The April Editor's Pick Story is by Daniel Davis

Please feel free to email Daniel at: dwdavis86@gmail.com

THE CREEPING

by Daniel Davis

Leaves blowing across the back porch. That’s all it was.

Or so Lindsay tried telling herself.

It made sense. About twenty feet from the back door, the forest began: a five-mile stretch of wilderness pitted with ravines and dry creek beds. In the autumn, they had leaves everywhere. You couldn’t keep them out of the house.

Besides, she was turning fourteen in three weeks. She was just a bit too old to believe that the rustling sound could be…something else.

She blamed her father. With Halloween just weeks away, he’d been watching horror movies every night, despite protests from Lindsay and her mother.

Last night it had been Night of the Living Dead, the black and white one, so at least it wasn’t too gory. But hearing the shuffling sounds of zombies coming through the walls had been enough to set Lindsay on edge.

It was just a dream, and those are just leaves. There aren’t zombies out there.

Of course not. But there could be other things. A coyote, for example. Or a prowler. Someone who knew that inside was a girl who was spending her first night alone in the house, that after almost fourteen years her parents had finally decided she was old enough not to swallow Drano by mistake or get electrocuted while taking a shower.

Her parents had gone on an extended date night, and for once Lindsay didn’t have to suffer through their forced flirting. Grownups acting like they were teenagers. Jesus. Lindsay winced at the image, and for a moment her fear went away.

It came back when the sound returned.

She couldn’t quite bring herself to press her face to the sliding glass door. Stupid, childish, silly…call it what you want, she just couldn’t do it. Nothing to see there anyways, idiot. Yeah. Right.

She turned her back to the door, which somehow felt worse, and tried not to think about the fact that she walked out of the kitchen more quickly than was required. Back in the living room, the TV was tuned to Comedy Central, the roast of someone Lindsay had never heard of. But that was okay, because it was still funny. You didn’t have to know someone to find it amusing when they were insulted. You just laughed anyways.

She sat in her father’s recliner, curled up in his blanket. It smelled of him. Lindsay remembered how he’d always seemed so big when she was younger, how she’d always known he could protect her from anything. In reality, he was short and squat, kind of funny looking. But yes, he could protect her. When he was around.

The show went to commercials, and in the brief silence before the programming change, Lindsay heard the rustling again. This time from outside the front door.

“It’s windy,” she told the door. “It’s really windy, and there are a lot of leaves.”

Both true. But that answer wasn’t satisfying.

Ridiculous. She glanced at the clock: 9:07 PM. Her parents wouldn’t be back for fifty-three minutes. Well, probably more like forty-five, depending on when the movie got out. What had they gone to see? A romantic comedy, something short? Or one of mother’s brooding dramas, which typically ran over two hours? And they’d gone to Olive Garden, and…oh crap…the nearest Olive Garden was an hour away. When had they left? They wouldn’t be back at ten; they’d be back at eleven. Oh no.

“Stupid!” It burst out, perhaps the angriest word Lindsay had ever uttered. She’d never been so mad at herself. Her first night alone and here she was proving that her parents had always been right, that she couldn’t be left by herself.

“The hell I can’t,” she said, trying out a word worse than stupid. She threw the blanket onto the floor and hopped out of the recliner without even lowering the leg rest. She didn’t have to open the front door. She didn’t have to go that far. Next to the door was the switch for the porch light. Then she could go to the window, pull back the blinds, and look out at the nothing that was on the porch.

That’s exactly what she did, except at the window she hesitated, the little girl inside of her screaming Don’t do it, don’t do it! Lindsay told herself to shut up, and opened the blinds.

She screamed.

Her porch was gone.

