and exhausted, but he had almost reached Devil’s Corner. From there, it was only a few metres to Legg’s Elbow.

Rainwater trickled from the low limestone ceiling and coursed down the side of the fissure, but Martin didn’t care. He was already soaked and he was crawling at last into Devil’s Corner. He slid across to the narrow vertical crevice called Legg’s Elbow and peered down it, trying to see the trapped boy.

“Hallo!” he called. “Is anybody there? Hallo, can you hear me? I’ve come to get you out!”

Martin listened but there was no answer. There wasn’t even an imaginary answer. He forced his head further down, so that he could see deeper into the crevice, but there was nobody there. Nobody crying; nobody calling out. No pale distressed face looking back up at him.

He had actually reached the bottom of the bed, and was looking over the edge of the mattress, into the tightly-tucked dead-end of blankets and sheets.

He had a choice, but there was very little time. Either he could climb down Legg’s Elbow to see if he could find where the boy was trapped, or else he could give up his rescue mission and turn back. In less than twenty minutes, the caves would be completely flooded, and anybody down here would be drowned.

He decided to risk to it. It would take him only seven or eight minutes to climb all the way down Legg’s Elbow, and another five to crawl back as far as the sump. Once he was back through the sump, the caves rose quite steeply towards the surface, so that he would have a fair chance of escaping before they filled up with water.

He pushed his way over the edge of Legg’s Elbow, and began to inch down the crevice. He could slip at any moment, and his arms and legs were shaking with effort. He could feel the limestone walls starting to move -- a long slow seismic slide that made him feel as if the whole world were collapsing all around him. If Legg’s Elbow fell in, he would be trapped, unable to climb back out, while more and more rainwater gushed into the underground caverns.

Panting with effort, he tried to cling on to the sides of the crevice. There was one moment when he thought he was going to be able to heave himself back. But then everything slid - sheets, blankets, limestone rocks, and he ended up right at the bottom of Legg’s Elbow, buried alive.

For a moment, he panicked. He could hardly breathe. But then he started to pull at the fallen rockslide, tearing a way out of the crevice stone by stone. There had to be a way out. If there was a deeper, lower cavern, perhaps he could climb down to the foot of the hill and crawl out of a fox’s earth or any other fissure he could locate. Afterall, if the rainwater could find an escape-route through the limestone, he was sure that he could.

He managed to heave all of the rocks aside. Now all he had to do was burrow through the sludge. He took great handfuls of it and dragged it behind him, until at last he felt the flow of fresh air into the crevice: fresh air, and wind. He crawled out of Legg’s Elbow on his hands and knees, and found himself lying on a flat, sandy beach. The day was pearly-grey, but the sun was high in the sky and the ocean peacefully glittered in the distance. He turned around and saw that, behind him, there was nothing but miles and miles of grey tussocky grass. Somehow he had emerged from these tussocks like somebody emerging from underneath a heavy blanket.

He stood up and brushed himself down. He was still wearing his waterproof jacket and his pot-holing boots. He was glad of them, because the breeze was thin and chilly. Up above him, white gulls circled and circled, not mewing or crying, their eyes as expressionless as sharks’ eyes. In the sand at his feet tiny iridescent shells were embedded.

For a moment, he was unable to decide what he ought to do next, and where he ought to go. Perhaps he should try to crawl back into the pot-hole, and retrace his route to the surface. But he was out in the open air here, and there didn’t seem to be any point in it. Besides, the pot-hole was heavily covered in grass, and it was difficult to see exactly where it was. He thought he ought to walk inland a short way, to see if he could find a road or a house or any indication of where he might be.

But then, very far away, where the sea met the sky, he saw a small fishing-boat drawing in to the shore, and a man climbing out of it. The fishing-boat had a russet-coloured triangular sail, like a fishing-boat in an old-fashioned watercolour. He started to walk towards it; and then, when he realized how far it was, he started to run. His waterproof jacket made a chuffing noise and his boots left deep impressions in the sand. The seagulls kept pace with him, circling and circling.

Running and walking, it took him almost twenty minutes to reach the fishing-boat. A white-bearded man in olive-coloured oilskins was kneeling down beside it, stringing fat triangular fish on to line. The fish were brilliant, and they shone with every colour of the rainbow. Some of them were still alive, thrashing their tails and blowing their gills.

Martin stopped a few yards away and watched and said nothing. Eventually the man stopped stringing fish and looked up at him. He was handsome, in an old-fashioned way -- chiselled, like Charlton Heston. But his eyes were completely blank: the colour of sky on an overcast day. He reminded Martin of somebody familiar, but he couldn’t think who he was.

