FICTION BY NANCY HOLDER

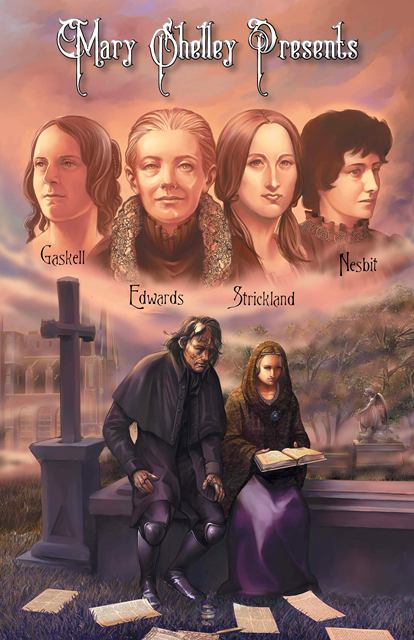

Nancy Holder is a New York Times bestselling author of over 90 novels and hundreds of short stories, comic books, essays, and articles. She has received 6 Bram Stokers, including this year's Graphic Novel award, for Mary Shelley Presents Tales of the Supernatural (Kymera Press.) She was honored as the 2019 Grand Master by the International Association of Media Tie-In Writers. She has written novels, episode guides, and other material for Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Teen Wolf, Wonder Woman, Ghostbusters, Hellboy, and many other shows and films. A devoted Sherlock Holmes enthusiast, she is a Baker Street Irregular and has written extensively about Holmes. She created the online game The Unsolved Cases of Sherlock Holmes for Storium™ and recently co-edited Sherlock Holmes of Baking Street for Belanger Books. She and her coauthor Alan Philipson are currently working on two comic book/graphic novel series for Moonstone Books and IFWG International.

CATFATHER

by Nancy Holder

He had seen death before. Death had birthed him. Death had brought rage and fury. But this death, this … his hour of triumph—

This singular moment was a grief that cracked his bones and drank his blood, and filled his boiling heart with shame. He wailed like a child, keened at the sight of the pallid face of Victor Frankenstein. Seconds too late. Too late. Frankenstein was dead. He had done this, he.

But it was done to me first.

No matter.

The smile of a loving father: never. The dreams and hopes for his future: none. Nothing but loathing for “the demon.” He did not love me. He could not. But he loved him now, loved Victor Frankenstein, the prideful, fragile man who had pursued him across ice and snow for the sole purpose of dealing him death. The madman who had pieced him together from limbs of rotting flesh, galvanized them, and, horrified, abandoned him.

Frankenstein had expired inside the cabin of the captain of a sailing ship trapped in the ice. Explorers seeking the Northwest Passage. Now aboard, the Being could smell the bodies of other frozen, starved men, although the crew were not all dead, not yet. No one had noticed when he’d brazenly approached. There was no watch. What would they be watching for?

Deathwatch. Death, when it came again, would creep upon these men slowly, on little cat’s paws. He knew what it was to die by inches.

The clump of heavy boots, and then the captain of the vessel came into the cabin—the tomb—and halted. The Being was not surprised when, looking up, he saw that the captain had averted his eyes. Yes, yes, hideous to look upon. A monster, an abomination. Only a blind man had ever loved him.

The Being’s mourning wails hardened into sobs, and still the captain said nothing. The sobs became words, and the bitterness and remorse and shame torrented out of him. Yes, he had murdered Frankenstein’s innocent friends and family. Yes, Frankenstein had died a failure in his own eyes, not for making the monster but for not ending the monster. And so the Being swore he would do what Frankenstein had failed to do: he would take his own life.

The captain never spoke.

Tears froze on the Being’s dead-white skin as he hefted Frankenstein’s sled with all its contents to his ice-raft, which had conveyed him to the ship too late to lay eyes on the living Frankenstein after hundreds and thousands of miles in pursuit. He was of grim purpose now: He would leave no trace behind of his Creator, nor of himself. He gathered wood from the emptied barrels and crates around the imprisoned vessel and added those to the raft. A prodigious weight. His intention was to burn himself on a funeral pyre; but it seemed likely that before that happened, the raft would sink from its additional burdens and he would drown. By ice or by fire, he would die.