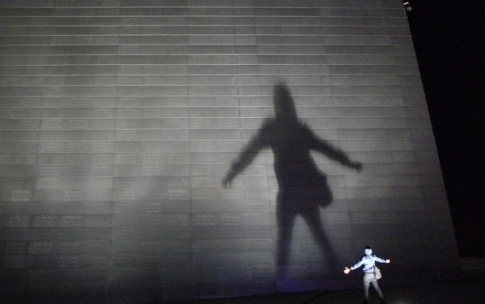

Where there should have been cement, there was nothing but black, the deepest, darkest black that Lindsay had ever seen, the kind that black holes are made out of, the kind that sucks up everything, every trace of light that reaches it.

And it was moving.

The rustling sound came from the blackness sliding against the house, a soft grating sound that did sound like leaves. The black puddle—it was so much bigger than that, but she couldn't think of any other word for it—moved slowly, like how molasses moved.

Was it a liquid, though? Despite herself, Lindsay found her face pressed against the window, eyes squinting. No. It seemed too thick to be a liquid. And the wind wasn’t blowing it—there were no ripples on its surface, like on a pond during a strong breeze. The blackness shifted, yes, but the movements seemed deliberate, as though it were trying to get into the house.

The thought chilled her. And then she remembered: if the sounds were coming from the back porch as well…

She raced to the backdoor and turned on the porch light. Her back porch was covered as well. Most of the yard looked that way too. The forest was still there, as far as she could see, but she had no doubt that the puddle was there as well, winding its way through the trees. She could feel it, the way you can sense being watched. Yes, it was back there. It stretched into the forest…and beyond.

Lindsay grabbed her cell phone and speed-dialed her father’s number. Her heart froze when her call went straight to voicemail.

Of course; he always turned his phone off when he was at a movie. But her mother wouldn’t, not with Lindsay home alone, and that’s the next number Lindsay dialed. She listened to the classical score, waiting for her mother to pick up.

Come on, come on…

Voicemail. She couldn’t believe it.

Lindsay pulled the phone away from her ear, staring at the screen. A snapshot of her mother, taken the year before, stared back at her, smiling, almost taunting her. Why wasn’t her mother answering?

She went to the fridge and found her next-door neighbor’s number. Mr. Anderson was old and still had a landline, probably the only person on the block. But even old Mr. Anderson didn’t answer. Of course his was the only neighbor’s number her parents had.

Next, she tried 911. She felt foolish doing it, even though she had a legitimate reason. But perhaps this was a dream, or she was hallucinating, and when the cops got here they’d show her that nothing was wrong, there was just been something wrong with the fish she had for dinner—

Busy signal. How could Emergency Services have a busy signal?

That was it. Lindsay threw the phone onto the counter and listened to her screen crack, but she didn’t care. If 911 wouldn’t answer, no one would, so her phone was useless with or without a cracked screen.

This was big. This was huge. She thought of the movies her father had made her watch. In all of them, when 911 was busy, that meant it wasn’t a local thing, but regional, maybe even national.

It meant things were bad.

So what could she do? The doors were obviously out of the question; the house was surrounded. She glanced at the garage door. She’d never driven before, but she’d watched her parents do it often enough. Didn’t seem that hard. And honestly, if she wrecked the car…well, there were bigger issues right now.

She grabbed the keys off the rack. I can’t let anyone see me driving a Prius, she thought, wishing her parents had left the Range Rover behind. Then she laughed at the absurdity of it, and opened the garage door.

And saw it.

She didn’t scream this time. She was caught mid-laugh, so all that came out was a faint hiss, like she was choking to death. Inches from her feet, where the step down should have been, there was nothing but darkness.

It had gotten into the garage.

She stepped back involuntarily, had a moment to think, I should have closed the door, and then the black puddle slipped into the house.

She stood transfixed, watching it inch across the linoleum kitchen floor. It seemed to suck up everything it touched; you couldn't tell that there was a floor beneath it. It looked a hundred feet deep, a million. Up close, it did seem to be a liquid of some sort, a kind of thick, living oil. An invading ocean from outer space…or Hell.