Not far away, sitting cross-legged on a coil of rope, was a thin young boy in a hooded coat. He was playing a thin, plaintive tune on a flute. His wrists were so thin and the tune was so sad that Martin almost felt like crying.

“Well, you came at last,” said the man with eyes the colour of sky. “We’ve been waiting for you.”

“Waiting for me? Why?”

“You’re a tunneller, aren’t you? You do your best work underground.”

“I was looking for a boy. He was supposed to be stuck in Legg’s Elbow, but -- I don’t know. The whole cave system was flooded, and it seemed to collapse.”

“And you thought that you escaped?”

“I did escape.”

The man stood up, his waterproofs creaking. He smelled strongly of fresh-caught fish, all that slime on their scales. “That was only a way of bringing you here. We need you to help us, an experienced tunneller like you. What do you think of these fish?”

“I never saw fish like that before.”

“They’re not fish. Not in the strictest sense of the word. They’re more like ideas.”

He picked one up, so that it twisted and shimmered; and Martin could see that it was an idea, rather than a fish. It was an idea about being angry with people you loved; and how you could explain that you loved them, and calm them down. Then the man held up another fish; and this was a different fish altogether, a different idea. This was a glittering idea about numbers: how the metre was measured by the speed of light. If light could be compressed, then distance could, too -- and the implications of that were quite startling.

Martin couldn’t really understand how the fish managed to be ideas as well as fish; but they were; and some of the ideas were so beautiful and strange that he stood staring at them and feeling as if his whole life was turning under his feet.

The sun began to descend towards the horizon. The small boy put away his flute and helped the fisherman to gather the last of his lines and his nets. The fisherman gave Martin a large woven basket to carry, full of blue glass fishing-floats and complicated reels. “We’ll have to put our best foot forward, if we want to get home before dark.”

They walked for a while in silence. The breeze blew the sand in sizzling snakes, and behind them the sea softly applauded, like a faraway audience. Afterfour or five minutes, though, Martin said, “Why do you need a tunneller?”

The fisherman gave him a quick, sideways glance. “You may not believe it, but there’s another world, apart from this one. A place that exists right next to us, like the world that you can see when you look in a mirror . . . essentially the same, but different.”

“What does that have to do with tunnelling?”

“Everything, because there’s only one way through to this world, and that’s by crawling into your bed and through to the other side.”

Martin stopped in his tracks. “What the hell are you talking about, bed? I tunnel into caves and pot-holes, not beds.”

“There’s no difference,” said the fisherman. “Caves, beds, they’re just the same . . . a way through to somewhere else.”

Martin started walking again. “You’d better explain yourself.” The sun had almost reached the horizon now, and their shadows were giants with stilt-like legs and distant, pin-size heads.

“There isn’t much to explain. There’s another world, beneath the blankets. Some people can find it, some can’t. I suppose it depends on their imagination. My daughter Leonora always had the imagination. She used to hide under the blankets and pretend that she was a cave-dweller in prehistoric times; or a Red Indian woman, in a tent. But about a month ago she said that she had found this other world, right at the very bottom of the bed. She could see it, but she couldn’t wriggle her way into it.”

“Did she describe it?”

The fisherman nodded. “She said that it was dark, very dark, with tangled thorn-bushes and branchy trees. She said that she could see shadows moving around in it - shadows that could have been animals, like wolves; or hunched-up men wearing black fur cloaks.”

“It doesn’t sound like, the kind of world that anybody would want to visit.”

“We never had the chance to find out whether Leonora went because she wanted to. Two days ago my wife went into her bedroom to discover that her bed was empty. We thought at first that she might have run away. But we’d had no family arguments, and she really had no cause to. Then we stripped back her blankets and found that the lower parts of her sheets were torn, as if some kind of animal had been clawing at it.”

He paused, and then he said, with some difficulty, “We found blood, too. Not very much. Maybe she scratched herself on one of the thorns. Maybe one of the animals clawed her.”

By now they had reached the grassy dunes and started to climb up them. Not far away there were three small cottages, two painted white and one painted pink, with lights in the windows, and fishing nets hung up all around them for repair. “Didn’t you try going after her yourself?” asked Martin.

“Yes. But it was no use. I don’t have enough imagination. All I could see was sheets and blankets. I fish for rational ideas -- for astronomy and physics and human logic. I couldn’t imagine Underbed so I couldn’t visit it.”

“Underbed?”