He pushed off, and the ship in its prison of ice receded. Farewell, Creator, forever farewell.

The polar sea was known to him. As the waves tossed his raft, he thought many times of falling in. How simple it would be. But he wanted obliteration, to leave no trace, and it was possible that his frozen corpse would wash up on a shore. If that happened, men would examine him, dissect him, and another ambitious scientist would use the knowledge gleaned thereby to create another monster.

Yet the sea beckoned. The waves splashed over his numb feet and soaked the heavy coat he wore more to obscure his appearance that to protect him from the elements. A human would have frozen to death by now. It was a testament to Frankenstein’s compulsion to destroy him that the man lived through journeys like this as long as he had.

I held him in my arms. I wept over him. Would he have wept, would he have mourned—

And then he heard a sound between the thrash and crash of the waves: a tiny mewing. He blinked, listening. There it was again, feeble and weak.

Un chat, he thought, French of course being his first language. A cat.

In the pocket of his ragged, useless coat.

The Being dipped his hand inside and felt the soft fur, the warmth. He drew it out. It was a tiny tiger-stripped kitten, all ears and eyes, very new to the world. How it gotten into his pocket? Ships often kept cats aboard to kill the rats; perhaps theirs had had a litter?

The kitten gazed up at him and this time only moved its mouth. It must be starving. He put it back in his pocket and rooted through Frankenstein’s belongings. Furs and some of the newly developed tinned foods—meat and pea soup. Perhaps the kitten was old enough for solid food; he had no milk to give it.

Forcing open a can of meat, he cleared a section of Frankenstein’s sled and set the kitten down. It fell upon the meat and began to devour it. The Being watched; then, as a wave lifted the raft up and up, he steadied the sled with a hand even though it was well-lashed to the raft. The cat stumbled from the force of the movement but kept eating.

The day stretched out, long and stormy. Now he fought the sea. He must reach land and give this little creature its life. He could not die until he had saved it. So he would die by fire then. On land.

Just not quite yet.

*****

The Being had led Frankenstein on a wild hunt for years, remaining just out of reach across deserts and snowy glaciers, gentle valleys and poisonous forests, drawing him along. Thus the Being knew the world well, and made land by following the stars—if land it could be called, as it was covered with ice and snow. By then, the cat had devoured a second tin of meat and spent hours in its fur bed purring and grooming itself. When they washed up on shore, the Being carried the sled to solid earth and deposited it in a small cave. The kitten slept. After he had transferred everything from his raft, he pulled that up onto land, too. He started a fire with the driest bits of wood in his cache, and ate some tinned meat as well. Exhausted, he drifted into a languorous slumber. At some point the kitten curled beneath his chin and padded its paws against his gray, wrinkled skin, and purred.

Over time, he caught fish and birds. The kitten hunted too. He named it Ange. Angel. After some weeks of sustenance and safety, he told himself that Ange could live without him now. He could build his funeral pyre. But the cat looked small, and it followed him everywhere. At night it curled up and padded his neck and chest. So he told himself one more night and then one more, and he had no idea how long they lived in the cave.

Then one morning, ship’s sails rose on the horizon. The vessel was making for land, their land. He packed everything that was left onto Frankenstein’s sled in a whirlwind of worry and beckoned Ange to take its place among the furs. Snow began to fall, covering their tracks as he pushed the sled away from the soot-blackened walls of their home.

He didn’t know if and when the ship had landed; he and the kitten were leagues away by then, safe again.

“Perhaps it would have been better for you if I had left you to them,” he said. But who could know what kind of men were aboard that ship?

*****

The trek over the snowfields dragged on, long, arduous. The Being was used to it; he had led Frankenstein a grueling chase over a dozen snowfields; he had caught rabbits for the man and cut kindling for him and performed a dozen other tasks to keep Frankenstein alive so that he could hunt him down. Why had he done it, taunted the Creator so, urged him on when he could have stepped from the shadows at any moment and snapped his fragile human neck? Could he now admit the profound exhilaration of being the sole focus of Frankenstein’s entire life? To be seen by the author of his being? Even if hated, to be seen?

