The December Second Selected Story is by

Tim Jeffreys

Please feel free to email Tim at: timdazjef@yahoo.co.uk

THE FROZEN MILL POND

by Tim Jeffreys

Pulling on his coat, ten-year-old Liam slipped out of the back door of the house and ran as fast as he could down the lawn with his hands pressed over his ears. It was a mid-January morning, a Sunday. Christmas was over—for Liam at least—and forgotten.

The sun was shining, but the air was sharp with cold, the grass laced with frost and it was stiff underfoot. At the end of the garden, he was forced to remove his hands from his head in order to push aside the loose board in the fence.

With his ears uncovered, he could hear again his parents’ warring shouts. He hesitated a moment, breathing hard and listening, noticing how his breath clouded on the air. Then, with no sign that the argument was coming to an end, he scrabbled through the hole in the fence.

Behind the house was a dense spinney of trees through which he’d traveled enough to make a path down the short steep slope to the banks of the old mill pond. It was where he went to hide when his parents were fighting. He would sit by the bank in the hollow of a tree root and stare at the water. The surface of the pond was so calm that it made him feel peaceful and he could forget about the fighting from which he always fled.

In time, after the argument was over, his mother would realize he was missing and shout for him from the back door. He would idle home then and she would put her hand on his head and say: Come on then, son, get in…and the house would be quiet and they would all pretend nothing had happened.

Today, when he emerged from the trees and saw the pond, he drew a sharp breath and stared. The surface of the pond was completely frozen over.

Liam beat his hands together and laughed. He examined the ice. It was clear enough, mostly, to see the murky water underneath and it looked thick. He hunted around for a large stone and dumped it with as much strength as he could muster onto the ice. He laughed again to see the stone bounce and skitter along the frozen pond.

The ice was thick! Perhaps, he thought excitedly, it’s even thick enough to walk on.

His mother’s voice crept into the back of his mind, something she always told him: Don’t you even think about setting foot on that ice, young man! I’ll beat your brains out if you do!

Remembering his mother, his looked over his shoulder and listened hard to see if he could still hear voices from the house. He thought he could hear them, dimly. So it was not over yet. It would be a while still before his mother realized he had ducked out of the door.

He moved one foot forward and placed it on the ice. Slowly, he lowered his weight onto that one foot, keeping his ears tuned for any sounds of breaking ice.

There were no sounds. The ice supported the weight he had placed on that one foot. With great care, laughing nervously under his breath, he lifted his other foot and placed that one on the ice, too. He was prepared to leap back on to the bank if he saw the ice breaking under him, but it didn’t break.

He was standing on the surface. He lifted his gaze and looked at the far bank. On that side there was a wooden jetty and a rope swing tied in the trees. He had always wanted to try the rope swing but until now he had never found a way to cross the pond. The trees and bushes were too dense on either side for him to walk around to the other side. He had thought often, when he sat here waiting for his parents’ arguments to end, about making some kind of boat or raft. Now though, he didn’t need to.

He could just walk to the other side, couldn’t he? Across the ice.

He thought about it for a long moment as he stood on the surface of the frozen pond, rubbing his hands together against the cold. Routing in his coat pockets, he found the wool mittens his grandmother had knitted for him—the ones he was usually too embarrassed to wear—and slipped them on.

At last, he decided that since the ice still hadn’t shown any signs of cracking, it would be safe to cross to the other side. He began by shuffling his feet forward. Then, as he grew braver, he began to lift them and place them in front of him. About half way across the pond, he decided there was nothing whatsoever to worry about—the surface of the water was frozen solid—and he marched the remaining distance across the ice, laughing.

He did it! He reached the other side of the pond, and scrambled up onto the jetty.

He found then that the rope swing was caught too high in the trees for him to reach it. He walked to the other end of the jetty, looking for a long stick or something similar he could use to unhook the swing.

But at the farthest end of the jetty, he noticed that the ice was cracking as it came up against the bank. It was thinner there.

Deciding to test it, and looked around for a large stone. He soon found one, larger even that the one he’d thrown at the ice on the other bank, and struggled with it to the far end of the jetty. There he stood and, exerting himself, lifted the stone above his head. He tipped forward and let the stone fall, expecting it to bounce on the ice.

Instead the stone crashed straight through the ice with a crunching sound and a leap of water. Liam stood for a moment, examining the hole in the ice.

The water inside the hole was dark, almost black. As he stared at, his brow knit. Just for a moment, it looked like a face had appeared in the hole. The face was dark, almost as dark as the water surrounding it, but it was almost the face of a man except that the glowering mouth was full of sharp little teeth and the eyes were orange-colored and alive with outrage.

Liam blinked, and when he looked again the face was gone. He drew back a little from the edge of the jetty, still staring at the hole in the ice. It was now just a rough circle of dark water.

I shouldn’t have done that, he thought. I shouldn’t have broken the ice.

Then he thought: What did I just see?

Various possibilities occurred to him. He knew it hadn’t been a fish, unless it was some monstrous fish that had grown fat and mutated on chemical waste (he’d read about similar things in his comic books). Perhaps it had been a seal. But a seal, in a mill pond? Anyway, it hadn’t looked like a seal, it had looked like some kind of…

…of…

…monster.

No, he decided then, casting a look back at the hole, it was nothing. I imagined it, that’s all. There was nothing there. There’s nothing in this pond except maybe some stickleback fish.

Nevertheless he shivered.

Just then, he heard his mother shouting his name. It was time to go home. He ran along the jetty to the place where he’d first stepped up on to it, but before he climbed down onto the ice he paused.

What if he hadn’t imagined it? What if there was something down there, under the ice? Something that wanted to get him? How could he go back across the pond?

His mother called his name insistently. He shouted back, but she went on calling as if she hadn’t heard.