Lindsay blinked. She had to move. She had to go. But where? She took a step back, bumping into the counter. She couldn’t get out of the house, no. So she couldn’t escape. But she could get to high ground at least, to the attic, and wait things out.

Or…

She reached behind her, opened a drawer, and pulled out a book of matches. She smiled and laughed, flipping off the puddle. “Take this,” she said, pulling out a match. She struck it, then tossed the flame into the liquid.

For a second, hope flared—the flame grew brighter, and she thought the blackness would catch fire; maybe it was like gasoline or something. But then the flame sputtered and died, and the match disappeared.

So much for Plan B.

She ran out of the kitchen and into the hallway. She took a moment to glance into the living room, drawn by the flashing of the television screen. She wasn’t at all surprised to see that the puddle had somehow made its way under the front door—of course that would happen. It had managed to cross the entire living room, seeping into the hall, like it knew where she was…like it had been planning on ambushing her, trapping her in the kitchen.

Lindsay wrenched her eyes away from the puddle and darted down the hall. She could hear it behind her, growing closer, knowing it had her trapped in the house. She couldn’t get out, but she could go up; climb high enough it couldn’t touch her, wait for someone to come along and get rid of this thing.

But what if no one ever came?

The thought froze her. Of course someone was coming; she couldn’t let herself think about the alternative. Those kind of thoughts were hopeless and they would only make her despair. Right now, she needed to be positive; she needed to hope.

She also needed to be smart, and not like those dumb women in the horror movies. She stood with her arm outstretched, fingers inches away from the door to the attic. She could pull it down, scramble up, and hide. And wait for someone to come, however long that took. If they were coming at all.

Or she could do something else.

Like what? You have any brilliant ideas?

Actually, she did. Something scratching away at the back of her memory, something so mundane that she normally ignored it, the way you never stop to think about breathing or moving your legs.

The thought wasn’t entirely formed yet, but she had to do something now, so she abandoned the attic and instead ran to the end of the hall. She darted into her bedroom, slamming the door shut behind her.

“What are you doing?” she asked herself in the darkness.

So she didn’t know exactly what her intentions were, but that was okay. She let her gut guide her; right now, her instincts told her to open the window. It hit her, then, or at least part of it: if she climbed into the attic, where there were no windows, she would be trapped. But if she climbed the terrace up to the roof…

Would it hold her? She hadn't climbed it since she was ten. In her mind, she could already feel the wood cracking beneath her weight, sending her plunging to the ground…

Well, only one way to find out.

She opened the window and glanced down. The blackness had risen; it was already halfway up to the window. She thought this was what it must be like to live next to the Mississippi every spring, watching the waters rise, knowing there was nothing you could do to stop it.

Except that's not water. Whatever it is, it’s alive.

The terrace ran right alongside her window. She’d never really understood why a one-story house needed a terrace, but she was grateful now. This far into autumn, the vines that crept up it had begun to die away, turning hard and brittle. When Lindsay reached out and grabbed the terrace, a vine crunched beneath her grip, and for a moment she thought it was the wood.

You’re crazy, girl. You’re really, really crazy.

The whole situation was crazy. A little more insanity wouldn’t change anything.

As she swung out and over the yard, she sensed the black puddle straining up to grab her. She glanced down; the surface rippled, as though sensing her passage, but the liquid hadn’t reached out for her.

So it had its limitations; that was good to know. She couldn’t set it afire, but if she could stay above it, she could remain out of its reach. Which was exactly what she intended to do, for as long as she could do it.

She climbed. The terrace didn’t break, though a few times she sensed it straining against the side of the house. She wasn't heavy by any means—her father kept suggesting she could put on a few pounds, as though she would ever consider that—but she wasn’t a child anymore. She purposely slowed her ascent, suppressing the panic she felt whenever her imagination pictured the rustling blackness below her. If she went too quickly, she’d put too much stress on the supports. She had to move as though she were walking across thing ice—which of course she wasn’t stupid enough to ever do.