One look at his child in the seconds after his revivification, and Victor Frankenstein had denied him and fled from him. To know that the sight of him in the distance, a flickering presence in the fogs, his footprint on a sandy beach, were what had kept Frankenstein alive all this time … even if driven by hate, it was for hatred of him.

Now he was the focus of someone else. Ange lounged on its furs and ate dried fish, sipped water, purred and grew as the Being conveyed it across the snowfields, across the steppes. It stretched up from the sled and licked the Being’s desiccated fingertips.

“You would do that to a log if it had rescued you,” he said aloud.

He lost track of time, but the kitten matured into a cat. Scattered, occasional dots on the landscape revealed the presence of human beings. He thought he had avoided them all until one night, as he maneuvered by moonlight into a ravine, he came across a trio of youths dressed in heavy furs who hurled spears at him, shouting in a language he didn’t understand. However, their meaning was clear: he was a beast, a monster, and they should kill him.

This was nothing new, but so much time had passed that it was a fresh shock. Well clear of their attacks, he pushed on into a copse of trees, watching as they scrambled out of sight, yelling at the tops of their lungs. They would alert their tribesmen, then.

Ange began to yowl, as if it knew something was wrong. It paced back and forth it its little den among the furs in the sled, cries rising with the wind.

“Ssh, ssh, petit Ange,” the Being said. “It’s all right.”

The cat would not be comforted, and the rising tide of distress pushed the Being to hurry, though he had no idea where he was going or if he would ever stop. He thought longingly of their cave and thought of it as home, and realized that it was the first time he had ever thought of anywhere as home.

When the rains came down, hard, Ange protested and then grew silent. The Being feared for it, pulling back layers of soaked furs to find its tiger-fur drenched in frost. The sharpest fear he had ever known stabbed through him; he picked up the limp body and gathered it against his chest, perhaps slightly warmer—he hoped so—and draped his body forward so that he created a shield from the elements. He ran through the rain, crooking his neck up as he forced the sled over rocks and newly sprung scrub. The cat did not move.

Night, day, night of rain; in the dawn, a stone hut perched like a pebble beside a swollen stream. He had no thought or hesitation except that Ange needed warmth and shelter; he guided the sled to an overhanging section of a thatched roof that had mostly tumbled in on itself and hurried to the door. He started to knock but thought better of it; one look at him and the inhabitants would never notice the little bundle in his arms.

He went to a window and peered in. There were no lights, but a flash of lightning revealed a small table and chair coated with dust and cobwebs. Deserted, then?

Emboldened, he pushed open the door, which gave way easily, and went inside. Rain poured in from several sections of the roof, but other areas of the room were dry. He made out the table he had seen through the window and laid Ange on it. He was rewarded with a tiny mew, such as Ange had made when it was a kitten.

He ran back out to the sled and hesitated but a moment before he carried everything it had contained—soaked furs, dried fish and bird flesh—then tore it apart and carried the pieces inside, laying them out like the cat to dry. Though the rain and wind washed in, he kept the front door open for the light. Another flash of lightning revealed a hearth, and in it, some half-burned logs.

He had learned to start fires by rubbing sticks together. He reached for the chair to break it apart into manageable pieces. As he did so, the rain stopped.

“Merci,” he said aloud, although to whom or what he did not know.

Eventually he discovered three pieces of flint and a pile of dusty tinder moss on the hearth, and after no small effort he set the half-burned wood alight. Once he trusted it to continue, he carefully gathered Ange up and brought it to the warmth. He studied the closed eyes, its chest, and wondered if Frankenstein had gazed at him this way, willing life into him. The man had to have looked upon him a thousand times; Frankenstein had to have seen the Being’s face and body as he put together pieces of corpses and passed current through all the fissures and stitches, welts, scars. When had wonder turned to disgust? The answer did not lie in the scientist’s journal. The pages were filled with zeal and focus—the legs, the arms, the eyeballs and teeth. Charnel houses. Graves. Had he never stopped to feel what he was doing?

“Ange, Ange,” he whispered, as if his words could conjure the breath of life. He grimaced as the smoke snaked up the chimney and wondered if it would bring investigators. Were other huts nearby? Were people?