The fisherman gave him a small, grim smile. “That’s what Leonora called it.”

They reached the cottage and laid down all of their baskets and tackle. The kitchen door opened and a woman carne out, wiping her hands on a flowery apron. Her blonde hair was braided on top of her head and she was quite beautiful in an odd, expressionless way, as if she were a competent oil-painting rather than a real woman.

“You’re back, then?” she said. “And this is the tunneller?”

The fisherman laid his hand on Martin’s shoulder. “That’s right. He came, just like he was supposed to. He can start to look for her tonight.”

Martin was about to protest, but the woman carne up and took hold of both of his hands. “I know you’ll do everything you can,” she told him. “And God bless you for corning here and trying.”

*****

They had supper that evening around the kitchen table -- a rich fish pie with a crispy potato crust, and glasses of cold cider. The fisherman and his wife said very little, but scarcely took their eyes away from Martin once. It was almost as if they were frightened that he was going to vanish into thin air.

On the mantelpiece, a plain wooden clock loudly ticked out the time, and on the wall next to it hung a watercolour of a house that for some reason Martin recognized. There was a woman standing in the garden, with her back to him. He felt that if she were able to turn around he would know at once who she was.

There were other artefacts in the room that he recognized: a big green earthenware jug and a pastille-burner in the shape of a little cottage. There was a china cat, too, which stared at him with a knowing smile. He had never been here before, so he couldn’t imagine why all these things looked so familiar. Perhaps he was tired, and suffering from déjà vu.

After supper they sat around the range for a while and the fisherman explained how he went out trawling every day for idea-fish. In the deeper waters, around the sound, there were much bigger fish, entire theoretical concepts, swimming in shoals.

“This is the land of ideas,” he said, in a matter-of-fact way. “Even the swallows and thrushes in the sky are little whimsical thoughts. You can catch a swallow and think of something you once forgot; or have a small, sweet notion that you never would have had before.

“You -- you come from the land of action, where things are done, not just discussed.”

“And Underbed? What kind of a land is that?”

“I don’t know. The land of fear, I suppose. The land of darkness, where everything always threatens to go wrong.”

“And that’s where you want me to go looking for your daughter?”

The fisherman’s wife got up from her chair, lifted a photograph from the mantelpiece and passed it across to Martin without a word. It showed a young blonde girl standing on the seashore in a thin summer dress. She was pale-eyed and captivatingly pretty. Her bare toes were buried in the sand. In the distance, a flock of birds were scattering, and Martin thought of ‘small, sweet notions that you never would have had before.’

Martin studied the photograph for a moment and then gave it back. “Very well, then,” he said. “I’ll have a try.” After all, it was his duty to rescue people. He hadn’t been able to find the boy trapped in Legg’s Elbow: perhaps he could redeem himself by finding Leonora.

Just after eleven o’clock they showed him across to her room. It was small and plain, except for a pine dressing-table crowded with dolls and soft toys. The plain pine bed stood right in the middle of the longer wall, with an engraving of a park hanging over it. Martin frowned at the engraving more closely. He was sure that the park was familiar. Perhaps he had visited it when he was a child. But here, in the land of ideas?

The fisherman’s wife closed the red gingham curtains and folded down the blankets on the bed.

“Do you still have the sheets from the time she disappeared?” Martin asked her.

She nodded, and opened a small pine linen-chest at the foot of the bed. She lifted out a folded white sheet and spread it out on top of the bed. One end was ripped and snagged, as if it had been caught in machinery, or clawed by something at least as big as a tiger.

“She wouldn’t have done this herself,” said the fisherman. “She couldn’t have done.”

“Still,” said Martin. “If she didn’t do it, what did?”

*****

By midnight Martin was in bed, wearing a long white borrowed nightshirt, and the cottage was immersed in darkness. The breeze persistently rattled the window-sash like somebody trying to get in; and beyond the dunes Martin could hear the sea. He always thought that there was nothing more lonely than the sea at night.

He didn’t know whether he believed in Underbed or not. He didn’t even know whether he believed in the land of ideas or not. He felt as if he were caught in a dream -- yet how could he be? The bed felt real and the pillows felt real and he could just make out his pot-holing clothes hanging over the back of the chair.

He lay on his back for almost fifteen minutes without moving. Then he decided that he’d better take a look down at the end of the bed. After all, if Underbed didn’t exist, the worst that could happen to him was that he would end up half-stifled and hot. He lifted the blankets, twisted himself around, and plunged down beneath them.