After what seemed like hours, though it was probably only a minute or so, she reached the roof. She felt such relief when she swung her legs up that she took a moment to lie down, staring at the starless sky. God, what she wouldn’t do for a full moon, gentle blue moonlight falling across the…well, there was nothing for it to fall across anymore, was there? Maybe a moonless sky was for the best.

She sat up; if she lay there long enough, the adrenaline rush would fade, and she’d become too exhausted to move. She had to milk this energy for everything it was worth.

She glanced to the left, across the expanse of the roof. The Stewarts lived over there. They had a taller house, but there was also a good thirty feet separating the two buildings, and no way to cross that expanse without setting food on the ground.

The Stewart house was too far. So Lindsey turned to her right where, just a few feet away, her roof ended. About five feet beyond that was the roof to Mr. Anderson’s house.

Oh no you don’t. Who do you think you are, Bruce Willis?

Maybe not. But if she just stayed here, it'd be the same as being trapped in the attic, wouldn’t it? The liquid would rise, and if help didn’t come, she’d be stranded.

“Well,” she said, “I have no choice.”

She backed up, making sure she had a running start. When she took off, she found herself grinning at the foolishness of the idea. She wasn’t into track; she kind of liked soccer, and was maybe thinking about trying out next year, just so she’d have something to keep her occupied. But soccer wasn’t an extreme sport; it didn’t require bounding around like Superman. She needed a rifle slung across her shoulder; a bandolier full of grenades crisscrossing her chest, a cigar clenched between her teeth, and a bandana around her forehead.

The edge of the roof almost caught her by surprise. “Hey!” she screamed, snapping herself out of her reverie, and at the very last moment she launched herself into space, using every muscle in her calves and thighs, putting all of her strength into it.

If I get out of this, I’m trying out for the Olympics.

She flew too quickly for the sense of weightlessness to take hold, but her imagination felt it anyway. Her stomach dropped, her bladder threatened to let loose, and all of the blood drained from her face as she felt herself falling. She could already feel the liquid sliding up her legs, warm and thick, moving with the fervor of something alive, something hungry, ravenous—

When her feet made contact with Mr. Anderson’s roof, she screamed in fear. When her knees buckled and she fell on her face, she cried out in terror. Then, when she realized she wasn’t drowning in the blackness or being eaten alive, she pumped her fist in the air and laughed.

She made it. She’d cleared the edge of the roof by a good two feet.

“I did it,” she hissed, panting. She wondered if Mr. Anderson were below her, and what he would’ve thought.

Then she wondered if he was still alive, and pushed those thoughts from her head. Part of her wanted to check on him, but the truth was, she had no idea how to get into his house. And frankly, the best way she could help him, if he were still alive, was to get help. Sure, she was some wondrous fourteen-year-old girl who could leap tall buildings in a single bound, but she was no match for whatever the hell that black flood was.

Flood. No longer a puddle but a flood.

She moved carefully across Mr. Anderson’s roof, not being entirely sure what a rooftop was really like. Fairly smooth, she discovered, though the slight tilt to the right made her feel slightly off-balance.

She stubbed her toe a few times on the shingles, being thankful that she’d been wearing her newer, harder slippers, and not the soft flimsy ones. These things were practically shoes; it was as though the designers had intended them to be all-purpose, for whenever you suddenly discovered you had to run for your life.

This would make a hell of a commercial. I’ll pitch the idea some day; screw the Olympics, I’m going into advertising. Providing of course, I survive this.

She reached the far edge of the roof. The house beyond was also close and, like most of the homes in the neighborhood, single-story. She had always missed the two-story home that she’d lived in until she was seven, but now she was grateful at her new neighborhood’s lack of imagination.

It wasn’t until she stood at the edge of the roof that she realized what had prompted her to climb out the window in the first place…that little mundane nugget that had been on the tip of her tongue, taunting her.