Carefully, he gathered up the cat and brought it to the fire. He sank down on his knees and in a posture of supplication held it toward the fire. He himself was just as wet and cold and so his embrace would offer no comfort. He made sure he was not too close to the flames. The warmth penetrated his knuckles, the skin on his forehead and cheeks; he bowed his head and studied the little face, the closed eyes. What a thing was a cat. What a treasure.

When Ange open its eyes and licked his palm, tears rolled down his cheeks.

*****

The stone hut lay in close proximity to a village.

When the Being discovered that, he regretted tearing the sled apart and burning it for warmth. He had already taken large sections of the thatched roof and spread them across the floor to dry out; and torn branches off the trees as well. He could burn those to keep the cat warm. It would be difficult to rebuild the sled. He decided to fashion a simple travois and heap the furs and their good stores on it and leave as soon as possible. The plan wearied him. Though he was supposed to be immortal and endowed with superior strength, he was exhausted. Where would their meanderings take them next? Would they ever find peace?

His plan was further complicated when Ange went missing. Three days passed without sight of it. Anxiety weighed down the Being. Cats hunt, he reminded himself. It is in their nature to roam.

But he was in terror of what the villagers might do to a stray animal. During Frankenstein’s pursuit of him, he had witnessed incidents of barbarity toward animals that he had attempted to forget—along with their violence toward himself. Everywhere, Frankenstein had been hailed as a savior, a knight-errant sent off with their blessings off to kill the beast—the Being. So, yes, a kind widow or little child might put out a dish of cream for Ange, but there were others who would gleefully torment it. They would do as bad or worse to him. But he could not—would not leave without his cat.

By night, he walked in ever-expanding circles, carrying dried fish to entice Ange back to his side. When it didn’t appear, he chanced going out in daylight, moving closer and closer to the village until he entered the village itself. At night, he crept between the buildings, smelling their stews and breads, listening to their music, their conversations. They spoke a form of French and he could pick out words here and there. None of them were the word for cat.

He learned that there was another group of humans as well. They lived in round homes made of ice. He had heard their language before but had not learned any words. He had no expectation that they would treat him any better than the first group he had encountered, and so he moved in shadow as he searched for Ange.

Snows fell, and sleet; he kept his appointed rounds as he searched. Garbage and leavings littered the ground near the structures. The abundance of food might have enticed Ange. Someone might have taken Ange in. What if they turned on the cat, as Frankenstein had turned on him? He saw no other cats. These people did not seem to have pets. What if Ange was hurt?

He searched. One snowy night, he sensed a gaze upon himself and whirled around. A figure many yards away had been following the imprints of his enormous, half-shod feet in the snow, bent over with a torch in its right hand. Now it looked up and a beat too slowly, the Being hid behind the corner of a rickety wooden building. The figure turned, ran; there was a shout.

The Being fled the village and snow covered his tracks. But he was afraid to enter the hut in case he had been followed. He hid in the darkness behind an enormous rock. No one came.

He waited some time before resuming his search. The snows were less frequent; the air was warming. He didn’t know how much time had passed. He thought about leaving, about his vow to kill himself. He wanted to approach, ask, Do you have my cat? Is it safe with you? Will you give it a long life?

But he couldn’t, even if he could piece the questions together. They would never hear his cogent use of language. They would only see a demon.

*****

Now and then, he was spotted. He heard cries. Were they weaving stories about him by their firesides? Were they making plans to hunt him? One night, a rock was hurled at him.

The next night, a brown shape skulked between the houses. Large, furry, predatory. Un ours. A bear. A small cat would be but one meal: the Being ran it down, seized it, killed it. He left the carcass where it lay: I can be a friend to you. But he fear the message would more likely be I can do this to you.

The days stretched out longer, though the nights were still cold; there were fewer dark hours to conduct his search. He grew more anxious as a group of men began to patrol: they had to be looking for him. His days were numbered if he stayed.

He thought of his vow.

He fished in his river, caught fish, dried them. He trailed bits of dried fish from the village to his hut, praying Ange would track him. They were untouched. He tried again. Untouched.

He knew he had to make a decision.