Immediately, he found himself crawling in a low, peaty crevice that was thickly tangled with tree-roots. His nostrils were filled with the rank odour of wet leaves and mould. He must have wriggled into a gap beneath the floor of a wood or forest. It was impenetrably dark, and the roots snared his hair and scratched his face. He was sure that he could feel black-beetles crawling across his hands and down the back of his collar. He wasn’t wearing nightclothes any longer. Instead, he was ruggedly dressed in a thick checkered shirt and heavy-duty jeans.

After 40 or 50 metres, he had to crawl right beneath the bole of a huge tree. Part of it was badly rotted, and as he inched his way through the clinging taproots, he was unnervingly aware that the tree probably weighed several tons and if he disturbed it, it could collapse into this subterranean crevice and crush him completely. He had to dig through heaps of peat and soil, and at one point his fingers clawed into something both crackly and slimy. It was the decomposed body of a badger that must have become trapped underground. He stopped for a moment, suffocated and sickened, but then he heard the huge tree creaking and showers of damp peat fell into his hair, and he knew that if he didn’t get out of there quickly he was going to be buried alive.

He squirmed out from under the tree, pulling aside a thick curtain of hairy roots, and discovered that he was out in the open air. It was still night-time, and very cold, and his breath smoked in the way that he and his friends had pretended to smoke on winter mornings when they waited for the bus for school -- which was, when? Yesterday? Or months ago? Or even years ago?

He stood in the forest and there was no moon, yet the forest was faintly lit by an eerie phosphorescence. He imagined that aliens might have landed behind the trees. A vast spaceship filled with narrow, complicated chambers where a space-mechanic might get lost for months, squeezing his pelvis through angular bulkheads and impossibly-constricted service-tunnels.

The forest was silent. No insects chirruped. No wind disturbed the trees. The only sound was that of Martin’s footsteps, as he made his way cautiously through the brambles, not sure in which direction he should be heading. Yet he felt that he was going the right way. He felt drawn: magnetized, almost, like a quivering compass-needle. He was plunging deeper and deeper into the land of Underbed: a land of airlessness and claustrophobia, a land in which most people couldn’t even breathe. But to him, it was a land of closeness and complete security.

Up above him, the branches of the trees were so thickly entwined together that it was impossible to see the sky. It could have been daytime up above, but here in the forest it was always night.

He stumbled onwards for over half an hour. Every now and then he stopped and listened, but the forest remained silent. As he walked on he became aware of something pale, flickering behind the trees, right in the very corner of his eye. He stopped again, and turned around, but it disappeared, whatever it was.

“Is anybody there?” he called out, his voice muffled by the encroaching trees. There was no answer, but now Martin was certain that he could hear dry leaves being shuffled, and twigs being softly snapped. He was certain that he could hear somebody breathing.

He walked further, and he was conscious of the pale shape following him like a paper lantern on a stick, bobbing from tree to tree, just out of sight. But although it remained invisible it became noisier and noisier, its breath coming in short, harsh gasps, its feet rustling faster and faster across the forest floor.

Suddenly, something clutched at his shirtsleeve -- a hand, or a claw -- and ripped the fabric. He twisted around and almost lost his balance. Standing close to him in the phosphorescent gloom was a girl of sixteen or seventeen, very slender and white-faced. Her hair was wild and strawlike, and backcombed into a huge birdsnest, decorated with thorns and holly and moss and shiny maroon berries. Her irises were charcoal-grey -- night-eyes, with wide black pupils. Eyes that could see in the dark. Her face was starved-looking but mesmerically pretty. It was her white, white skin that had made Martin believe that he was being followed by a paper lantern.

Her costume was extraordinary and erotic. She wore a short blouse made of hundreds of bunched-up ruffles of grubby, tattered lace. Every ruffle seemed to be decorated with a bead or a medal or a rabbit’s-foot, or a bird fashioned out of cooking-foil. But her blouse reached only as far as her navel, and it was all she wore. Her feet were filthy and her thighs were streaked with mud.

“What are you searching for?” she asked him, in a thin, lisping voice.

Martin was so confused and embarrassed by her half-nakedness that he turned away. “I’m looking for someone, that’s all.”

“Nobody looks for anybody here. This is Underbed.”

“Well, I’m looking for someone. A girl called Leonora.”

“A girl who came out from under the woods?”

“I suppose so, yes.”

“We saw her passing by. She was searching for whatever it is that makes her frightened. But she won’t find it here.”

“I thought this was the land of fear.”

