On this month's Morbidly Fascinating Page:

The life and death of the "Mad Monk" Rasputin, and what happened to Anatasia?

“The holy man is he who takes your soul and will and makes them his. When you choose your holy man, you surrender your will. You give it to him in utter submission, in full renunciation.” – Feodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

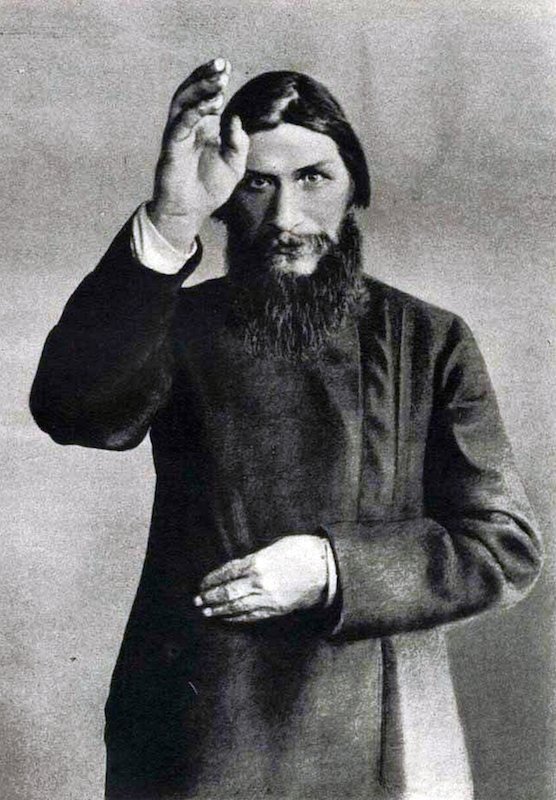

Who was Rasputin?

Gregory Rasputin was one of Russia's most controversial and mysterious figures who posed as a "holy man" and destroyed the political image and reputation of Russia's Emperor Tsar Nicholas II and his family through a series of political manipulations, scandals and treachery, provoking a huge wave of public anger and helping the communists to prepare the disastrous Russian revolution.

Tsar Nicholas was warned by his loyal prime minister, Count Stolypin, that Rasputin was a dangerous fraud who could become a threat to the royal family and to Russia. However, at Tsar Nicholas' insistence, Stolypin had a private meeting with Rasputin. Not long afterward Stolypin was assassinated by a hired terrorist, and the resulting investigation by the authorities was stopped order of the Emperor.

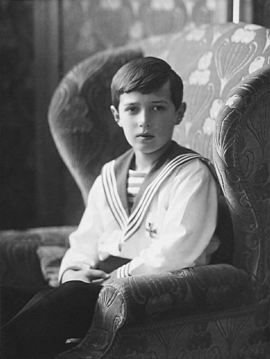

Rasputin apparently persuaded both the Empress and her ailing son to ensure that he kept a permanent presence in the tsar's palaces, and he was appointed to an official court position as "personal healer" to Crown Prince Aleksey Nikolaeyvitch Romanov, who suffered from Hemophilia, a genetic bleeding disorder where the blood doesn't clot properly due to a lack of clotting factors.

How did Rasputin integrate himself into the Royal Family?

When a 34-year-old Rasputin arrived in the Russian capital of St Petersburg in 1903, his timing couldn’t have been better. Interest in mysticism and the occult was growing among the city’s fashionable circles, and Rasputin was perfectly placed to take advantage of such a craze. For years, the illiterate Siberian peasant turned self-professed holy man (despite his nickname today, he was never a monk) had been travelling through Russia, and he claimed to have travelled as far as Greece and Jerusalem.

Having converted to a radical religious sect at the age of 18, he built a reputation as a healer – one who could predict the future and grant divine deliverance. This was achieved through his doctrine of ‘holy passionlessness’, which claimed that the best way to be closer to God was through sinful actions, especially those of the flesh. His flesh, to be exact. No wonder his name changed from Grigory Yefimovich Novykh to Rasputin, thought to mean ‘the debauched one’.

Despite his filthy hair and beard and malodorous appearance, Rasputin’s followers grew in number until even the Empress of Russia, Tsarina Alexandria, became interested.

Traditional doctors had been unable to treat the young Alexei – who suffered from haemophilia, meaning his blood wouldn’t clot properly whenever he was injured – so a desperate Alexandra turned to unorthodox healers. When Rasputin supposedly managed to stop a bad bleeding episode in 1908, through prayer, the Tsarina fell under his spell. Rasputin became “Our Friend” to the Romanov family, and was summoned whenever Alexei needed faith healing. In 1912, the Prince’s condition deteriorated so badly that he received the last sacrament. On hearing the news, Rasputin sent a telegram to Alexandra, reading: “The little one will not die. Do not allow the doctors to bother him too much.” Alexei recovered, Rasputin’s bond with the royals strengthened and his name spread throughout Russia.