That night, he took the last of his fish and returned to the village. As he crept among the familiar structure, a scream pierced the blackness.

I’ve been spotted, he thought. He turned to run, but caught a flash of brown as it sped past. He whirled on it: a large brown bear was joining its mate as it pursued a young woman in furs and a black woolen hood.

The Being yelled and waved his arms. The two bears rose up on their hind legs as the woman fell backwards, shrieking. He approached without hesitation; he shouted and picked up rocks and the bears turned from her to him.

The battle was ferocious, but only one bear fought. The other fled. The attacker slashed and bit. The Being did the same. He could feel pain and did, but in the end he prevailed. Though the bear was not yet dead, it would die. The muddy, icy earth was wet with blood from both assailants—bear and Being.

The woman’s screams had brought others, who had watched and shouted. They were not cheering his victory. They were terrified, horrified.

He raced for the hut. He could move much faster than a mob. Once he crossed the threshold, he realized that he had no need of anything inside. He had thought of this place as his, and Ange’s, as shelter, sanctuary. But that was a lie; he wasn’t meant to live anywhere.

He was about to wheel back around and leave when he heard a yowl. Another. Ange! He thudded on his large feet toward the sound.

And there she was—for she was a she; and not only that: she was becoming a mother. Two tiny bundles lay in piles of fluids, mewing with their eyes closed as Ange strained to give birth to another.

“Ange, Ange,” he said, and the cat’s eyes rolled as he looked up at him. “We must go, Ange.”

But when he reached for her, she shrank away, straining, yowling. So he bent down beside her, looming over her like a great mountain as he whispered encouragement: “You’re doing well, petite. What a beautiful mother you are.”

The third was born! She licked off the blood and birth sac. But she was not done. And he heard them. The cries of villagers. Harsh, angry, fearful. He had heard cries like that for years. Murderous.

“Vite.” Quickly, he pleaded. If only she would finish, he could gather them all up, run—

But Ange was not done.

They were outside his door now, slamming into it. Thud, thud, thud—something on the roof. Ange stared up at him and he smiled at her in reassurance.

“It’s all right,” he said softly in French. “I will protect you.”

Smoke seeped in; the thatch above him smoldered, then caught fire. There was more wood in the hut’s structure than he had realized; it started to catch. Flames sprouted and grew like vines.

On his knees, he bent forward, offering his back to the falling embers as Ange labored. Chunks of burning wood slammed against his coat, then burned through. That pain added to the injuries he had sustained in the bear fight; he grunted in agony, but did not move from his position. He felt the soft pressure of the newborn kittens as they bobbled against his forearms.

His coat was on fire. He did not move. His skin blistered. He did not move.

God is answering my prayers, he thought. God sees me. I am fulfilling my vow in the best way. I am going to die protecting my cat.

The door burst open.

But he did not know it.

*****

He awoke.

He was lying in a bed in a small room. Something was pressing down on his chest. It was Ange. She mewed at him and licked his cheek.

“Ah,” he whispered.

A rustling sound answered, and the young woman he had saved from the bear drew near. She held a cloth in her right hand and a kitten in the other. Its eyes were open. She approached timidly and pressed the cloth on his forehead. The kitten wriggled from her grasp and she leaned over to deposit it beside its mother on the Being’s chest. Ange began to knead and pad. Her movements brought pain, but they also brought such joy that the Being smiled.

The young woman petted Ange, then smiled at him. She picked up a clay drinking vessel and raised her eyebrows: Would you like to drink? His hands were bandaged. She brought the vessel to his lips.

She pointed to herself and asked a question. When he made no reply, she said, “Anne.” She pointed back at him. Perhaps she said, “Vous?” which meant “You?”

He had never had a name. He was quiet for a long time, what was to him a lifetime. I want to tell you, he thought, that I have done terrible things. I took innocent lives. I killed my Creator as surely as if I had wrung his neck like a chicken.

She put her arm around his massive shoulders and urged him to sit up. Then she pointed downward and he peered over the bed. On the floor in a basket lined with furs, Ange’s kittens tumbled and played.

She pointed at him: You did this. She said again, “Anne.”

Tears flowed: a baptism.

And he said, “I am Père des Chats.”

Father of Cats.