“Oh, it is. But there’s a difference between fear, isn’t there, and what actually makes you frightened?”

“I don’t understand.”

“It’s easy. Fear of the dark is only a fear. It isn’t anything real. But what about things that really do hide in the dark? What about the coat on the back of your chair that isn’t a coat at all? What about your dead friend standing in the corner, next to your wardrobe, waiting for you to wake?”

“So what is Leonora looking for?”

“It depends what’s been frightening her, doesn’t it? But the way she went, she was heading for Under-Underbed; and that’s where the darkest things live.”

“Can you show me the way?”

The girl emphatically shook her head so that her beads rattled and her ribbons shook. “You don’t know what the darkest things are, do you?” She covered her face with her hands, her fingers slightly parted so that only her eyes looked out. ‘The darkest things are the very darkest things; and once you go to visit them in Under-Underbed, they’ll know which way you came, they’ll be able to smell you, and they’ll follow you back there.’

Martin said, “I still have to find Leonora. I promised.”

The girl stared at him for a long, long time, saying nothing, as if she were sure that she would never see him again and wanted to remember what he looked like. Then she turned away and beckoned him to follow.

They walked through the forest for at least another twenty minutes. The branches grew sharper and denser, and Martin’s cheeks and ears were badly scratched. All the same, with his arms raised to protect his eyes, he followed the girl’s thin, pale back as she guided him deeper and deeper into the trees. As she walked, she sang a high-pitched song.

The day’s in disguise

It’s wearing a face I don’t recognize

It has rings on its fingers and silken roads in its eyes

Eventually they reached a small clearing. On one side the ground had humped up, and was thickly covered with sodden green moss. Without hesitation the girl crouched down and lifted up one side of the moss, like a blanket, revealing a dark, root-wriggling interior.

“Down there?” asked Martin, in alarm.

The girl nodded. “But remember what I said. Once you find them, they’ll follow you back. That’s what happens when you go looking for the darkest things.”

“All the same, I promised.”

“Yes. But just think who you promised, and why. And just think who Leonora might be; and who I am; and what it is you’re doing here.”

“I don’t know,” he admitted; and he didn’t. But while the girl held the moss-blanket as high as she could manage, he climbed on to his side and worked his way underneath it, feet-first, as if he were climbing into bed. The roots embraced him, they took him into their arms like thin-fingered women, and soon he was buried in the mossy hump up to his neck. The girl knelt beside him and her face was calm and regretful. For some reason her nakedness didn’t embarrass him any more. It was almost as if he knew her too well. But without saying anything more, she lowered the blanket of moss over his face and his world went completely dark.

He took a deep, damp-tasting breath, and then he began to insinuate his way under the ground. At first, he was crawling quite level, but he soon reached a place where the soil dropped sharply away into absolute blackness. He thought he could feel a faint draft blowing, and the dull sound of hammering and knocking. This must be it: the end of Underbed, where Under-Underbed began. This was where the darkest things lived. Not just the fear, but the reality.

For the first time since he had set out on his rescue mission he was tempted to turn back. If he crawled back out of the moss-blanket now, and went back through the forest, then the darkest things would never know that he had been here. But he knew that he had to continue. Once you plunged into bed, and Underbed, and Under-Underbed, you had committed yourself.

He swung his legs over the edge of the precipice, clinging with both hands on to the roots that sprouted out of the soil like hairs on a giant’s head. Little by little, he lowered himself down the face of the precipice, his shoes sliding in the peat and bringing down noisy cascades of earth and pebbles. The most frightening part about his descent was that he couldn’t see anything at all. He couldn’t even see how far down he had to climb. For all he knew, the precipice went down and down for ever.

Every time he clutched at a root, he couldn’t help himself from dragging off its fibrous outer covering, and his hands soon became impossibly slippery with sap.

Below him, however, the hammering had grown much louder, and he could hear echoes too, and double-echoes.

He grasped at a large taproot, and immediately his hand slipped. He tried to snatch a handful of smaller roots, but they all tore away, with a sound like rotten curtains tearing. He clawed at the soil itself, but there was nothing that he could do to stop himself from falling. He thought, for an instant: I’m going to die.

He fell heavily through a damp, lath-and-plaster ceiling. With an ungainly wallop he landed on a sodden mattress, and tumbled off it on to a wet-carpeted floor. He lay on his side for a moment, winded, but then he managed to twist himself around and climb up on to his knees. He was in a bedroom -- a bedroom which he recognized, although the wallpaper was mildewed and peeling, and the closet door was tilting off its hinges to reveal a row of empty wire hangers.