The Romanov Family (sometimes spelled Romanoff)

The parents: Father Alexander and Mother Alexandria

Sister Tatiana, Sister Maria, Brother Alexi

Sister Anatasia (more about what happened to Anatasia below)

Rasputin's murder

Soldiers on World War I’s Eastern front spoke of Rasputin having an intimate affair with Alexandra, passing it off as common knowledge without evidence. As the war progressed, outlandish stories expanded to include Rasputin’s supposed treason with the German enemy, including a fantastical tale that he sought to undermine the war effort by starting a cholera epidemic in Saint Petersburg with “poisoned apples imported from Canada.” What the public thought they knew about Rasputin had a greater impact than his actual views and activities, fueling demands that he be removed from his position of influence by any means necessary.

The murder of Rasputin, Russia’s infamous “Mad Monk,” is the fodder for a great historical tale that blends fact and legend. But the death of the controversial holy man and faith healer had a combustible effect on the tense state of affairs in pre-revolution Russia. Rasputin was killed on December 30, 1916 (December 17 in the Russian calendar in use at the time), in the basement of the Moika Palace, the Saint Petersburg residence of Prince Felix Yussupov, the richest man in Russia and the husband of the Czar’s only niece, Irina. His battered body was discovered in the Neva River a few days later.

To the dismay of Yussupov and his co-conspirators, Rasputin’s murder did not lead to a radical change in Nicholas and Alexandra’s polities. To the emergent Bolsheviks, Rasputin symbolized the corruption at the heart of the Imperial court, and his murder was seen, rather accurately, as an attempt by the nobility to hold onto power at the continued expense of the proletariat. To them, Rasputin represented the broader problems with czarism. In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, Provisional Government leader Alexander Kerensky went so far as to say, "Without Rasputin there would have been no Lenin."

The Fall of the Romonov Family

The Romanov Family right before execution

Tsar Nicholas II's leadership was widely criticized as ineffective and out of touch with the needs of the Russian people. Russia's involvement in World War I exacerbated existing social and economic problems, leading to widespread discontent and unrest. The 1905 revolution, triggered by the Bloody Sunday massacre, demonstrated the growing dissatisfaction with the Tsar's rule and the desire for political reform. The influence of Grigori Rasputin, a self-proclaimed holy man, on the imperial family, particularly Empress Alexandra, fueled public anger and distrust of the Romanovs. The February Revolution of 1917, fueled by food shortages, military failures, and widespread strikes, led to the Tsar's abdication.

After his abdication, Emperor Nicholas and his family were under house arrest near St. Petersburg. The decision was made to liquidate the whole family, the family doctor, the three servants, and even the family dog. Thus, the reign of the Romanovs finally ended.

What happened to Anastasia?

The discovery of the Romanov graves involved a decades-long search and involved both amateur historians and official investigations. In 1979, amateur historians located the first grave near Yekaterinburg, but kept it secret for a decade. The site was exhumed in 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, revealing nine sets of remains. However, the bodies of Alexei and Anastasia were missing from the grave. That led to the speculation that both had somehow escaped and survived.

Who was Anna Anderson?

.

In 1920, Anderson was institutionalized in a mental hospital after a suicide attempt in Berlin. At first, she went by the name Fräulein Unbekannt (German for Miss Unknown) as she refused to reveal her identity. She resided in the institution until where she lived in anonymity until 1922, when she suddenly announced that she was none other the Grand Duchess Anastasia.

She became famous world-wide as thousands believed she was Anastasia, who had "myteriously escaped."

During the next few years, her entourage of Russian emigres grew, and she became particularly close to Gleb Botkin, who as the son of the slain Romanov family physician had spent considerable time with the imperial family in his childhood. During this time, numerous Romanov relatives and acquaintances interviewed her, and many were impressed by both her resemblance to Anastasia and her knowledge of the small details of the Romanov’s family life. Others, however, left skeptical when she failed to remember important events of young Anastasia’s life. Her knowledge of English, French, and Russian, which the young Anastasia knew how to speak well, were also significantly lacking. Many blamed these inconsistencies on her reoccurring mental illness, which led to short stays in mental institutions on several occasions.

Meanwhile, her supporters began a long battle to win her legal recognition as Anastasia. Such recognition would not only win her access to whatever Romanov riches remained outside the USSR but would make her a formidable political pawn of czarist exiles who still hoped to overthrow Russia’s communist leaders.

The Grand Duke of Hesse, Alexandra’s brother and Anastasia’s uncle, was a major critic of this effort, and he hired a private investigator to determine Anastasia Tschaikovsky’s true identity. The investigator announced that she was in fact Franziska Schanzkowska, a Polish-German factory worker from Pomerania who had disappeared in 1920.

So then, what really happened to Anastasia?

On July 29, 2007, a shallow grave in Russia’s Koptyaki Forest, just outside the city of Yekaterinburg, was unearthed. Inside the grave were forty-four charred bone and teeth fragments—the remains of Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanov and her little brother Alexei, and the twentieth century’s most notorious cold cases was sadly solved. No one in the family had escaped, and no one had survived.