The house on the other side of Mr. Anderson’s belonged to the Smiths. Mr. Smith was about as country as you could get; he wore camouflage practically everywhere, he hunted, he loved NASCAR, and he fished. He drove a beat-up Chevy Silverado, probably as old as Lindsay, which he always kept out in his driveway, no matter the time of the year.

Attached to the back of Mr. Smith’s pickup was a small trailer.

On that small trailer, never fail, winter and summer, was his fishing boat.

He’d called it a “dinghy” when he’d told Lindsay about it a few years before, and she’d laughed at the terminology. It was small, operated by a motor attached to the back.

“But,” Mr. Smith had said, winking at her, “whenever the missus complains that I’m puttin’ on a few extra pounds, I take this motor right off and just use the paddles. You can get the tricky fish that way, follow them into the shallow coves that most other boats can’t reach.” He’d tapped his forehead. “Never underestimate a hungry redneck, darlin’.”

Yeah, well, you also shouldn’t underestimate a fourteen-year-old girl driven by fear of the unimaginable.

Encouraged by her last flight through midair, Lindsay made this second jump with less trepidation, though her mind still tried convincing her that she was in free fall. She landed on her feet, maintaining her balance, and moved gracefully to the garage, where she stood triumphantly over the Silverado.

“Take that,” she told the black expanse below her.

She hopped down from the garage onto the hood of the truck, wincing as the metal dented beneath her. She figured Mr. Smith, if he were still alive, would forgive her. This was a matter of life and death, after all.

She saw that the flood had already risen almost to the height of the tires. She stared at it for a moment, enthralled, trying to imagine if it was really only a few feet deep, or if it had consumed the ground beneath it, so that it was in fact bottomless. Small waves rippled across it, forming repeating circular patterns that spread forever outward…

Lindsay wrenched her gaze away. Jesus. It was like the thing was hypnotizing her.

That did it. She climbed up over the cab of the truck and into the bed. Then she moved carefully to the trailer. She wasn't entirely sure how it worked; the liquid had risen to the base of the trailer, but she knew she didn’t have to get underneath it to drop down the rear gate. Well, she didn’t know, per say, but it made sense.

She found where the boat was tied to the trailer, and easily undid the straps, letting them fall back into the blackness. The engine was surprisingly easy to take off, though surprisingly heavy; it fell to the bottom of the boat with a dull thud, almost hitting her feet. She didn’t bother hauling it out; it might come in handy later.

She studied the rear gate. She eventually found two latches, one on either side. She had to flip a switch one way, then a second switch another. She reached down to do the one on the left, purposely focusing on her hand, not the liquid. The last thing she wanted was to become hypnotized and fall overboard.

The switch wouldn’t turn at first, and she leaned forward, putting her weight into it, grabbing the side of the boat with her other hand to stabilize herself. She grunted, straining against whatever rust or dirt held the latch in place. “Come on,” she hissed between clenched teeth. “Dammit, move!”

The latch snapped forward suddenly, and Lindsay went with it. Not far, but her hand brushed past the edge of the trailer and down into the wet darkness.

At first, there was nothing. She didn’t even know what had happened—her hand felt exactly the same, cool and dry.

But then a warmth began to set in, and it slowly escalated to the stinging burn of a bee sting. Lindsay gasped and pulled her hand back—

Except something held her hand.

She could feel the grip slowly coiling around her wrist, something both solid and pliable, powerful, like an octopus tentacle made of Jell-O. She grunted as the thing tugged downward, driving her abdomen into the side of the dinghy.

She pulled back, and felt the resistance give a little—perhaps whatever held her was only about as strong as she was, or else she’d caught it by surprise.

Fight, fight, fight!

She pulled her hand back again, but this time the thing held firm, and gave a sharp tug of its own. Again, she slammed into the boat, as if that was what the thing wanted—to beat the strength out of her, to make her weak enough to haul overboard.