He stood up, and went across to the window. At first he thought it was night-time, but then he realized that the window was completely filled in with peat. The bedroom was buried deep below the ground.

He began to feel the first tight little flutters of panic. What if he couldn’t climb his way out of here? What if he had to spend the rest of his life buried deep beneath the surface, under layers and layers of soil and moss and suffocating blankets? He tried to think what he ought to do next, but the hammering was now so loud that it made the floor tremble and the hangers in the closet jingle together.

He had to take control of himself. He was an expert, after all: a fully-trained pot-holer, with thirty years’ experience. His first priority was to find Leonora, and see how difficult it was going to be to get her back up the precipice. Perhaps there was another way out of Under-Underbed which didn’t involve 20 or 30 metres of dangerous climbing?

He opened the bedroom door and found himself confronted by a long corridor with a shiny linoleum floor. The walls were lined with doors and painted, with a tan dado, like a school or a hospital. A single naked light hung at the very far end of the corridor, and under this light stood a girl in a long white nightgown. Her blonde hair was flying in an unfelt wind, and her face was so white that it could have been sculpted out of chalk.

The hem of her nightgown was ripped into tatters and spattered with blood. Her calves and her feet were savagely clawed, with the skin hanging down in ribbons, and blood running all over the floor.

“Leonora?” said Martin, too softly for the girl to be able to hear. Then, “Leonora!”

She took one shuffling step towards him, and another, but then she stopped and leaned against the side of the corridor. It was the same Leonora whose photograph he had seen in the fisherman’s cottage, but three or four years older, maybe more.

Martin started to walk towards her. Ashe passed each door along the corridor, it seemed to fly open by itself. The hammering was deafening now, but the rooms on either side were empty, even though he could see armchairs and sofas and coffee-tables and paintings on the walls. They were like tableaux from somebody’s life, year by year, decade by decade.

“Leonora?” he said, and took her into his arms. She was very cold, and shivering. “Come on, Leonora, I’ve come to take you home.”

“There’s no way out,” she whispered, in a voice like blanched almonds. “The darkest things are coming and there’s no way out.”

“There’s always a way out. Come on, I’ll carry you.”

“There’s no way out!” she screamed at him, right in his face. “We’re buried too deep and there’s no way out!”

“Don’t panic!” he shouted back at her. “If we go back to the bedroom we can find a way to climb back up to Underbed! Now, come on, let me carry you!”

He bent down a little, and then heaved her up on to his shoulder. She weighed hardly anything at all. Her feet were badly lacerated. Two of her left toes were dangling by nothing but skin, and blood dripped steadily on to Martin’s jeans.

As they made their way back down the corridor, the doors slammed shut in the same way that they had flown open. But they were still 10 or 11 metres away from the bedroom door when Leonora clutched him so tightly round the throat that she almost strangled him, and screamed. “They’re here! The darkest things! They’re following us!”

Martin turned around, just as the lightbulb at the end of the corridor was shattered. In a single instant of light, however, he had seen something terrible. It looked like a tall, thin man in a grey monkish hood. Its face was as beatifically perfect as the effigy of a saint. Perfect, that is, except for its mouth, which was drawn back in a lustful grin, revealing a jungle of irregular, pointed teeth. And below that mouth, in another lustful grin, a second mouth, with a thin tongue-tip that lashed from side to side as if it couldn’t wait to start feeding.

Both its arms were raised, so that its sleeves had dropped back, exposing not hands but hooked black claws.

This was one of the darkest things. The darkest thing that Leonora had feared, and had to face.

In the sudden blackness, Martin was disoriented and thrown off balance. He half-dropped Leonora, but he managed to heft her up again and stumble in the direction of the bedroom. He found the door, groped it open and then slammed it shut behind them and turned the key.

“Hurry!” he said. “You’ll have to climb on to the bed-head, and up through the ceiling!”

They heard a thick, shuffling noise in the corridor outside, and an appalling screeching of claws against painted plaster walls. The bedroom door shook with a sudden collision and plaster showered down from the lintel. There was another blow, and then the claws scratched slowly down the door-panels. Martin turned around. In spite of her injured feet, Leonora had managed to balance herself on the brass bedrail, and now she was painfully trying to pull herself through the hole in the damaged ceiling. He struggled up on to the mattress to help her, and as the door was shaken yet again, she managed to climb through. Martin followed, his hands torn by splintered laths. Ashe drew his legs up, the bedroom door racketed open and he glimpsed the hooded grey creature with its upraised claws. It raised its head and looked up at him and both its mouths opened in mockery and greed.