He was going to have to walk back over the ice.

He sat down on the jetty and lowered himself carefully onto the frozen surface. He began to shuffle forward, staring down at his feet as he did.

After a few paces, he stopped, thinking he saw something moving in the water beneath the ice. He felt his heart beat faster in his chest. He mother’s voice went on calling.

“Here!” he shouted back. “I’m here! I’m coming!”

He began to move forward, but then he drew a sharp breath and stopped.

He thought he’d felt a small shudder in the ice under his feet, as if something had struck against it from below. He looked down, and thought he saw something moving across the underside of the ice.

It was difficult to tell. Everything was so dark down there, and the ice had patches of frost on its surface, but he was sure he’d seen something glide along under his feet. He remembered again the face he thought he’d seen in the hole. That furious gaze, those sharp little teeth. He thought madly: Fish? Not a fish! Too big! Not a seal! No seals here! It’s something else! Something…

There was another shudder in the ice underneath him, unmistakable this time.

“I’m here!” he shouted again to his mother in desperation. “Here on the pond!”

The ice under him shuddered again. With a jolt of fear, he leapt forward and ran a few paces across the ice until with a great horrifying cracking sound it broke under him. He went down.

The shock of the cold cut his scream short. Only his legs had gone into the water. The top half of his body was still on the ice, but the pain was like knives.

Panicked, horrified, drawing sharp little breaths and thinking of that thing down there in the water, he began to frantically scrabble and claw at the ice, trying to drag his legs out of the water. He realized with horror that more ice was breaking under his weight. He tried to shout but was able only to make a breathy sound. Somehow in his horror and panic, he remembered that in situations like this you had to spread your weight. He had seen that on the TV or read it somewhere, you had to spread your weight out on the ice. He tried to do this, clawing with his mittened fingers for purchase.

He froze with fear when he saw, right in front of his face, a dark form pass in the water under the ice. There was no denying it now. There was something down there, something in the water. It wants to get me! It wants to get me because I broke the ice! I should never have broken the ice!

With renewed vigor and mounting panic, he kicked and heaved and clawed and slithered and at last managed to drag his legs back onto the surface of the ice. He was out!

He lay still on top of the ice, gasping for air.

He remained spread-eagled on the ice for some moments, drawing breath in little gasps and wondering what he should do next. He legs were numb with cold and he was shivering. His teeth chattered uncontrollably. He thought that he might die if he didn’t do something, get up, but he was afraid to move.

He could still hear his mother calling his name. Perhaps she thought he had run away. Perhaps she thought that this time they had driven him away, with their quarrelling and their door slamming. It was always as if a storm had erupted in the house. Often it came from nowhere, with no warning. And though he hated it when his parents fought, it was the aftermath he hated most, when he went back home and all was quiet and there was a tension in the air, like the tension before a storm, as if another argument might break out if anyone spoke, and Liam knew he had to be very quiet and do as he was told so as not to start them off again.

He thought about telling his parents that there was a monster in the mill pond at the end of their garden. Would they believe him? It’s under the surface, he would tell them. Under the ice. I saw it. It looked at me. It was angry. He tried again to shout for his mother but only a thin reedy sound emerged from his throat.

After a few moments, he found the courage to look back towards the hole his legs had made in the ice, expecting to see something rearing up out of the water, reaching for him, but there was nothing there. Now, despite the pain in his legs and the fear that paralyzed him and the fact that he could hardly draw breath, he realized he had to move.

Half sobbing, feeling weak and numb with cold, he raised himself on hands and knees and decided he would crawl to safety. That would help keep his weight spread out. But then, when he tried to move forward, he realized he couldn’t. His leg was caught.

Looking behind him, he saw that something long and thin and black was emerging out of the hole in the ice and had coiled itself around his ankle. A tentacle, he thought. It’s a tentacle. It’s that…no, no…it’s that…

He didn’t have time to finish the thought. He was yanked suddenly backwards.

He flailed his arms and clutched at the ice and screamed, finding his voice at last, but that too was cut short as he was dragged backwards into the ice hole. There was a struggle and a spray of water, then Liam was gone. Within a few seconds, all was still. A single woolen mitten remained alone upon the ice.

*****

His mother, at the back door of the house, fell silent a moment and cocked her head to the side, thinking she’d heard something.

From behind came her husband’s voice. “What the hell are you doing? Get in or get out, it’s freezing cold in here.”

“I’m trying to get Liam in,” she said sharply, half turning. “He’s run off again because of you.”

“Me? You started it. What did I do?”

“You know what you did!”

Ignoring him as he went on, she faced forward again and began calling in a loud impatient voice, full of annoyance: “Liam! Liam! Liam?”

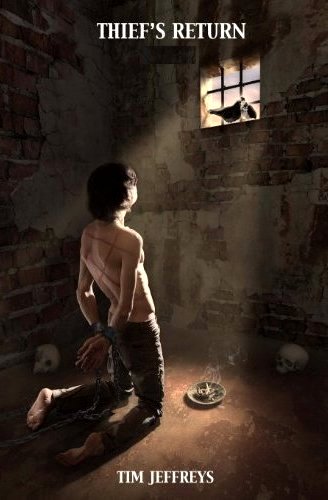

Tim Jeffreys is the author of five collections of short stories, the most recent being The Lucky Penny & Other Stories, as well as the first two books of his Thief saga. His short fiction has appeared in various anthologies and magazines. His stories are best described as a mix of horror, fairytale, black comedy, and everyday life.

Originally from Manchester, UK, Tim now lives in the south west of England where he can be found either working at his day job, taking care of his daughter, haunting libraries, or sitting at his desk writing.

Visit him online at www.timjeffreyswriter.webs.com.