The burning in her hand increased. She could imagine her flesh melting off, leaving nothing but bone. She now had a skeleton hand, and still it burned. This wasn’t water, this was acid, some corrosive living material that was purposely trying to draw her deeper into it. Maybe that’s how it fed—dissolved the flesh, sucked you dry like some sort of parasite.

The image was too much to bear. She closed her eyes and twisted her body sharply to the right. Her hand almost came out of the water—she couldn’t see it, but she could feel it. The thing below immediately pulled her back, but her near-success gave her a surge of hope, and Lindsay pulled again, a quick jerk, like playing with a fish on a line. Her father’s words, forgotten years before, came back to her: Wear it down, jerk it around a little, play with it; you’re stronger, you can outlast it.

She didn’t know if the same thing applied to intelligent liquids, but she figured it couldn’t hurt.

The thing pulled again. It wasn’t playing—its intentions were clear. So she gave a short, half-hearted tug, what her father had called a feint. The thing in the water responded in kind—pulling not quite as hard, as though convinced she were weakening. So Lindsay bit her tongue, tasting blood, and screamed, “Let me go!”

On the final word, she threw herself backwards with all her might, pushing against the floor of the boat. Her hand came out of the water, and for a brief moment, no longer than the blink of an eye, something else came with it—something darker than night, colorless yet moving, curled around her wrist and clenching tighter, squeezing, pulsating.

Then the thing let go soundlessly but quickly, clearly in pain of some sort, and plunged back beneath the surface just as Lindsay landed on the opposite side of the dinghy, the edge catching her in the small of the back.

She laid on the floor of the boat, staring at the sky, trying to catch her breath, her thoughts, her sanity. Distantly, she held her up arm; her hand was still there, skin and all. The burning sensation was fading gradually, like a bad dream, leaving behind a fuzzy numbness. She could deal with that. She could pretty much deal with anything now.

After she was convinced the thing in the black flood wasn’t going to jump aboard with her, she got up and used one of the paddles to finish undoing the latches. Then she pressed the end of the paddle against the pickup's rear windshield and pushed. The dingy screeched against the trailer; she wondered what kind of damage she was doing to the underside of the boat. However, since she didn’t see any holes, she figured it couldn’t be too bad, and proceeded until the rear end of the boat hit the liquid. Then she used the trailer itself for leverage, and after a few minutes’ struggle, the boat was floating atop the blackness.

She sat down and tentatively put the paddle into the liquid. Nothing tried to take it from her; perhaps whatever was down there only went after living material. Or maybe it just hadn’t yet figured out what this piece of plastic was for.

Lindsay had never rowed before, but she got the hang of it quickly. First, she stuck the paddle down as far as she dared, trying to touch bottom of the liquid. She wasn’t surprised to find that she couldn’t.

The paddle wasn’t very long, of course, but during her efforts to get the boat off the trailer, the flood has risen a good foot and a half. She rowed carefully, slowly, trying not to exert her already cramped muscles. She was amazed that she still had the strength for this, but she figured it was only a matter of time before her body gave in.

As she rowed, she passed houses that became steadily smaller, sucked into the liquid, until only the roofs were visible. She saw few signs of life. A couple of birds, but no people, no dogs or cats.

There was a small current atop the liquid, flowing north, against gravity. Lindsay was grateful; her parents had gone north, and that’s where she intended to go. She wanted to find her parents.

She continued to row until the action became an unconscious one, just another extension of life, like breathing. Soon the houses had vanished, and still she drifted on, heading northward, towards the city where her parents had gone.

As long as she could stay on top of the black liquid, she knew she would stay alive. She would show her parents that she could, at almost fourteen, take care of herself.

Daniel Davis is the Nonfiction Editor for The Prompt Literary Magazine. His own work has appeared in various online and print journals.

You can find him at www.dumpsterchickenmusic.blogspot.com, or on Facebook.