The climb up the precipice seemed to take months. Together, Martin and Leonora inched their way up through soft, collapsing peat, using even the frailest of roots for a handhold. Several times they slipped back. Again and again they were showered with soil and pebbles and leaf-mould. Martin had to spit it out of his mouth and rub it out of his eyes. And all the time they knew that the darkest thing was following them, hungry and triumphant, and that it would always follow them, wherever they went.

Unexpectedly, they reached the crest of the precipice. Leonora was weeping with pain and exhaustion, but Martin took hold of her arm and dragged her through the roots and the soft, giving soil until at last they came to the blanket of moss. He lifted it up with his arm, trembling with exhaustion, and Leonora climbed out from under it and into the clearing. Martin, gasping with effort, followed her.

There was no sign of the forest-girl anywhere, so Martin had to guess the way back. Both he and Leonora were too tired to speak, but they kept on pushing their way through the branches side by side, and there was no doubt of their companionship. They had escaped from Under-Underbed, and now they were making their way back through Underbed and up to the worlds of light and fresh air.

It took Martin far longer than he thought to find the underground cavity which would take them back to Leonora’s world. But a strong sense of direction kept him going: a sense that they were making their way upwards. Just when he thought that they were lost for good, he felt his fingers grasping sheets instead of soil, and he and Leonora climbed out of her rumpled bed into her bedroom. Her father was sitting beside the bed, and when they emerged he embraced them both and skipped an odd little fisherman’s dance.

“You’re a brave boy, you’re a brave boy, bringing my Leonora back to me.”

Martin smeared his face with his hands. “She’s going to need treatment on her feet. Is there a doctor close by?”

“No, but there’s lady’s smock and marigolds; and myrtle, for dismissing bad dreams.”

“Her toes are almost severed. She needs stitches, not marigolds. She needs a doctor.”

“An idea will do just as well as a doctor.”

“There’s something else,” said Martin. “The thing that hurt her . . . I think it’s probably following us.”

The fisherman laid his hand on Martin’s shoulder and nodded. “We’ll take care of that, my young fellow.”

*****

So they stood by the shore in the mauvish light of an early summer’s evening and they set fire to Leonora’s bed, blankets and sheets and all, and they pushed it out to sea like an Arthurian funeral barge. The flames lapped into the sky like dragons’ tongues, and fragments of burned blanket whirled into the air.

Leonora with her bandaged feet stood close to Martin and held his arm; and when it was time for him to go she kissed him and her eyes were filled with tears. The fisherman gratefully clasped his hand. “Always remember,” he said. “What might have been is just as important as what actually was.”

Martin nodded; and then he started walking back along the shoreline, to the tussocky grass that would lead him back to Legg’s Elbow and the caves. He turned around only once, but by then it was too dark to see anything but the fire burning from Leonora’s bed, 300 metres out to sea.

*****

His mother frantically stripped back his sheets and blankets in the morning and found him at the bottom of the bed in his red-and-white striped pyjamas, his skin cold and his limbs stiff with rigor mortis. There was no saving him: the doctor said that he had probably suffocated some time after midnight, and by the time his mother found him he had been dead for seven-and-a-half hours.

When he was cremated, his mother wept and said that it was just as if Martin’s was a life that had never happened.

But who could say such a thing? Not the fisherman and his family, who went back to their imaginary cottage and said a prayer for the tunneller who rescued their daughter. Not a wild, half-naked girl who walked through a forest that never was, thinking of a man who dared to face the darkest things. And not the darkest thing which heaved itself out from under the moss and emerged at last in the world of ideas from a smoking, half-sunken bed; a hooded grey shape in the darkness.

And, in the end, not Martin’s mother, when she went back into his bedroom after the funeral to strip the bed.

She pulled back the blankets one by one; then she tugged off the sheets. But it was just when she was dragging out the sheets from the very end of the bed that she saw six curved black shapes over the end of the mattress. She frowned, and walked around the bed to see what they were.

It was only when she looked really close that she realized they were claws.

Cautiously, she dragged down the sheet a little further. The claws were attached to hands and the hands seemed to disappear into the crack between sheet and mattress.

This was a joke, she thought. Some really sick joke. Martin had been dead for less than a week and someone was playing some childish, hurtful prank. She wrenched back the sheet even further and seized hold of one of the claws, so that she could pull it free.

To her horror, it lashed out at her, and tore the flesh on the back of her hand. It lashed again and again, ripping the mattress and shredding the sheets. She screamed, and tried to scramble away, her blood spotting the sheets. But something rose out of the end of the bed in a tumult of torn foam and ripped-apart padding -- something tall and grey with a face like a saint and two parallel mouths crammed with shark’s teeth. It rose up and up, until it was towering above her and it was cold as the Arctic. It was so cold that even her breath fumed.

“There are some places you should never go,” it whispered at her, with both mouths speaking in unison. “There are some things you should never think about. There are some people whose curiosity will always bring calamity, especially to themselves, and to the people they love. You don’t need to go looking for your fears. Your fears will always follow you, and find you out.”

With that, and without hesitation, the darkest thing brought down its right-hand claw like a cat swatting a thrush and ripped her face apart.

Before she could fall to the carpet, it ripped her again, and then again, until the whole bedroom was decorated with blood.

It bent down then, almost as if it were kneeling in reverence to its own cruelty and its own greed, and it firmly seized her flesh with both of its mouths. Gradually, it disappeared back into the crevice at the end of the bed, dragging her with it, inch by inch, one lolling leg, one flopping arm.

The last to go was her left hand, with her wedding-ring on it.

Then there was nothing but a torn, bloodstained bed in an empty room, and a faint sound that could have been water trickling down through underground caves, or the sea, whispering in the distance, or the rustling of branches in a deep, dark forest.

Copyright © by Graham Masterton, 2003

Graham Masterton has published over 100 novels, including thrillers, horror novels, disaster epics, and sweeping historical romances.

He was editor of the British edition of Penthouse magazine before writing his debut horror novel The Manitou in 1975, which was subsequently filmed with Tony Curtis, Susan Strasberg, Burgess Meredith and Stella Stevens.

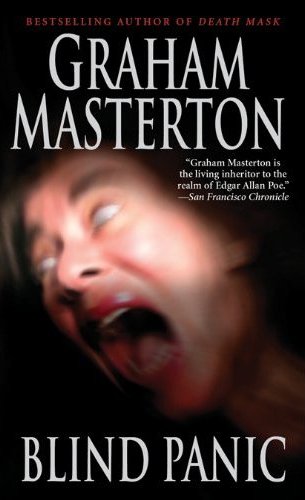

His latest novel, Blind Panic, is published by Leisure Books in January, 2010, and tells of a final devastating conflict between the characters that first appeared in The Manitou – Harry Erskine the phony mystic and Misquamacus the Native American wonder-worker.

After the initial success of The Manitou, Graham continued to write horror novels and supernatural thrillers, for which he has won international acclaim, especially in Poland, France, Germany, Greece and Australia.

His historical romances Rich (Simon & Schuster) and Maiden Voyage (St Martins) both featured in The New York Times Bestseller List. He has twice been awarded a Special Edgar by Mystery Writers of America (for Charnel House, and more recently Trauma, which was also named by Publishers Weekly as one of the hundred best novels of the year.)

He has won numerous other awards, including two Silver Medals from the West Coast Review of Books, a tombstone award from the Horror Writers Network, another gravestone from the International Horror Writers Guild, and was the first non-French winner of the prestigious Prix Julia Verlanger for bestselling horror novel. The Chosen Child (set in Poland) was nominated best horror novel of the year by the British Fantasy Society.

Several of Graham’s short stories have been adapted for TV, including three for Tony Scott’s Hunger series. Jason Scott Lee starred in the Stoker-nominated Secret Shih-Tan.

Apart from continuing with some of most popular horror series, Graham is now writing novels that have some suggestion of a supernatural element in them, but are intended to reach a wider market than genre horror.

Trauma (Penguin) told the story of a crime-scene cleaner whose stressful experiences made her gradually believe that a homicidal Mexican demon possessed the murder victims whose homes she had to sanitize. (This novel was optioned for a year by Jonathan Mostow.) Unspeakable (Pocket Books) was about a children’s welfare officer, a deaf lip-reader, who became convinced that she had been cursed by the Native American father of one of the children she had rescued. (This novel was optioned for two years by La Chauve Souris in Paris.)

Ghost Music is a love story in which a young TV-theme and ad-jingle composer discovers that his musical sensitivity allows him to see and feel very much more than anybody else around him – but with horrifying consequences which only he can resolve.

Other novels coming up soon from Leisure Books: Descendant, an idiosyncratic vampire novel; and Fire Spirit, about a vengeful child who was burned to death in a house fire.

Website: www.grahammasterton.co.uk for full biography and bibliography.